A Firm Foundation: The Story of the Vernon A.M.E. Church

In anticipation of Black History Month, I wanted to write about an object that was recently donated to Museum of the Bible, and is now on display in the museum's “Bible in America” exhibit. Compared to other objects in the museum, this new addition might not seem impressive. It does not glisten like an illuminated manuscript. It was not owned by an influential minister, popular celebrity, or prominent politician. In fact, the object is a small, unassuming fragment of stone. Sometimes, however, the most unassuming objects bear witness to some of the most powerful stories. This stone fragment was once part of the foundation of Vernon A.M.E. Church of Tulsa, Oklahoma, the only black-owned structure to survive the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Here is a glimpse of the stories it can tell.

Figure 1: STN.000119, the unassuming stone from the Vernon A.M.E. Church foundation. It can be seen on our Collections page here.

Vernon A.M.E. Church was founded in 1905, two years before Oklahoma reached statehood. Tulsa was a small town on the cusp of big change at this time. The discovery of oil would soon remake the city's fortune. Between 1910 and 1920, Tulsa’s population grew from around 10,000 to 100,000. Seemingly overnight it became home to modern office buildings, dozens of new housing developments, schools, and parks, an electric trolly system, and even a commercial airport. Some residents began referring to Tulsa as the “Magic City.” Some suggested the nickname, “City of Churches,” due to the number that had been newly constructed or expanded. Tulsa was a city on the move, inventing itself along the way.

Vernon A.M.E. was in Tulsa’s Greenwood District, a predominantly black neighborhood that flourished in these years. By 1920, around 11,000 African Americans called Greenwood home. While some had lived in the area for generations, most had recently arrived from places like Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas in search of a better life. Segregation severely restricted the rights of black Tulsans. Greenwood became a city within a city, boasting a library and two schools, a hospital, movie theaters, grocery stores, restaurants, clubs, jewelers, tailors, and hotels. Because of this economic prowess, the district came to be referred to as “Black Wall Street.” Its success, and the sense of independence it fostered, was a source of pride for residents.

Faith was part of daily life in Greenwood, as it was for most Tulsans. Vernon A.M.E. was one of 13 churches in this area. Within a few years of its founding, its membership grew from 8 to 71. In 1908, it purchased the land that would become its present site and, in 1914, it began construction on the basement—the only part of the original building that survives today. While its membership included doctors, lawyers, realtors, and entrepreneurs, most worked as janitors, maids, porters, or day laborers. As Vernon A.M.E. nurtured people spiritually, it also served the community. At a time when African Americans faced persistent racism and anti-black violence, it was also a source of security, stability, and empowerment.

Tulsa’s rapid transformation, along with Greenwood’s remarkable success, made it unique in some ways. However, like other cities across the nation, it was deeply divided along racial lines. Such divisions could erupt into violence. In 1919, over two dozen race riots broke out in cities ranging from Washington, DC, to Knoxville, with white mobs invading black neighborhoods, attacking men and women, and destroying property. In 1921, one of the worst cases of racial violence in American history took place in Tulsa.

On the night of May 31, a white mob attacked the Greenwood District. The violence was sparked by accusations that an African American teen had assaulted a young white woman, and was fueled by white supremacist fear and resentment of Greenwood’s success. Throughout the night and the following day, the mob assaulted residents, looted homes, and set fire to businesses. At some point, several people fled to Vernon A.M.E., huddling together in a basement closet as flames consumed buildings nearby. When it was over, nearly 35 city blocks were destroyed. Hundreds of men, women, and children were killed or injured. An estimated 9,000 residents were left homeless.

Figure 2: Image of Vernon A.M.E. Church taken 60 days after the Tulsa Race Massacre. Photo courtesy of the Tulsa Historical Society.

Vernon A.M.E. was almost destroyed. Only the basement and parts of the lower level survived. In the weeks and months that followed, the church helped the community begin to recover. The Sunday after the massacre, members gathered in the damaged building to celebrate communion. It hosted a high school graduation ceremony and other community events. It helped distribute food and aid to those who had lost their homes and businesses.

