From the Podcast: Dr. Chris Jones and the “Wicked” Bible

Recently, on our podcast, Today at Museum of the Bible, Chief Curatorial Officer Dr. Jeff Kloha interviewed Professor Chris Jones.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and space. To listen to the whole interview, check it out on our podcast, Today at Museum of the Bible.

Jeff Kloha: Welcome to Today at Museum of the Bible with Chris Jones, a professor of medieval history at the University of Canterbury.

Chris Jones: Jeff, thank you.

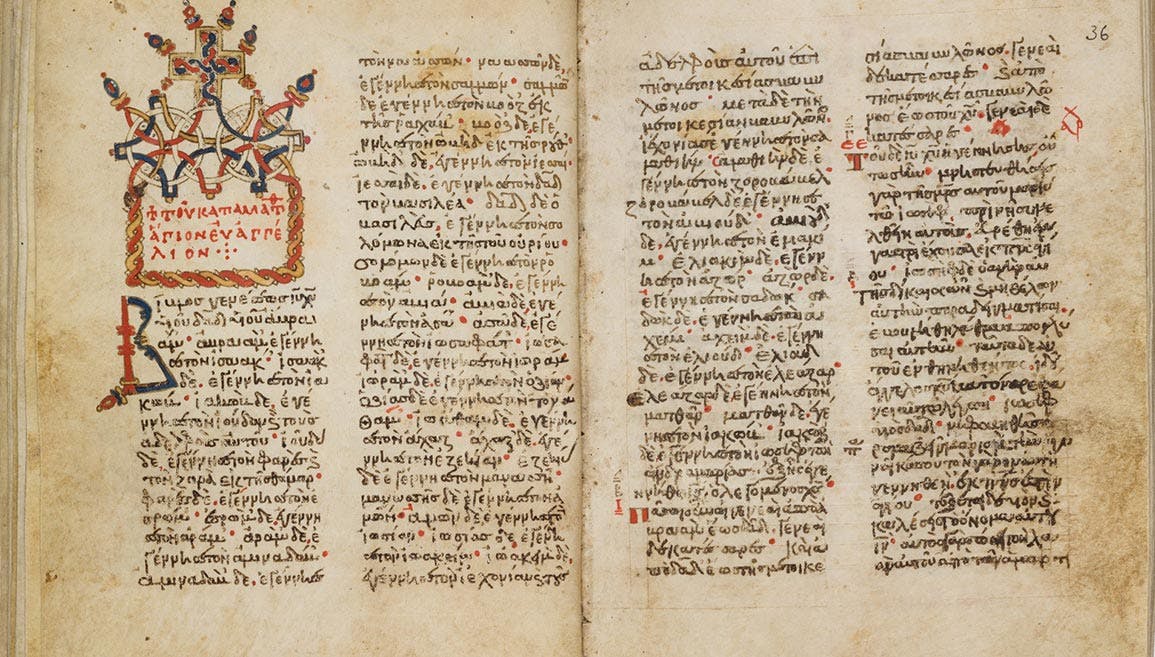

Jeff: Professor Jones has come all the way from New Zealand to look at a couple of our Bibles, and you’ve become a bit of a specialist on this particular Bible. So, what has gotten you to Museum of the Bible today?

Chris: So first, let me say that it's wonderful to look at the collection. I came to look at this particular type of Bible as a result of pure happenstance in some ways. Two or three years ago, I had a student who claimed to have a very unique Bible. This turned out to be an extraordinarily rare 1631 "Wicked" Bible, termed as such because, in Exodus 20, the commandment that should read, “Thou shalt not commit adultery,” instead reads, “Thou shalt commit adultery.”

Jeff: Very famous, well-known misprint in the Bible.

Chris: Absolutely. The first question my student asked was, is this really what it appears to be? And it was. But the next question was, how many of these are there? How rare is it? I quickly discovered this is a hard question to answer. Some say five or six. Some say as many as 50. So, the first project was simply answering the question, how many are there? That’s what’s led me to the museum today.

Jeff: So, you've been on a worldwide search for “Wicked” Bibles?

Chris: I have been. Prior to the pandemic, I spent my time in the British Isles, and I was looking at copies in all the places you expect: British Library, Oxford, and Cambridge. Trinity College, Dublin, has a copy, too. York Minster has a copy tucked away, and Glasgow has a copy. My next step was to come to North America. So, that's what's brought me to Museum of the Bible, which, quite uniquely, has two copies.

Jeff: Well, and this is actually news, we have had a “Wicked” Bible displayed off and on since we opened in 2017, but recently, we've uncovered a second “Wicked” Bible.

Chris: I was looking at it yesterday and today, and it's absolutely fascinating. It's a very good copy of the “Wicked” Bible. I think probably a little bit earlier in the print run than the copy you've had on display. Also, a little bit more complete than that copy, printed on better paper.

Jeff: My understanding from you is we are the only institution that has two copies of the “Wicked” Bible.

Chris: This is absolutely the case.

Jeff: So how many copies are there, based on your research so far?

Chris: So far there are 17 copies in institutional hands and in private hands somewhere between four and eight. But there's a lot of variety within those copies. And that has produced, as all good research does, a whole series of new questions.

Jeff: So, tell us the story. Let's go back to 1631, Robert Barker, and what's his position? Why is he printing Bibles?

Chris: Well, he's basically inherited the king’s license to print Bibles, so he is the official printer. He holds a monopoly on printing the King James Bible. And as part of this, he’s very successfully produced the first print run, the great folio editions that King James was very keen to commission. This is something that’s produced as a result of the Hampton Court Conference and is known as the King James Version 1611. Now, jump forward some 20 years and Barker still holds the license. Now he's producing much smaller octavo copies, roughly the size of a modern paperback, for the average household. His career is not going quite as well financially as it did for his father when he held the license.

