Rediscovering a Greek Manuscript's Home

At Museum of the Bible, we curators often talk about the provenance of an artifact. Provenance is the chain of ownership from an artifact’s creation to the time the museum acquired it. Ideally, we want to have a complete chain. This is relatively easy to establish with modern objects, but when an artifact is hundreds or thousands of years old, that chain inevitably has missing links. How many gaps and where they fall on a timeline determine whether an artifact has good, acceptable, or bad provenance. Careful detective work can find some of those missing links, but it is rarely possible to find them all.

In my time as a curator at Museum of the Bible, I have uncovered many interesting stories concerning the past owners of our manuscripts. Sometimes a manuscript’s history was troubling, and I wished I could do something about it. In the case of MS.000352, a Greek Gospel book dating to around 1000, I got the chance.

In late October 2019, I exchanged a series of emails with Dr. Greg Paulson, a scholar at the University of Muenster’s Institut für Neutestamentliche Textforschung (INTF). He was looking to update information in the institute’s database concerning the location of several manuscripts identified by what New Testament scholars call a “GA number.” The database is built upon the pioneering work of Caspar René Gregory in the early twentieth century, who devised a system of classifying and numbering all known Greek manuscripts by type of text — papyrus, majuscule, minuscule, and lectionary. In the second half of the twentieth century, Kurt Aland took up Gregory’s work and expanded it, producing two editions of the Kurzgefaßte Liste der griechischen Handschriften des Neuen Testaments (KL) in 1963 and 1994. The database is constantly updated as new manuscripts are discovered and known ones change location. Dr. Paulson was making routine checks about the location of a few manuscripts. After answering his questions, I asked one of my own about a Gospel manuscript in our collections: “By the way, this is MOTB.MS.000352: Is there a GA number for it?” Little did I realize that this was the first step in restoring a century-old loss.

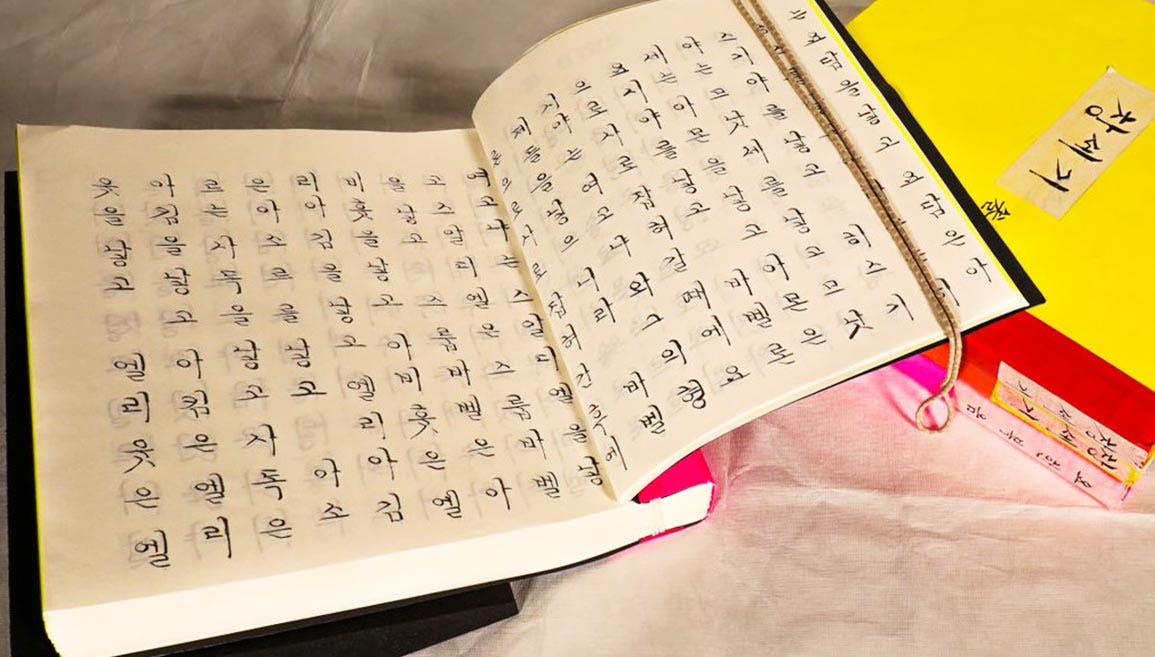

Figure 1: MS.000352 open to the beginning of the Gospel According to Mark on right page. Click here to see more of the manuscript on our Collections page.

Dr. Paulson thought it might have a GA number and asked to see pictures of John 7:53–8:11, the story of the woman caught in adultery known to scholars as the Pericope Adulterae (PA). When I sent him the pictures, I drew his attention to the little red stars at the beginning of each line in the passage and asked if this was typical, because I had not seen them elsewhere. Dr. Paulson replied, “You’re right, it is not typical to mark the PA with stars, which is why I asked for this particular part—it is unique. The MS is GA 1429, which has been missing for many years from Kosinitza. I’m attaching the entry for 1429 in Gregory’s Textkritik, which mentions the stars marking the PA (in German: “Ehebr”).”