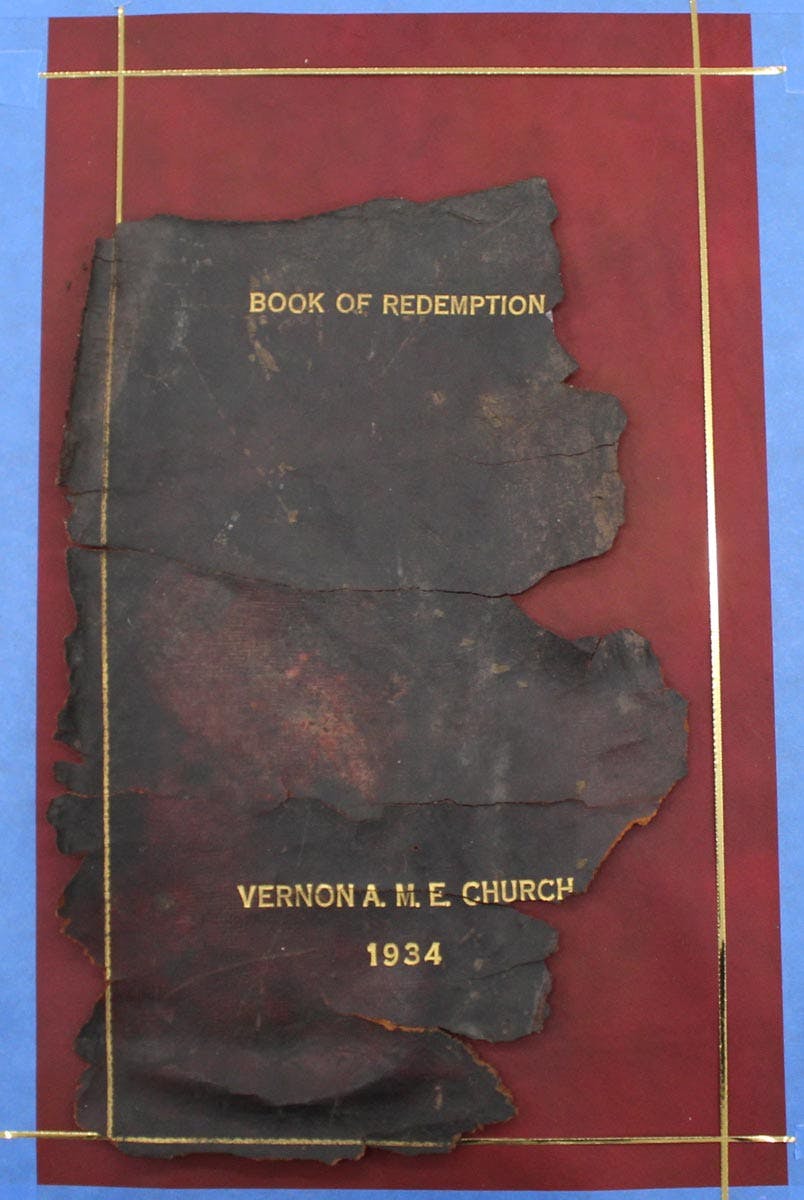

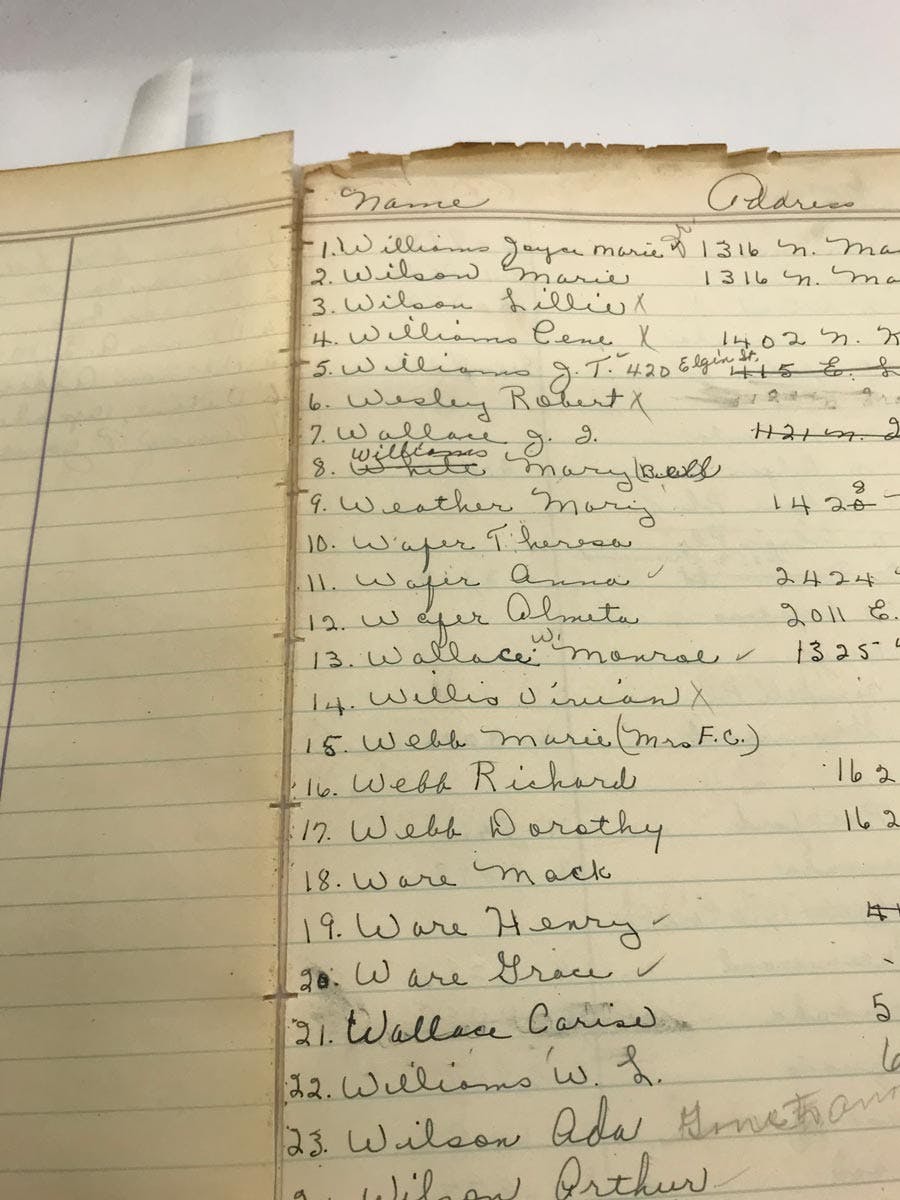

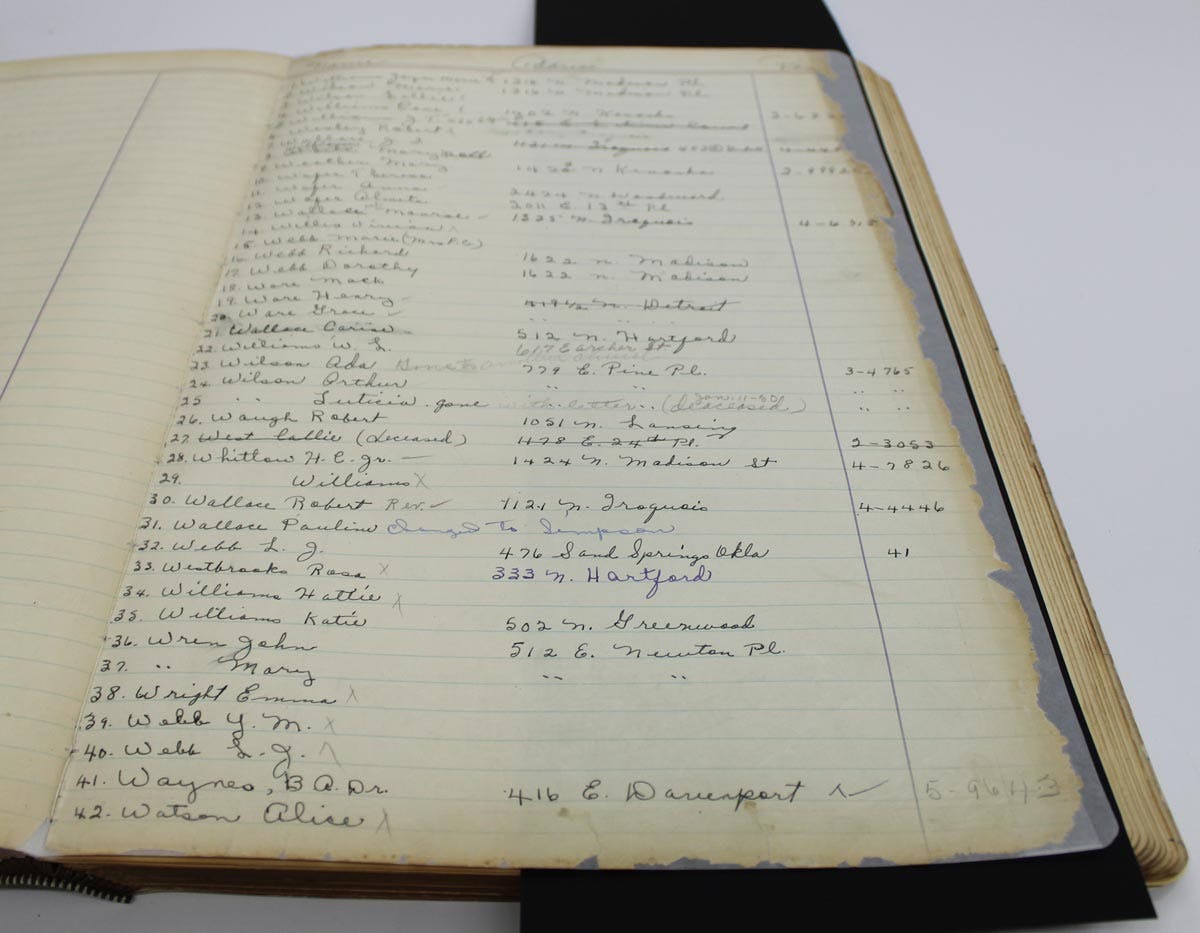

Plans were almost immediately put in place to rebuild the church on the surviving foundation, despite receiving no insurance payments or government assistance. Members raised a building fund of around $1,100. The main church building was completed in 1928. By this time, membership had doubled to approximately 400. By 1940, membership rose to 800 and all debts had been paid. The names of donors who helped fund the new building were recorded in a ledger that members called the “Book of Redemption.” The resilience and tenacity of Vernon A.M.E.’s members were indicative of the broader Greenwood community. People returned. Homes were rebuilt. Businesses opened their doors. Greenwood thrived once more.

