No Longer Hidden: The Legacy of Dorothy Vaughan

It’s the 1940s in Hampton, Virginia. Jim Crow laws keep facilities, like bathrooms and lunchrooms, separated between races. Women, only about 34% of the workforce, hold low-paying jobs as secretaries or factory workers. The Civil Rights Act protecting against workplace discrimination wouldn’t be enacted for another fifteen years. Even though Executive Orders 8802 and 9346 offered some protection at a federal institution like the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), women of color still faced nearly insuperable obstacles. And yet, facing these barriers, Dorothy Vaughan, a 39-year-old Black woman working as a “computer,” would become manager of the computing program at NACA and play a critical role in putting man on the moon.

Figure 1: In 1943, Dorothy Vaughan was hired by NACA as a mathematician working in the computing pool, one of “the girls,” as female employees were called then. Courtesy of Ann Vaughan Hammond, Daughter of Dorothy J. Vaughan.

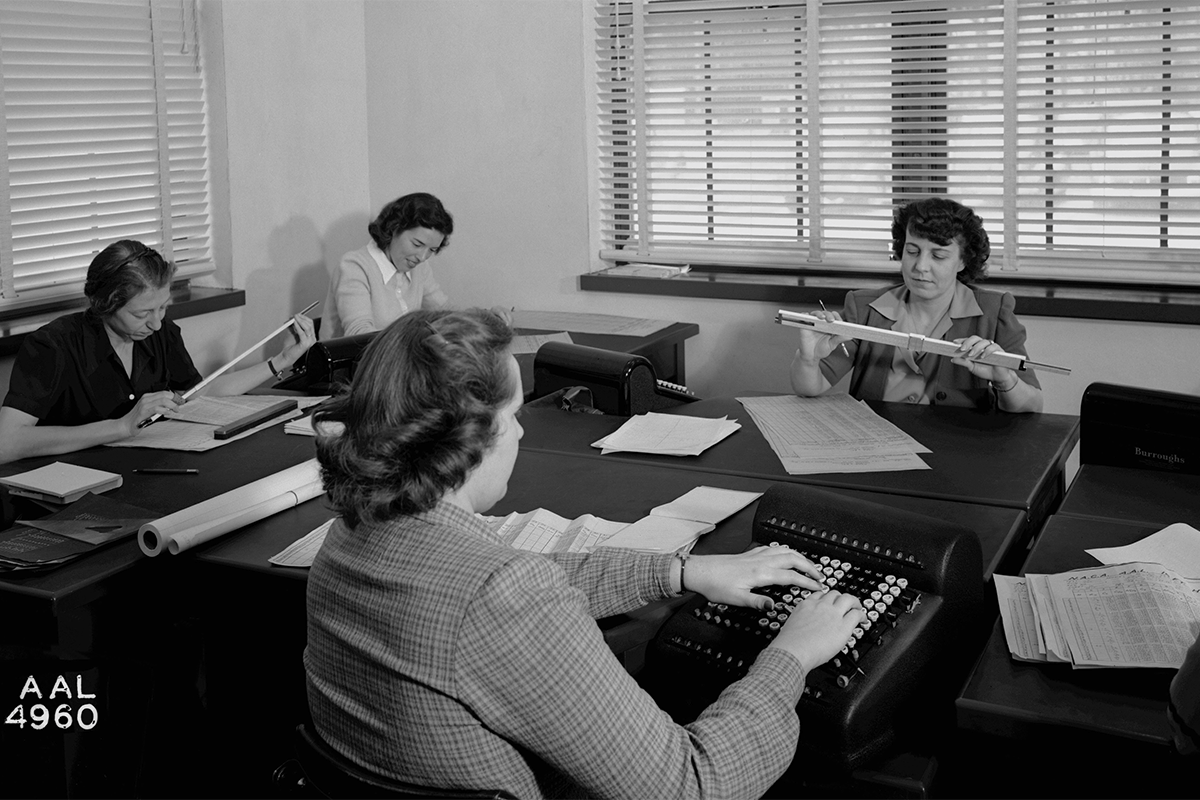

Back then, being a “computer” was an occupation. Far from the tool we use today to scroll through social media, human “computers” at NACA produced mathematical calculations that figured into nearly every operation the agency was planning. Originally a white man’s job, the field became quietly dominated by women—who worked at a cheaper pay rate—during World War II. With pencil and paper, they worked marathon hours on mathematical computations, figuring out the problems that meant success or failure, life or death for the men piloting missions. Internally lauded for their precision and sought out for their work by male engineers, NACA women were largely barred from supervisory positions and job title promotions, confined to computing, which was mostly viewed as lesser work despite the specialization needed for the job. For “colored computers,” as African American women were called then, the obstacles were steeper. Black women were navigating these new opportunities, facing pressures of both gender and race. Their challenges were simultaneously personal and societal. To be taken seriously in a heavily male workplace and prove their abilities to justify their community’s place in a world in which they routinely faced cruel prejudice was a daily trial—one in which they were determined to succeed.

Figure 2: Human “computers” working on wind tunnel test data in 1943.