Barker was underestimating the market and making a number of misjudgments. The way he deals with this is to make cutbacks wherever he can. So, there are quality control issues. These issues come to a head in the case of our "Wicked" Bible. If Barker had been lucky, no one would have noticed. But unfortunately, someone notices this particular misprint and another misprint is equally adventurous. It's in the book of Deuteronomy, 5:24. It should talk about the greatness of the Lord. But in this particular case, it talks about the “great ass” of the Lord, which, I'm going to hasten to say, is probably not as blasphemous as it is for us today.

Jeff: The different connotations of that term today.

Chris: Yeah. We're talking in the seventeenth century in terms of the animal.

But someone notices and draws these issues to the attention of the Court of High Commission, which basically deals with printers in this period. Barker is very familiar with it. He prosecuted a lot of people there for basically breaching his monopoly. And what comes out in the case is he used the worst possible paper. And you can see this in copies of the "Wicked" Bible. These look tatty by comparison to many sixteenth-century Bibles, even to Barker's earlier works. And that's not the result of time and that's not the result of poor upkeep. That's because they're genuinely bad.

I was looking at one this morning where the print has gone sideways at one point. Absolutely nothing has been done about this except it's been bound very quickly and put in the book, and hopefully no one will see it. The remarkable thing about "Wicked" Bibles is the more you look at them, the more errors you spot. And very few of them are as striking as missing key elements of a commandment. But they are there. Genesis 23, for example. You read Genesis 23 and then you find yourself going on to read Genesis 23 again because no one has bothered to change it to 24.

The outcome of this is Barker is fined, but not particularly heavily. He's fined about £200. His colleague who he's printing with, Martin Lucas, is fined another £100. So, £300 in total. He never pays it.

Jeff: Of course.

Chris: The interesting thing about this case, unlike many in the Court of High Commission, the court records actually survive. We can see what happens. Barker goes into court and says, there shouldn't be a hearing at all. It wasn't my fault. It was the workman. He manages to drag this court case out for pretty much an entire year. Eventually, the king intervenes, and Barker is offered a deal. And the deal Barker is offered is Barker will go and set up a Greek printing press and print works by one of the king's favorite theologians. And if Barker will go and do this and print at least one work a year, the fine is waived. So, from the king's perspective, this becomes leverage. And Barker's instant response to this is absolutely, of course. Three years later, he's still saying I'm going to do this, but I haven't done it yet, but I will do it.

Jeff: Did he ever print any?

Chris: He does print one or two works in Greek, eventually. But three years after the court case, he's still being sent reminders. But now the king's advocate is on his side, asking the court to remit the fine. So, Barker deals with this very shrewdly, I have to say. In the end, he ends up in jail, but for something completely different. But it's a very, very interesting case, and all of that draws this "Wicked" Bible to popular attention. And interestingly, it then disappears from view, and a lot of rumors start to circulate around it. And at the beginning of the nineteenth century, people assumed it might even be a myth. And then actually in London, one is found by Henry Stevens, an American in London collecting for the New York Public Library. We have a wonderful account of these memoirs, you can type “Stevens” into Google Books and find it.

Jeff: Is he looking for a “Wicked” Bible or does someone show him one?

Chris: Stevens manages to get hold of a copy, then establishes that it's octavo, that it's 1631. That copy is now in the New York Public Library. It's the first discovery. It's not, though, the most fascinating part of the story. Stevens goes back to his lodgings, where he has a number of Bibles he's been collecting. And in his notes, he says, “I found another one on the shelf in the Bibles I already owned.” He's also the man who gives it the name the “Wicked” Bible.

Since Stephens, in the course of the nineteenth century, another six of these turn up. Some questions, though, that arise from this is how many copies were printed and what happened to the copies? And unfortunately, Stevens, who is a good collector, gets a little bit carried away, and he sort of claims all of these copies were destroyed. It turns out this isn't the case at all. What the court ordered was that all the books be collected and returned to Barker, corrected, and sold. This seems to be what happened. It just seems to be that many of them are not actually corrected.

Jeff: So how did they make the correction physically? Did somebody take a pen and write "not" above the line? Or did they do a cancel page?

Chris: It's pretty much the first option. We've got traces actually, and it's even worse than in some cases. In the Canterbury copy, literally, they seem to have stuck a piece of paper in and the piece of paper has come away, but the glue marks have not. But for the cases of the “great ass” Bible, and I’ve found three of these so far, they just ink blot. It's done in the cheapest possible way, but how many of them they produced we're very uncertain about.

Jeff: Even the court records don’t mention a number in the print run?

Chris: The court records don't give us a number. I think it's much more likely that we're looking at a thousand copies, probably printed in 1631. But there's a lot of variation within those copies. That’s part of this project, which has led me to look at the way these Bibles were printed, look at the way they are assembled.

Jeff: How much longer do you think you'll be on this project?

Chris: The longer I've worked on it, the more things have developed. My first stopping point is to produce the catalog outlining where all these so-called “Wicked” Bibles are. And I'd like to publish a little around the question of the publishing industry in this period. When we tend to look at seventeenth-century printing, I think we've simplified the picture slightly. I think it's telling us that the Bible is very central to the culture of seventeenth-century England, but it's also telling us about the attitude of people in that culture to the Bible. And I think for people like Barker, they're not really approaching it from a religious perspective. It's all about commerce.

Jeff: It's a fascinating topic. Well, Chris, it's been great to chat, and I wish you the best in your research and look forward to seeing the results.

Chris: Thank you so much, Jeff.