Presti-digitization: Introducing the Digital Imaging Lab at Museum of the Bible

One of the first items I digitized at Museum of the Bible was the Eliot-Indian Bible—the first Bible to be translated into an American Indigenous language (an Algonquian dialect) and the first Bible printed in America. I still chuckle when I remember reading the words “Oi God” throughout the book. This phrase, which honors and praises God’s name, reminded me of the Yiddish “oy.” I began to picture Native communities dabbling in Yiddish. As absurd as the scenario may be, it would not have been possible had that Bible not been preserved for over 350 years. The preservation of artifacts is paramount to museums, and digital preservation is a growing branch within the field of cultural preservation. Museum of the Bible launched its Digitization Department this past September when they hired me, Rebeccah Swerdlow, as their first Digital Imaging Specialist.

What is digitization? In short, it refers to making our Bibles and other texts available in a digital format. For example, at present, I take high-resolution photographs of our Bibles, manuscripts, facsimiles, and (soon) scrolls and make them available to scholars and the public so they can access and enjoy these treasures for their academic and cultural significance. How do I take these high-resolution photographs? With our state-of-the-art digital imaging lab, made possible by a generous grant from the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust. With its specialized equipment, I can photograph different types of artifacts, from books to scrolls to fragments.

As you might imagine, we have a lot of books at Museum of the Bible; one in particular. In digital imaging, we call books “bound material,” and to digitize bound material, the museum uses a device called a BC100, nicknamed “Bessie.” BC stands for “book cradle,” and the “100” refers to the fact that the cradle keeps a book open at exactly 100 degrees for optimal photography without applying any excessive pressure that might damage the book’s spine. The BC100 is an enormous and powerful machine in both the volume of photos it can produce and the power and the amount of digital storage it requires. With it, I have been able to digitize a plethora of fascinating objects, such as a manuscript with rare texts by Galen from the Vlatadon Monastery in Thessaloniki, Billy Sunday’s sermon notebook, and the Eliot-Indian Bibles (It was even more exciting when I got to take a selfie with an expert book conservator from Greece.). With two cameras that capture the left and right pages of a bound object simultaneously, I can digitize hundreds of pages, if not thousands, in just one day. After I carefully review each image in multiple rounds of quality control, the images are made viewable in our online collections database (which you can access here).

What does “quality control” require, you might ask? Just up the road from Museum of the Bible, the National Mall is full of federal agencies like the Library of Congress, the Archives of American Art, the Smithsonian Institution, and the Holocaust Museum, and they, too, are in the process of digitizing their collections. In 2007, 20 federal agencies combined to form the Federal Agencies Digitization Guidelines Initiative (FADGI) “to articulate common sustainable practices and guidelines for digitized and born-digital historical, archival, and cultural content.”[1] The BC100, cameras, and software I use in the Digital Imaging Lab ensure that the photos I produce are compliant with FADGI criteria so our viewers can be sure these digital photos are of excellent, professional quality. My photos meet FADGI standards concerning light uniformity and color accuracy to ensure an accurate representation of an object.

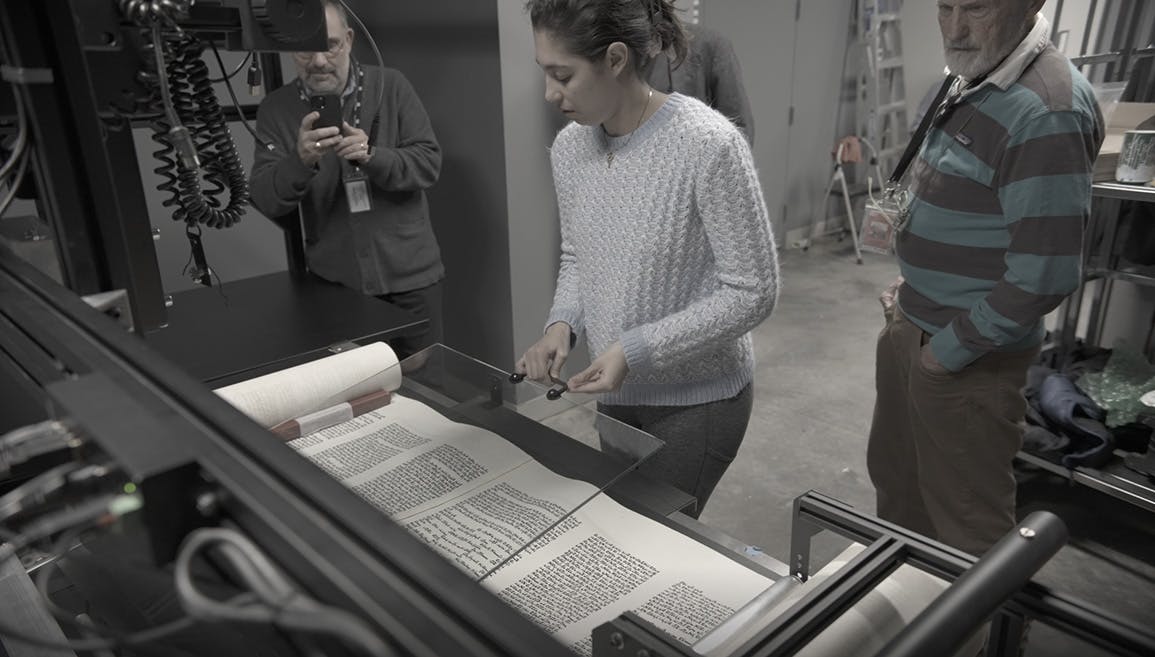

Getting back to the specialized equipment, the lab’s newest acquisition is directly related to the museum’s exciting new venture, the Torah Scroll Project. Museum of the Bible has thousands of scrolls in its collections, the majority being Torah Scrolls. These scrolls range in origin from the twelfth to the twenty-first century and vary from around 30 up to 200 feet in length. Because these scrolls vary in age, size, and condition, I am not able to digitize them in the same uniform quality as bound material with the BC100.

Thus, the Torah Scroll Rig (TSR) was born—or “Esther,” as I like to call her. For the past few years, Museum of the Bible has been working with Michael Phelps of the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library (EMEL) to construct a new type of machine. Utilizing an enormous frame, an overhead camera, and a conveyor belt, the TSR is the first of its kind, made with the sole purpose of unrolling and photographing scrolls with the care and uniformity they deserve.

Figure 1: Constructing the Torah Scroll Rig. Image © Museum of the Bible, 2024. All rights reserved.

After years of correspondence and construction, Esther was installed in early December 2023. The process of installation involved adjusting various components’ ergonomics and reviewing object handling protocols with museum staff.

Figure 2: The Torah Scroll Rig. Image © Museum of the Bible, 2024. All rights reserved.

Figure 3: The Torah Scroll Rig with an unrolled scroll. Image © Museum of the Bible, 2024. All rights reserved.

As the museum’s Digital Imaging Lab grows increasingly robust, I will be constantly documenting protocols and project schedules for years to come. Right now, my focus is on photographing objects, but I hope to one day not just have our collection digitized, but to have the text translated and searchable. Digital preservation is the future of cultural heritage because it overcomes boundaries of accessibility. Thanks to the internet, anyone from anywhere can engage with the Bible through our digital collections at any time. Digital photography is just the beginning.

Watch the videos below to see how the Torah Scroll Rig works:

By Rebeccah Swerdlow, Digital Imaging Specialist

Notes:

1. “Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative.” n.d. www.digitizationguidelines.gov. https://www.digitizationguidelines.gov/.