Uniting Souls: DC Emancipation Day and All Souls Church Unitarian

DC Emancipation Day is a widely celebrated event in the nation’s capital with a long and complex history, but what connections does it have with the Bible?

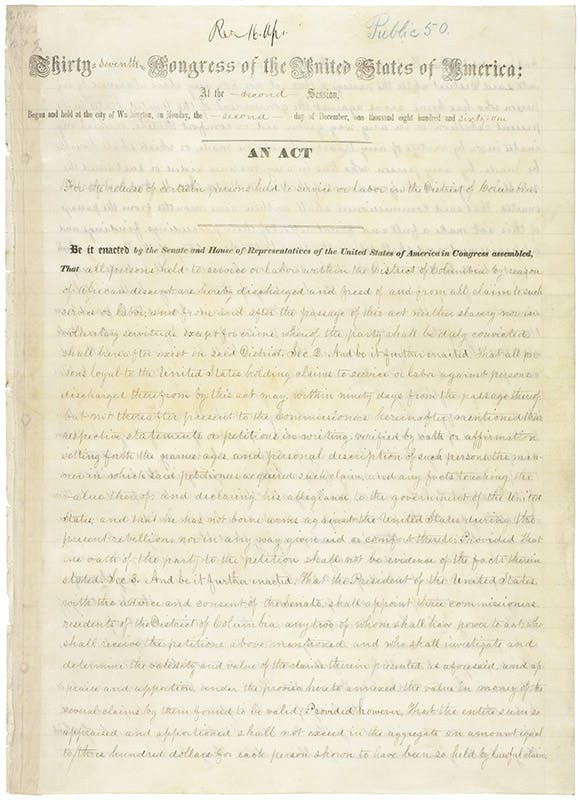

The District celebrates DC Emancipation Day annually on April 16, the date Abraham Lincoln signed the DC Compensated Emancipation Act in 1862. It outlawed slavery in Washington, DC, offering compensation to slave owners for their loss of “property.”

Figure 1: "An Act of April 16, 1862 [For the Release of Certain Persons Held to Service or Labor in the District of Columbia]." National Archives and Records Administration, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Along with the immediate emancipation of enslaved Africans was the award to the “owners” of up to $300 for each enslaved person released if they continued their loyalty to the Union. Each former enslaved person received up to $100 if they migrated to the United States, although few took this offer. Overall, the act resulted in roughly 3,100 enslaved people becoming free and is the only instance in American history where people gained compensation for the emancipation of enslaved persons. The DC Emancipation Act is further important, however, because it laid the groundwork for the Emancipation Proclamation that would be ordered a year later.

The Bible played a part in the reasoning behind emancipation as some passages rebuked slavery. One example is Galatians 3:28, which states, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Another example comes from Angelina Grimke, who wrote “Appeal to the Christian Women of the South.” In her letter, aimed at her sisters in faith who were also part of wealthy, slaveholding families, Grimke refers to several biblical verses, such as Deuteronomy 23:15–16 and Leviticus 25:10. Although her pamphlets ended up being burned for her actions of promoting abolition, her efforts show the Bible’s use in the fight against slavery.