Kosinitza! The word practically jumped at me from the page. In March 1917, during the confused fighting on the Macedonian front in World War I, a band of Bulgarian partisans known as komitadji had raided the Theotokos Eikosiphoinissa Monastery (also called Kosinitza) near the town of Drama and looted all its manuscripts. Today, most of the manuscripts are part of a collection in Sofia, Bulgaria. Several manuscripts from the monastery are in library collections in America, and the Greek Orthodox Church was attempting to retrieve them. I alerted our Chief Curatorial Officer, Dr. Jeff Kloha, and began research into the provenance of the manuscript.

The first parts were easy. The information supplied by the dealer, a famous auction house, drew attention to inscriptions in the manuscript that clearly pointed to its origins in a monastery in southern Italy during the eleventh century, when the territory was part of the Byzantine Empire. Later inscriptions, including one in Latin, showed it had remained in Italy for a few centuries. The same source showed it had been in the United States in 1958 when the New York antiquarian book seller H. P. Kraus listed it in a catalog. The description in Gregory’s Textkritik matched the size, layout, and number of folios in MS.000352, and placed it in Kosinitza at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. But was it at the monastery on March 27, 1917? If only there were a clue!

On the inside back cover, someone had written the initials M. K. in red pencil. Since they were above the initials HPK, I thought they could be the initials of a dealer before or after H. P. Kraus. A search for those initials produced no known book dealers. Then the obvious struck me—what if M. K. was a reference to the Monastery of Kosinitza? On a hunch, I used the INTF’s database to search for Kosinitza New Testament manuscripts presently in the Ivan Dujcev Center for Slavo-Byzantine Studies in Sofia, Bulgaria. Thirteen manuscripts contained the initials. Further searching revealed three Kosinitza manuscripts in America the Greek Orthodox Church was asking to be returned (one at the Morgan Library and two at Duke University), and one further manuscript in Uppsala, Sweden, also contained the initials. The growing correlation between the initials and known manuscripts looted from Kosinitza suggested my hunch had been correct.

A long internet search finally produced concrete results. An article by Vasilis Katsaros, “Τρια Λανθάνοντα Χειρογραφα τηςΜονης της Παναγιας Αχειροποιητου του Παγγαιου, της Επονομαζομενης «Κοσινιτσας» ΄η “Εικοσιφοινισσας,” indicated the komitadji had looted another monastery after Kosinitza. One of the group’s leaders, Vladimir Sis, made a catalog to keep the manuscripts straight. In this catalog, he noted those that came from Kosinitza with M. K. or simply K., and those from the monastery of St. John the Forerunner near Serres with M. Cb. Ub. This same Sis is the person who allegedly sold manuscripts from Kosinitza in Germany after the war was over. The initials inside the book established the manuscript was among those looted in Kosinitza on March 27, 1917.

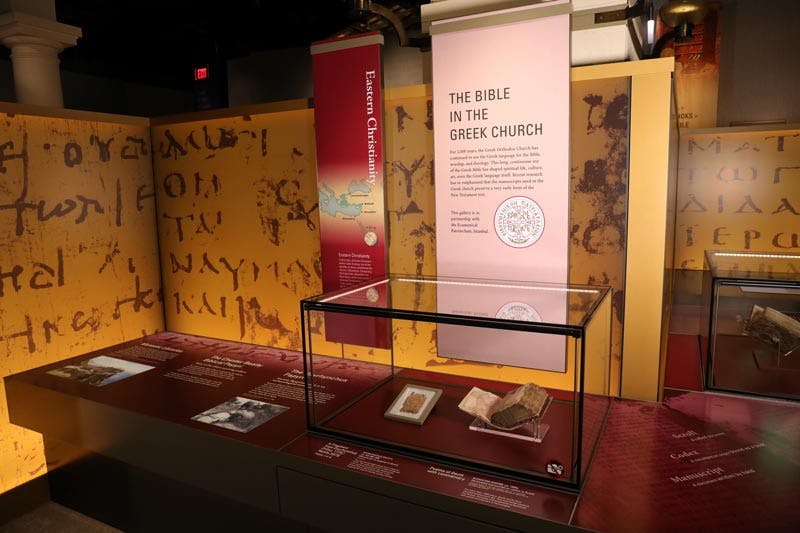

Based on these findings and in keeping with the museum’s Collection Management Policy, Dr. Kloha initiated contact with the Greek Orthodox Church to inform them we had the manuscript and would return it. The museum formally transferred ownership of the manuscript to the Church in June 2020. In September, His All-Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew commended “this apt and honourable decision of the Museum of the Bible.” He gave the museum permission to display the manuscript so “the manuscript’s origins and the history of both it and the other stolen items of the Eikosiphoinissa Monastery may be made known to as many as possible.” The manuscript is now part of a new exhibit on Floor 4 featuring items on loan from the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

