From the Podcast: The Syriac Bible

Recently on our podcast, Dr. Jeff Kloha, our chief curatorial officer, interviewed three special guests, Sister Jincy, with the Assyrian Church of the East, Fr. Jacob Thekkeparambil, with the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, and Dr. Daniel McConaughy, Professor Emeritus at California State University, Northridge.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and space. To hear the whole interview, listen to it on our podcast or watch the episode on our YouTube channel.

Jeff Kloha: The theme today is the Syriac Bible and the history of the Syriac Church. We have with us Sister Jincy, who came to examine some Syriac manuscripts here at Museum of the Bible. We also have with us Father Jacob Thekkeparambil, who's with the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church based in southwestern India, which has a long history of Christianity. And Daniel McConaughey, who's working on a project on the Syriac text of the book of Acts.

Daniel McConaughy: I work in the field of textual criticism, so Museum of the Bible is very important for that because it possesses Syriac manuscripts.

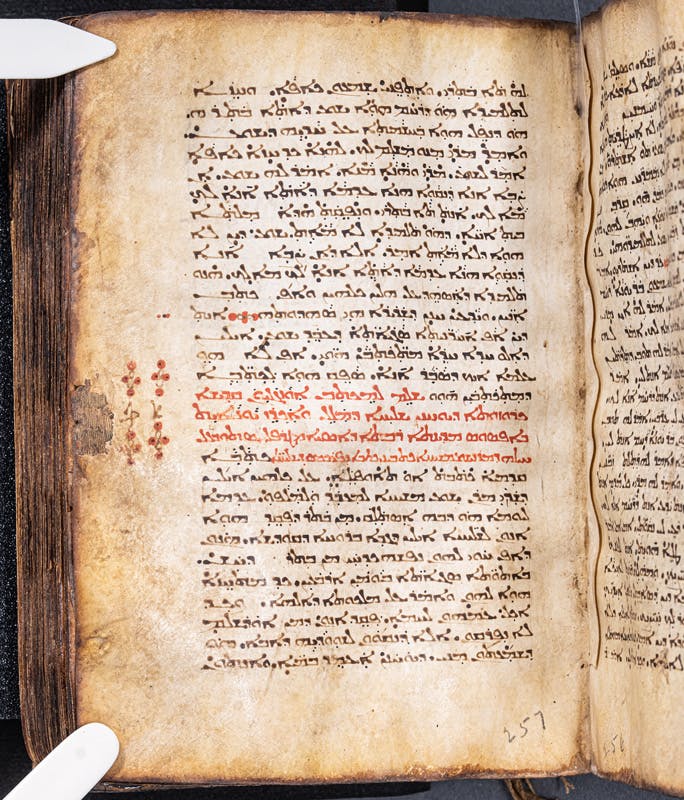

Jeff: That's what you were doing yesterday, [you] spent the afternoon looking at one of our Syriac manuscripts. Would someone like to describe that manuscript and what you came to look for?

Sister Jincy: That manuscript is based on the New Testament Peshitta [=Syriac] Bible, and it's very interesting to know that they’re writing, from Saint Paul, all these epistles. But in these manuscripts after the Gospels, we can see the Acts of [the] Apostles, then [the epistles of] James or Peter, like that. Then last we go to the Saint Paul epistles.

Jeff: So, it has the Catholic Epistles after Acts and then to the Pauline Epistles. So, a little different order.

Sister Jincy: At the end, we can see Hebrews there.

Jeff: And how old is this manuscript you're looking at?

Sister Jincy: I don't know exactly, maybe it's fifteenth century. We don't know exactly but with the carbonic [14C testing], maybe we'll find out later.

Daniel: Yes, that text is the Khabouris manuscript that we could read the best, and it has some archaic West Syrian readings. I'm working with a scholar in Germany and we had certain test verses. I was able to look at 52 verses from certain images, and it shows a number of archaic forms of Syriac words in Acts, so he thinks we should collate it.

Figure 1: The Khabouris Codex, open to the beginning of the book of Acts. Image © Museum of the Bible, 2023.

