Celebrating Labor: The Biblical Principles behind Labor Day

As September approaches, people start looking forward to the unofficial last holiday of summer: Labor Day. Many Americans celebrate with picnics and parades—like the first one on September 5, 1882. Planned by the Central Labor Union in New York City, nearly 10,000 workers took unpaid time off to march from City Hall to Union Square, commencing the first Labor Day parade. But what prompted this parade and what was the Bible’s role in this holiday?

Labor activists first put forward the concept of a federal holiday to celebrate “the strength and esprit de corps of the trade and labor organizations” in the late 1800s. Although times had changed and agriculture was giving way to a more industrial economy, there was still an imbalance of power. At the height of the Industrial Revolution in the US, the very poor and immigrants worked in the most unsafe conditions, with little sanitary facilities, fresh air, or even occasional breaks. The average American worked 12-hour days and 7-day weeks to survive. Despite restrictions in some states, children as young as five or six worked in mills, factories, and mines, and received lower wages than adults.

Labor unions had begun to form in the mid-nineteenth century to protest these conditions, and only grew more prominent and vocal as time went on. As manufacturing became a main source of American employment, these groups leveraged their position as workers and began organizing strikes and rallies to protest conditions and demand better hours and pay. It was the beginning of a shift in power within the workforce to protect laborers from exploitation and unsafe practices imposed by their powerful employers. Protections like these were not new. In fact, the Bible refers to several of them.

In Jeremiah 22:13, it says, “Woe to him who builds his house by unrighteousness, and his upper rooms by injustice, who makes his neighbor serve him for nothing and does not give him his wages” (ESV). In the New Testament, James 5:4 says, “Behold, the wages of the laborers who mowed your fields, which you kept back by fraud, are crying out against you, and the cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord of hosts” (ESV). These biblical passages emphasize the idea of treating workers fairly, and these principles came into play in the fight for American workers’ rights in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

By 1894, 23 states had adopted the holiday, just over half the states in the Union at that time. Early that year, Congress passed an act making Labor Day a legal holiday in the District of Columbia and the territories. A few months later, on June 28, President Grover Cleveland signed the holiday into law in the hope it might repair ties with American workers. All this happened because of the upheaval in the workplace.

Even after Labor Day was made a federal holiday, many continued to fight for the rights of the poor and marginalized. One such group was the Catholic Worker Movement, established by people inspired by the teachings of Jesus, particularly the Sermon on the Mount, and the instruction of the Catholic Church, especially the Seven Works of Mercy. The group’s goal was to form a “new society within the shell of the old, a society in which it will be easier to be good. A society with no place for economic exploitation or war, for racial, gender, or religious discrimination, but would be marked by a cooperative social order without extremes of wealth and poverty and a nonviolent approach to legitimate defense and conflict resolution.” This goal, informed by biblical teachings and principles, would be met through several enterprises.

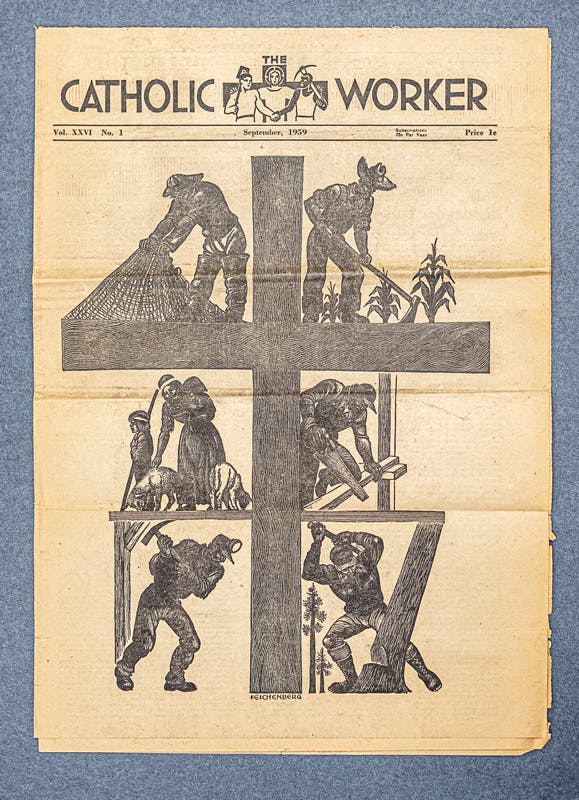

One of the most prominent was the publication of the movement’s newspaper, The Catholic Worker, to make people aware of instances of social injustice. Published by the co-founders of the Catholic Worker Movement, an undocumented immigrant and French worker-scholar, Peter Maurin, and a veteran left-wing journalist and Catholic convert, Dorothy Day, the first issue came out in May 1933. First sold in New York City for a penny a copy, it’s still published seven times a year and still only costs a penny an issue plus shipping. According to Day, its goal was, in a play on James 1:9–11, to “comfort the afflicted and to afflict the comfortable.”

Figure 1: The Catholic Worker was founded in 1933 and was edited by Dorothy Day until her death in 1980. The Catholic Worker newspaper continues to print seven issues a year for the same price as 90 years ago—1 cent per issue.

Day and Maurin attracted intellectuals and ordinary people to respond to this Catholic vision of social and personal transformation. For her part, Day used her skills as a writer to inform readers of the conditions of the poor, workers, and labor groups, and to highlight Catholic social teaching to inspire others to help. Maurin focused on group action, locating houses of hospitality where works of mercy could be performed and farms to provide for the needy.

Figure 2: Dorothy Day in Museum of the Bible’s “Human Rights” exhibit on the Impact of the Bible Floor.

From its base in New York, Catholic workers went to other cities to form their own Catholic Worker houses. Within a few years, 33 Catholic Worker houses and farms dotted the country. Although the newspaper, hospitality houses, and performing the works of mercy were the movement’s top priorities, Catholic Workers also joined protests and labor pickets, helped house and feed strikers, picketed the German consulate in 1935, and called for boycotts of stores where low wages or poor working conditions existed. All of these activities stemmed from their reliance on biblical teachings, from the outcry of the Old Testament prophets over social injustices to the vision of a new society espoused by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount, to the teachings of the early church about how to treat one another regardless of social distinctions.

Day once wrote “What we do is very little, but it’s like the little boy with a few loaves and fishes. Christ took that little and increased it. He will do the rest.” The mission of the Catholic Worker Movement is still alive. Today there are 180 Catholic Worker houses in the US and around the world. To learn more about Dorothy Day and the Bible’s influence on the labor movement, listen to this short book minute and visit our “Human Rights” exhibit on the Impact of the Bible Floor at the museum.

Figure 3: In our “Human Rights” exhibit, there are other stories of individuals who changed the world through their desire to live out the teachings found in the Bible.

By Judy Hilovsky, Copywriter and Copyeditor