The majority of human “computers” were white women, who joined the computing pool in 1935. It wasn’t until 1943, two years after Executive Orders 8802 and 9346 established desegregation in the defense industry and the Fair Employment Practices Committee, when Black women joined the ranks of human “computers.” Credit: NASA.

In 1949, six years after starting at NACA, Dorothy Vaughan crashed through the glass ceiling by becoming the first Black woman manager of West Computing, a division of Black women workers at NACA previously managed by white women. During her tenure, Vaughan took radical initiative to build bridges across the color and gender divide, collaborating with white “computers” while planning and strategizing project teams with male colleagues. She advocated for all women regardless of their race, pushing for pay raises and promotions. Vaughan created and fostered a chain of support among her Black colleagues. The women who came into her managerial pool were propelled forward onto new paths in their careers and played critical parts in the development of air technology. These were opportunities young Black women in other parts of the country hardly got, and the achievements of these young women were overshadowed for decades.

Figure 3: Dorothy Vaughan was portrayed by Octavia Spencer, right, in the 2016 hit movie Hidden Figures, based on the nonfiction book by Margot Lee Shetterly.

In 1958, nearly 10 years after her promotion, NACA merged with similar agencies to become NASA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, pivoting its mission from advancing airplane technology to including outer space discovery. The agency also integrated the workplace. The Space Race, like World War II, created a need for mathematicians and engineers working around the clock. Many in West Computing moved to the new Analysis and Computation Division. Foreseeing the rise and staying power of electronic computers, Vaughn taught herself to code in FORTRAN—she is among the first female coders—and instructed other Black women in the computer language, leaving the door open for future generations of women programmers at NASA. Her work earned her a spot on the Scout Launch Vehicle Program, which sent more than a hundred satellites into space and had an overall 96% success rate. With the ongoing downsizing of NASA after having put man on the moon, Vaughan retired in 1971. In a 1992 interview, Vaughan reflected on her time in the agency and recalled, “What I changed, I could; what I couldn’t, I endured.”

