Provenance and Book History

If you ask a museum curator about their work, you’ll likely hear the word provenance in their answer. In the world of museums and collecting, provenance refers to the ownership history of an object. Museums and collectors care about provenance for several reasons.

First and foremost, provenance bears upon the legality of an object. Much like a title search on a house, provenance research aims to uncover any legal complications in the ownership history of a book, manuscript, or other antiquity. Unfortunately, it’s often far more difficult to trace the legal history of a book or manuscript than a house. A book moves around quite easily (unlike a home), and there is often limited documentation involved. It might be sold online, passed down within a family, or even change hands in a garage sale. It may have been lost, stolen, or both at various points in its history. In some instances, an object may appear to have a clean history, only for a past legal problem to emerge later, such as Museum of the Bible’s Manuscript 220 or Manuscript 18.

If we look deeper into the past, provenance research can reveal much more than the legal history of an object. A text owned and annotated by a prominent historical figure, for instance, may offer insight into their life and thought. Museum of the Bible’s BIB.003877, a 1542 Vulgate Bible, contains several notes from Martin Luther, including an inscription of Hosea 2:16–17, Luther’s signature, and Luther’s humorous, self-styled sobriquet, “antipapa” (the anti-pope). Another Vulgate Bible in the collection, BIB.003871, was owned by Johannes Bugenhagen, who pastored Luther’s church in Wittenberg and became a prominent Lutheran reformer in Scandinavia. It contains extensive annotations throughout, offering insight into Bugenhagen’s ideas and interpretation of the Bible.

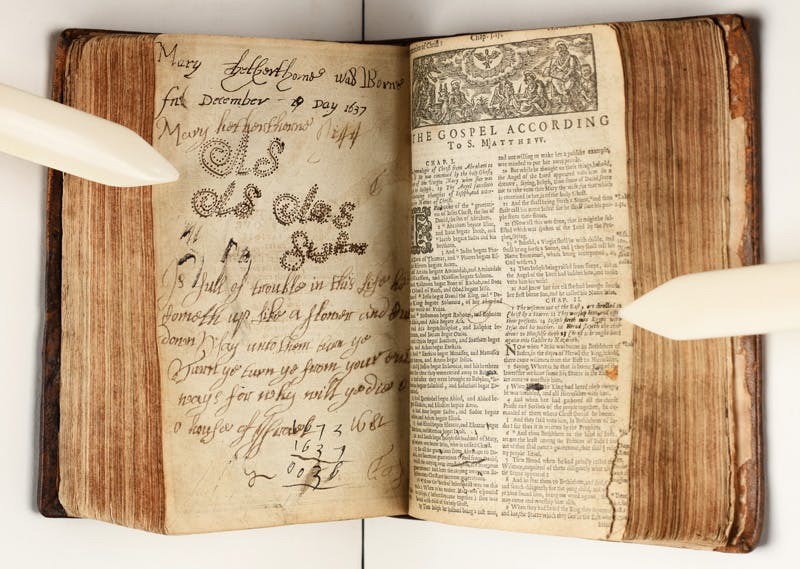

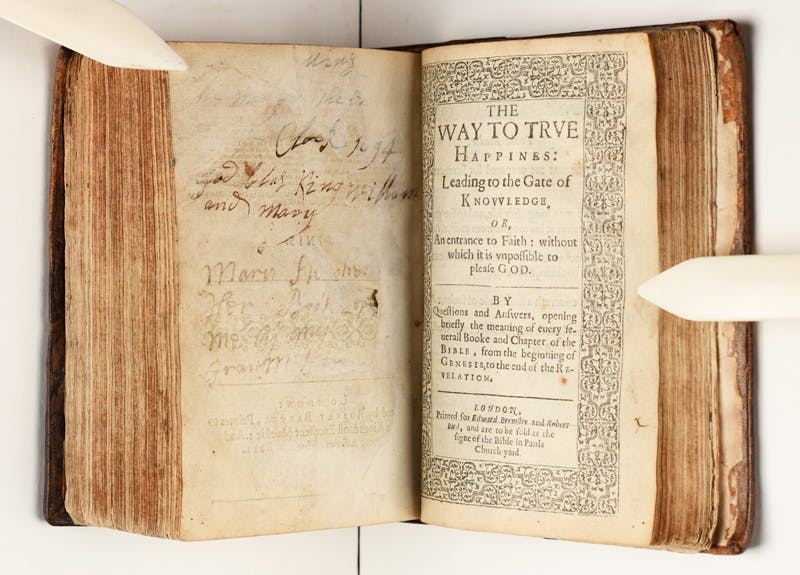

In many cases, the names and annotations in the margins of a book do not belong to famous figures like Luther or Bugenhagen. Nevertheless, they reveal valuable information about the culture and society of the past. A 1631 King James Bible in the Museum Collections, BIB.000197, contains several signatures and notes from a series of women who owned it in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Given that most books in this period were owned and annotated by men, these notes are worthy of attention. They include, among others:

Figure 1: Notes 1, 2, 3.