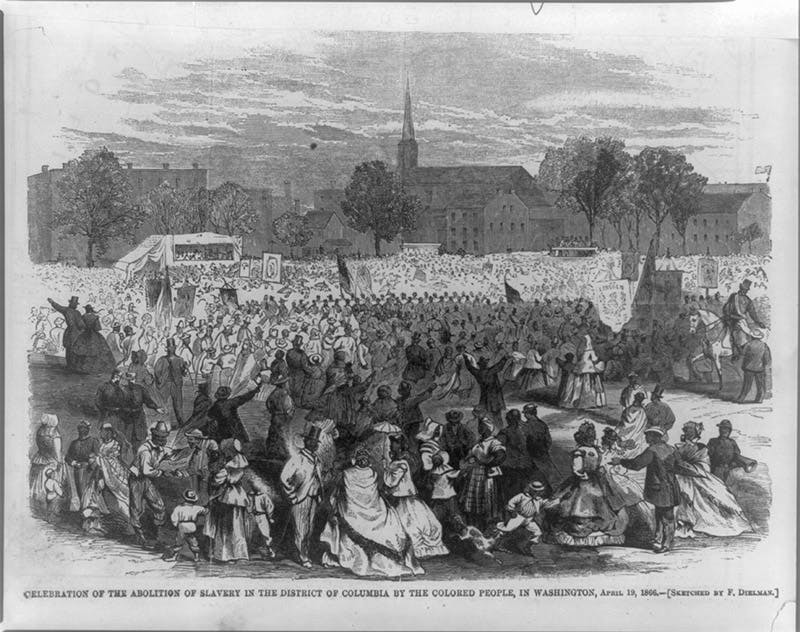

In the wake of emancipation, enthusiasm and celebration sprouted all over the city. In his book The Negro’s Civil War, James M. McPherson reprinted a letter by a free Black man who told two women about the signed act. One woman reacted by saying, “Let me go and tell my husband that Jesus ‘has done all things well,’” quoting the crowd’s sentiment about Jesus’s miraculous act of healing in Mark 7:31–37. The author of the letter wrote, “As a Christian I can but kneel in prayer and bless God for the privilege I’ve enjoyed this day.” The biblical idiom in both statements shows the Bible’s influence in everyday life, among the formerly enslaved as well. Parades began in 1866, showcasing African American pride and joy over their freedom. Presidents Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant even attended the parades, which helped to acknowledge the new freedoms of African American people.

Figure 2: "Celebration of the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia by the colored people, in Washington, April 19, 1866," Harper's Weekly, vol. 10, no. 489 (May 12, 1866): 300. Library of Congress.

Since 1862, celebrations, including parades and speeches, had been held annually. Famous abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, would make appearances and voice their arguments for more change and equality. Douglass would often make distinctions between “the Christianity of this land,” which was used to justify slavery, and “the Christianity of Christ” in order to reject biblical justifications of slavery. In Douglass’s memoir, he made this comparison clear when he stated, “They strain at a gnat, and swallow a camel,” referring to Matthew 23:24 when Jesus scolds the Pharisees for their hypocrisy. Although these celebrations were successful for some time, conflict among planning committees, money problems, and crime halted them in 1901; they would not resume until 2002.

Fast forward to the second half of the twentieth century, to All Souls Church Unitarian on Harvard Street in northwest DC, where two people’s efforts, separated in time, would propel integration, lead the fight for equality, and one day see the celebration of DC’s emancipation renewed. Through their combined efforts, celebrations began again in 2002, and DC commemorated the implementation of the DC Emancipation Act now as DC Emancipation Day, which became an official holiday for the area in 2005.

Figure 3: All Souls Church Unitarian. Library of Congress.

Reverend A. Powell Davies was a minister at All Souls who did much in the fight for equality and integration. From 1944 to 1957, he advocated against racial inequalities in DC, organized fundraisers for those struggling in foreign countries, and created the first integrated youth group in the city, named the Columbia Heights Boys Club. In this club, boys would learn activities such as billiards, games, and carpentry from volunteers. As a strong fighter for racial equality, Powell said, “The American commitment is to universal justice, the rights of all people, not the special interests of some,” and his constant efforts toward racial integration helped to make a more equal Washington, DC.

Loretta Carter Hanes was an All Souls member whose fight for equality included the renewal of DC Emancipation Day celebrations. Although Hanes’s and Davies’s time did not overlap, their work finds a connection through All Souls’ tradition of fighting racial injustice. Hanes’s fights would include Black education and cultural initiatives, voting rights, and DC Emancipation Day celebrations.

Hanes’s revival of DC Emancipation Day started small, with a celebration at All Souls Church in April 1991. She was not content with this level, however, believing the celebration needed to be citywide in order to make its residents more aware of racial inequalities. Hanes then took it upon herself to educate and lobby DC officials, and to lay a wreath every year at the Freedman’s Memorial statue in Lincoln Park on April 16 in commemoration of the DC Emancipation Act, beginning that same year. Soon enough, parades started again, in April 2002, just over a century since they had been canceled. For her relentless efforts, Hanes today receives credit for making DC Emancipation Day an official public holiday, which it became in the District in 2005.

The next time you’re in DC, visit the museum’s Bible in America exhibit to see artifacts related to abolition, the Civil War, the civil rights movement, and other prominent people and events associated with the African American church. And take time to see the Bible in DC at some of the historical places associated with DC Emancipation Day, such as All Souls Church Unitarian and Lincoln Park.

By Sarah Kim, Editorial Research Intern