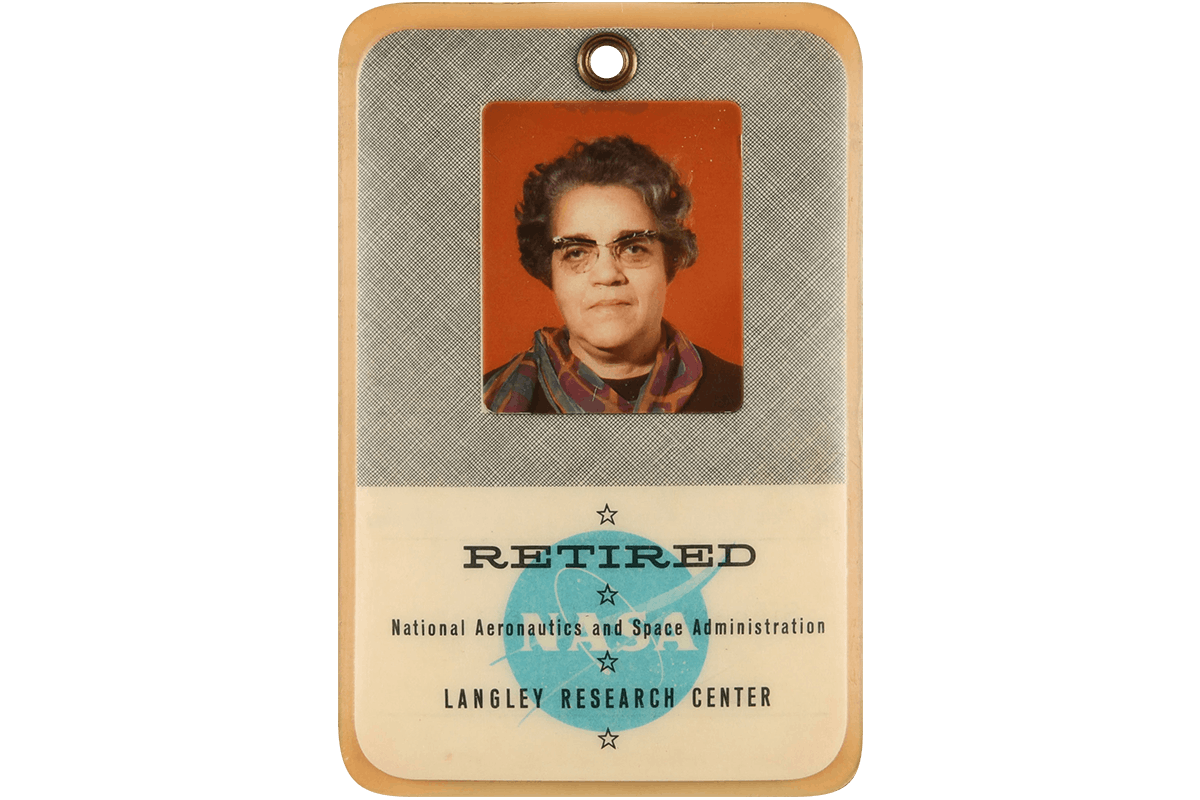

Figure 4: Dorothy Vaughan’s NASA Retirement ID card. Displayed in Scripture and Science: Our Universe, Ourselves, Our Place, through January 15, 2024. Courtesy of Ann Vaughan Hammond, Daughter of Dorothy J. Vaughan.

While crunching numbers and then programming code to break scientific boundaries, Vaughan was a steadfast Christian and a member of St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal Church in Newport News, Virginia, for more than half a century. There, she participated in the music department, often playing the piano, and the Dora Brown Missionary Society. She also served in the Women’s Missionary Society of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Museum of the Bible’s newest exhibition, Scripture and Science: Our Universe, Ourselves, Our Place, highlights Dorothy Vaughan’s story and showcases her personal Bible from 1979, her NASA retirement ID card, and an African Methodist Episcopal Church award honoring her service in the STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) fields.

We invite you to come learn more about Dorothy Vaughan and the interaction of scripture and science in her life and the lives of many more scientists throughout history in Scripture and Science: Our Universe, Ourselves, Our Place. The exhibit runs through January 15, 2024. You can learn more about it on our website.

By Christy Wallover, Exhibit Developer

Sources:

Shetterly, Margot Lee. Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2016.

https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/hidden-figures-and-human-computers

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/vaughan-dorothy-johnson-1910-2008/

https://blog.girlscouts.org/2017/01/dorothy-vaughan-meet-girls-behind.html

https://blog.sciencemuseum.org.uk/nasas-overlooked-star/

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/nasas-west-area-computers

https://www.farmvilleherald.com/2017/01/from-moton-to-nasa/

https://galsguide.org/2018/02/09/dorothy-vaughan-your-gal-friday/

https://www.history.com/news/human-computers-women-at-nasa

https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/civil-rights-act

https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/dailypress/name/dorothy-vaughan-obituary?id=15017192

https://www.nasa.gov/content/dorothy-vaughan-biography

https://scientificwomen.net/women/vaughan-dorothy-103

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/history-human-computers-180972202/