Today, Vernon A.M.E. is the only remaining black-owned structure from the Black Wall Street era. It remains a vital part of the Greenwood District, most recently distributing hundreds of thousands of meals in the community during the COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns. It has embraced its past as a way to teach people about the Tulsa Race Massacre and America’s sad history of racism. Recent renovations of the church included a prayer wall for racial reconciliation.

In June 2020, a year before the massacre’s centennial, Vernon A.M.E.’s then-pastor, Rev. Dr. Robert Turner, gave a tour of the church to Sarah Stitt, First Lady of Oklahoma. He showed her the “Book of Redemption,” which had been recently rediscovered in the church’s basement. The ledger was in fragile condition. Its cover was warped, its pages loose and water damaged. Hoping to save this piece of history, Rev. Turner and First Lady Stitt contacted Museum of the Bible.

Figure 3: This is all that's left of the original front cover of the "Book of Redemption."

Figure 4: The condition of the spine of the original "Book of Redemption."

Over a period of several months, the museum’s conservators worked to restore the ledger and return it to the church in time for their centennial commemoration.

Figure 5: Detail of a page recording surnames beginning with W in the original "Book of Redemption."

Figure 6: Image of the same page as above, of surnames beginning with W, in the facsimile edition of the "Book of Redemption" made by Museum of the Bible.

As a token of appreciation, Rev. Turner donated to the museum a fragment of the church’s original foundation, which construction crews had unearthed during renovations, the foundation that had been laid in 1914 and on which members who survived the Tulsa Race Massacre rebuilt their church.