Jeff: The Syriac Bible is a very early translation. But before we get to the Bible itself, could you describe the history of eastern Christianity, the Church of the East, which is a very large and ancient church. Could you tell us just a little of the history of that church, its connection to the apostles, some of that early history down to the present day?

Sister Jincy: It's a long history. We can start from the Saints Addai and Mari. Sometimes people say Addai is Saint Thaddeus, you know, the one Abgar legend. In that legend, they're saying that King Abgar, the Ukkāmā, wrote a letter to Jesus and he wanted to get healed. But at that time, Jesus did not go there. At the end, Saint Thomas sent Thaddeus there and healed him. And some traditions say that Saint Thomas went there, too, and after that he came all the way to India, Central Asia.

Jeff: So, Saint Thomas travelled to India, which is a very old and seemingly reliable tradition.

Sister Jincy: They mentioned Mylapore, in the state of Tamil Nadu, there's a tomb of Saint Thomas there.

Jeff: Not out of the question that the church goes back to the first century in India.

Fr. Jacob Thekkeparambil: Before Thomas went to India, he passed through Mosul, in modern day Iraq, so there is a famous Saint Thomas church. And in fact, the relics, which our West Syrian Orthodox Church has of Saint Thomas, were brought from Mosul.

Sister Jincy: There's a lot of connection between the Middle East and India. Even the Silk roads, I think most people know.

Jeff: About the Silk roads, there’s massive travel back and forth, and Christians travel on these roads; all kinds of exchange of ideas and back and forth for centuries and centuries.

Fr. Jacob: For early Christianity, Iraq was almost like our mother country from the point of view of liturgical tradition. And the influence of the easterly pronunciation is still understandable and is still heard.

Jeff: So the very ancient languages reflect this history.

Sister Jincy: Even the liturgy itself, we are using the same liturgy. The Church of the East use the Addai and Mari liturgy, the oldest one, and we have the tenth-century manuscript. Still, we are using the Syriac as liturgical language in our churches. All the priests can sing and recite the Syriac.

Jeff: Is Syriac still spoken every day, or is it kind of limited?

Sister Jincy: No. Liturgical purposes, Classical Syriac. But the Assyrian people, they are speaking Suret. But the Assyrian people also use, for the liturgical purpose, the Classical Syriac. But we have the West Syriac tradition in India, from the sixteenth century onwards, we are using the West Syriac tradition.

Jeff: How many Christians are in India today in the church?

Fr. Jacob: Probably about 9,000,000 altogether, so distributed in seven churches of Syriac tradition.

Jeff: It's still a large church.

So, the Syriac Bible, very early translation and very important for understanding the history of the text of the Bible, both its wording and the canonical questions—which books are in the New Testament. When was the Syriac translation produced?

Daniel: Probably the fourth century, and by the seventh century was very standardized. So, one reason we're interested in the Khabouris manuscript is it has some readings from the early period before it was completely standardized. There was another version before that, but it only exists in two manuscripts, that's the Old Syriac Gospels. So, it's very old, and it has a shorter canon than the Greek.

Jeff: So, they have a few books less in their New Testament. The translation itself you think is probably fourth century, the Peshitta translation?

Daniel: Yeah, it’s began to evolve, but certainly fifth century, no one knows really. It’s just always been there.

Fr. Jacob: At first there were translations of liturgical passages. Not the whole Bible, as such. But whatever is needed for the liturgy, for example, the Epistles or the Gospels. These were circulated among the clergy and also among the deacons, who were actually doing the reading. However, one should note that there is no reading from the book of Revelation.

Jeff: Right, that's also in the Greek Orthodox Church. They don't read the liturgically from Revelation. So, it's not rejected, but it's not a liturgical book, right? But it's not in this Khabouris manuscript, correct?

Daniel: It's not. Revelation is not in the Peshitta [= Syriac] version of the New Testament. Peshitta lacks 2 Peter, 2 [and] 3 John, Jude, and Revelation.