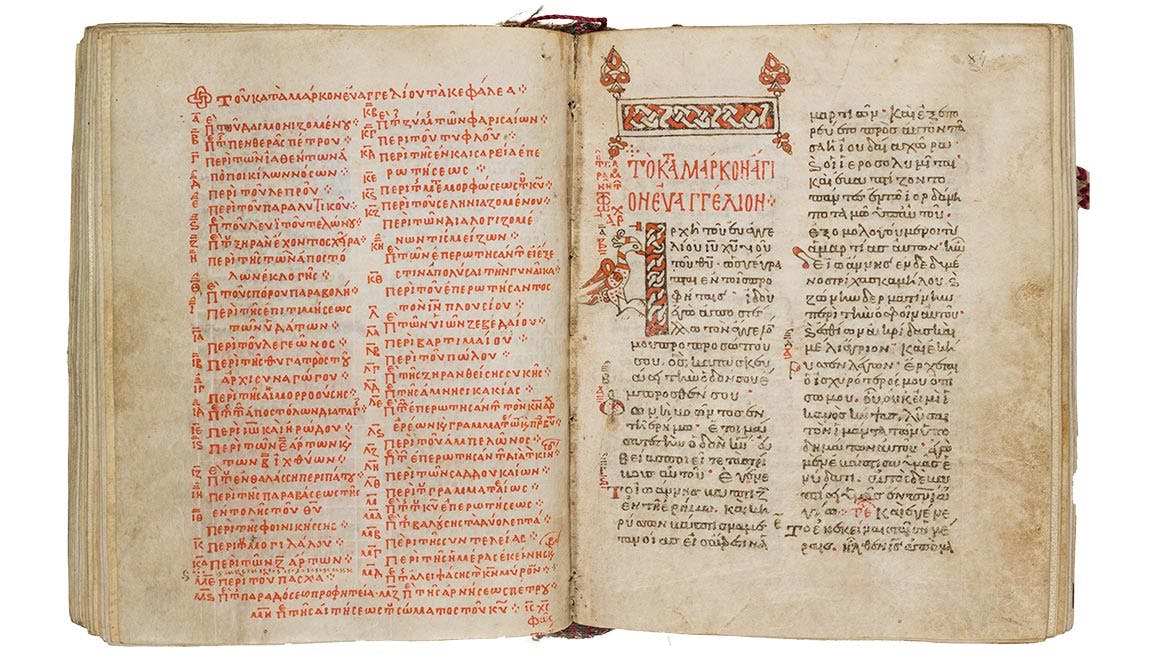

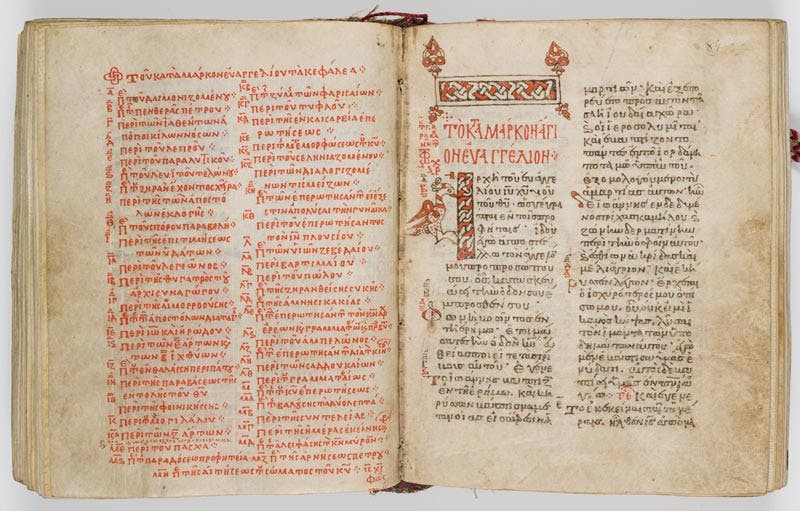

Figure 2: MS.000352 (right) in its new exhibit space near the Psalter (center) from the Holy Monastery of St. Nikanor in Zavorda, Greece on the History of the Bible Floor.

With the approval of the Ecumenical Patriarch, the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America loaned the museum five liturgical objects, and the Holy Monastery of St. Nikanor in Zavorda, Greece, loaned three biblical manuscripts from the eleventh and twelfth centuries: a Psalter, a Gospel lectionary, and a lectionary containing Acts and the Letters of the Apostles. In addition, there is a new mosaic icon of John the Baptist donated to the museum.

Figure 3: Image of the replica of the Icon of St. John the Forerunner donated to Museum of the Bible. The original is in the Patriarchal Church of St. George the Trophy Bearer in Constantinople.

On Monday, October 25, the Apostolic delegation from the Ecumenical Patriarchate visited the museum to bless the exhibit and give thanks for the return of the looted manuscript. You can watch a video of their visit here.

To see a more detailed version of this article, click here.