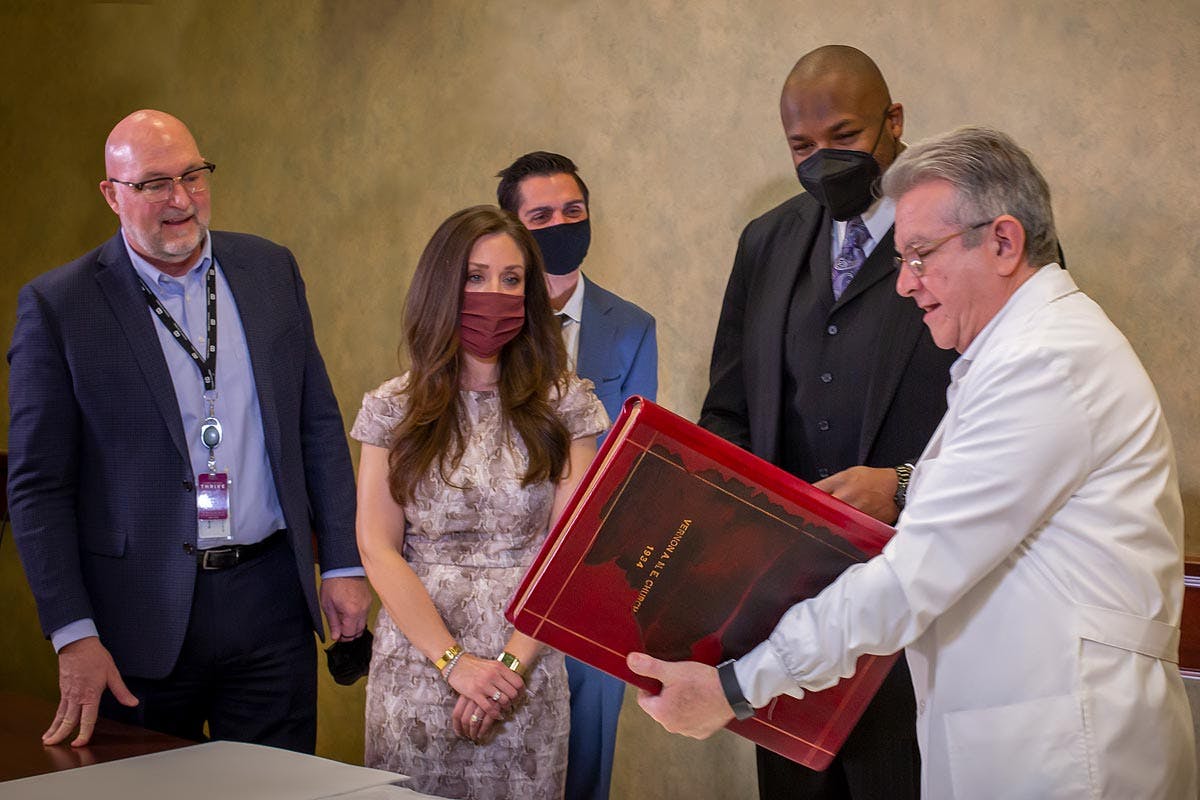

Figure 7: Museum of the Bible Conservator Francisco Rodriguez presents the restored "Book of Redemption" made by the museum. From left: Chief Administrative Officer Dave Suey, First Lady Sarah Stitt, Director of Collections & Curatorial Anthony Schmidt, Rev. Dr. Robert Turner, Conservator Francisco Rodriguez, March 2021.

This unassuming stone fragment is now on display in Museum of the Bible’s “Bible in America” exhibit.

Figure 8: The Vernon A.M.E. Church foundation stone fragment on display in the Bible in America exhibit at Museum of the Bible.

As guests move through the gallery, we hope it will convey some of the ways the Bible has inspired African American communities and the important, but sometimes complicated, role it has played in African American history. Biblical faith helped motivate people to build Vernon A.M.E., and then rebuild after a senseless tragedy. Perhaps most importantly, it helped embolden them to resist white supremacism and racial injustice, just as it has with other figures before and after the Tulsa Race Massacre. That work continues today.

By Dr. Anthony Schmidt, Director of Collections & Curatorial

*Header photograph of Vernon A.M.E. Church today. Photo courtesy of Sloan Hepler Photography.