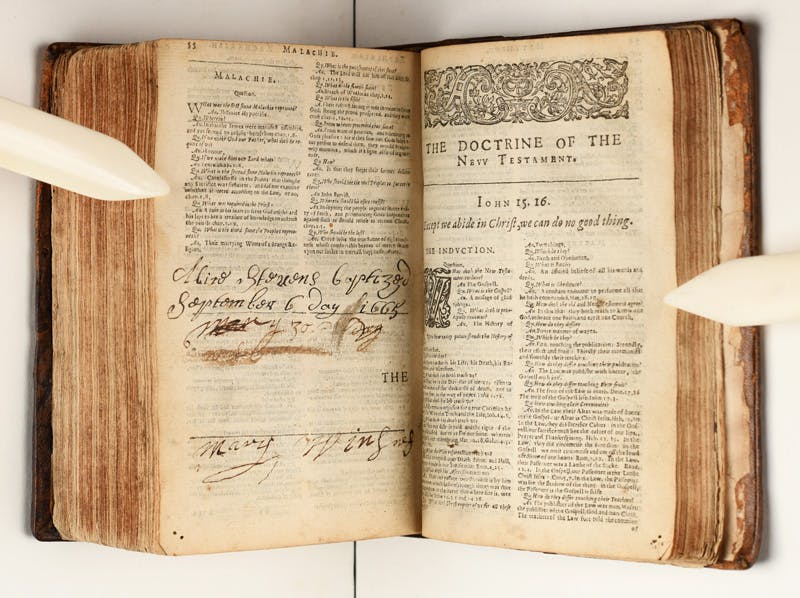

Figure 2: Note 4.

Figure 3: Note 5, 6, 7.

- Note 1: “Mary Hetherthorne was Borne in December - 29 Day 1637.”

- Note 2: “Is full of trouble in this life he cometh up like a flower and cut donn. Say unto them turn ye turn ye turn ye from your evil ways for why will ye die o house of Israel 1682”

- Note 3: “Alles Steyphens”

- Note 4: “Mary Stephens Her Book [left?] me by my grandmother”

- Note 5: “Alice Stevens baptized September 6 day 1665”

- Note 6: “Mary 30 day [illegible]”

- Note 7: “Mary Wins[nef?]”

Who are these women, and what might these limited notes tell us about their lives and their world? The Hetherthorne family lived in and around Wiltshire, England, in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. They were, as English historians would say, the “middling sort”—relatively wealthy and rising through the socio-economic ranks, but far from nobility. They fit the economic profile of a family who might purchase this Bible, which is not quite nice enough for the nobility but far too expensive for the average lower-class family.[1] Stevens, meanwhile, is a far more common name, but parish records from the same area confirm the baptism of Alice Stevens, daughter of John and Mary Stevens, on September 6, 1665, just as Note 5 indicates.[2] Might this Mary Stevens be the former Mary Hetherthorne from Notes 1 and 2, having married and taken a new surname? Only four years later in 1669, the same parish records record the death of a Mary Stevens, the wife of John Stevens.[3] Was this the same Mary Stephens who baptized her daughter Alice four years earlier? Or might it be someone else? Moreover, who is the unidentified Mary in Note 6? A sister of Alice? The future Mary Winsnef in Note 7? The answers to these questions, and many others, require further research, but several immediate observations are possible.

First, regardless of the exact lineage of the individuals mentioned in these notes, this Bible was clearly passed down through several generations of women within a family (or multiple families). In a society where money and assets typically passed from one generation of men to the next, a Bible—and a relatively expensive Bible at that—owned and inherited exclusively by women is interesting. Although one solitary book permits no sweeping conclusions, it might serve as one piece of evidence, alongside many others, in a broader historical investigation. A researcher might ask whether this is a common trend. Do we see many Bibles that were passed down among the women of a family? If we do, does this happen with other books as well? Was the Bible treated differently, or was it owned and inherited like any other possession? Might this tell us anything about the status of the Bible? Or who was meant to have access to its text?

A separate but equally interesting line of inquiry concerns Note 2. Note 2 is a combination of Job 14:1–2 and Ezekiel 33:11. Curiously, though, it does not follow the exact language of the King James Bible, or any other English Bible available at the time. Below is a comparison of the language, with notable differences highlighted for emphasis:

Job 14:1–2

- 1631 King James Bible: “Man that is borne of a woman, is of few dayes and full of trouble. He cometh forth like a flowre, and is cut downe.”

- Handwritten: “Is full of trouble in this life he cometh up like a flower and cut donn.”

Ezekiel 33:11

- 1631 King James Bible: “Say vnto them, As I liue, saith the Lord God, I haue no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but that the wicked turne from his way and liue: turne ye, turne ye from your euill wayes, for why wil ye die, O house of Israel?”

- Handwritten: “Say untothem turn ye turn ye turn ye from your evil ways for why will ye die o house of Israel.”

Again, one book permits no sweeping conclusions, but this might serve as one piece of evidence for a researcher interested in the history of Bible reading, Bible memorization, or other related issues. Why does this text differ from the King James text? Was the author transcribing it from memory? Did she think the differences mattered, or not? How much improvisation was acceptable? What might this tell us about her understanding of the Bible? About her view of Bible translations? About her view of the reliability of those translations? One small clue like this, joined with many other pieces of evidence, might shed light on these questions. In the historical profession, this type of research is known as book history. It considers not only the text of a book, but also its materiality, its publication history, its ownership history, its marginal annotations, and more. It is a laborious endeavor, but the results of book history are continually improving our understanding of the past.

By Wes Viner, Associate Curator of Early Modern Bibles and Religious Culture

[1] Tudor tax rolls indicate that Henry (Henrie) Hetherthorne paid the second highest tax in the village of Great Wishford in 1576, behind only Walter Bonham, the landed gentleman who owned much of the surrounding countryside. See G. D. Ramsay, Two Sixteenth Century Taxation Lists, 1545 and 1576 (Devizes: Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, 1969), 110.

[2] Bishop’s Transcripts, 1605-1679, Overton, Wiltshire, England, 17. Accessed at https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/61187/ on December 13, 2022.

[3] Bishop’s Transcripts, 1605-1679, Overton, Wiltshire, England, 25. Accessed at https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/61187/ on December 13, 2022.