Jeff: Yes, which lines up with what some early church fathers also said about which books are most important in the east, so it all fits together, right?

Dan, you’re working on producing a new edition of the book of Acts. What's your work, and what are you hoping to find?

Daniel: So I'm working on the book of Acts, a critical edition. I began work on this a long time ago and now I'm collaborating with a scholar in Germany, and we've collated about 55 Peshitta manuscripts (we'd like to include Khabouris). We have also collated lectionary manuscripts, just taking the readings of Acts out, and we'll prepare an edition that will reflect the most archaic form of the Peshitta. We were interested in those western versions. The eastern version dominated over time and it became standard, but this western is older. But just here and there, it says usually the same thing. So, we'll have the critical apparatus, which will include the readings from all the manuscripts that wouldn't be reflected in the text itself—we have the text up here in Syriac and then all these notes.

Jeff: Syriac is very similar to Aramaic, which is one of the languages Jesus and the disciples spoke on a daily basis, so it preserves some pretty early traditions, right?

Daniel: Oh yes. There are certain terms in the Peshitta that they just brought over from the original, why not? You know, because the people that spoke Syriac knew the Aramaic.

Jeff: Yeah, right. It's sort of like how we still use the word “amen.”

Daniel: And the funny thing is that Peshitta will, where the Greek has some Aramaic, it says “which means . . .” Well, the Syriac will reproduce the Aramaic like the Greek and then it just repeats the same thing in Syriac.

Jeff: It just repeats it. You don't need to translate it because it's the same language.

Daniel: But they wanted to preserve that Greek.

Jeff: Interesting translation approach. Very literal to the text, or at least preserving the wording of the text. Fascinating.

Fr. Jacob: And the churches prefer to use translations from Syriac texts rather than even our local language, Malayalam, or English. They prefer to use the direct translations from Syriac Bibles. Although the King James version is there—there is a Malayalam translation of that—and in the beginning, people were reading that, and later on the Syriac churches insisted that the translation should be based on the Syriac version of the Bible.

Jeff: Not based on an English version. Yes, that makes sense. So, it's a very, very ancient church. Long, amazing history. Sister, Father, what's a little of the work you're involved in today there in India with the churches?

Fr. Jacob: Well, it was the dream of all the seven churches of Syriac tradition to have a center of research on the early documents, manuscripts of the Syriac tradition. In 1985, we inaugurated this center, which is called St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute (SEERI). And it was the only center where we could have also some editions of the manuscripts, publications, and all the dictionaries. Syriac dictionaries were not available in India before that. Not only that, after 10 years of our own research, Mahatma Gandhi University adopted us as their research center for Syriac studies, offering us the possibility of teaching a master’s degree program and a PhD program.

Jeff: Fantastic. Focused on studying Syriac texts.

Fr. Jacob: Our government and also the university were very generous to include Syriac because, on the one hand, there are lot of Malayalam words of Syriac origin. So, it was not only a liturgical language, it had already influenced the culture and the local language of south India. So that's why people were interested to have a research center for Syriac.

Jeff: Well, congratulations, that's great. And sister, what's some of the work you're involved in?

Sister Jincy: Now I am the research guide of his institute and the Mahatma Gandhi University. Then, teaching in Syriac and other places like the Catholic seminary. The Church of the East has one theological institute in Sydney, Nisibis Theological Institute, via online, I’m teaching there too. The last three years, the bishops appointed me as a manager of the schools over there in our town, Thrissur. So I am working there too.

Jeff: Administrator, scholar, all kinds of things. Fantastic.

Well it’s been a delight to have you here with us the last couple of days and thank you for sharing about your work and the church in India and the Syriac Bible. We look forward to the publications on this manuscript and learning more about it.

Fr. Jacob: Thank you very much for honoring us with your invitation [to] this prestigious institution. We have had a golden opportunity to be received by you and also to see the museum and all that you do for the Bible.

Jeff: And thank you for your partnership in this work.

Sister Jincy: Thank you very much for your wonderful hospitality, too.

Jeff: You're most welcome and come back again.