Beyond the Walls: Witnessing the Passion

Beyond the Walls follows a photographer, a curator, and an editor outside Museum of the Bible in their search for the Bible’s influence in the nation’s capital.

Holy Week is a bit more than a fortnight away. This holy season is a time for many to reflect on the final events of Jesus’s life, from the Last Supper through his resurrection. The last days of Jesus’s life are told in each of the four Gospels. Though details differ among these, each tell the same story, of the suffering of one man ending with salvation for all.

For almost two millennia, Christians have commemorated Jesus’s final acts. The rituals and observances performed by so many — from Ash Wednesday through Easter Sunday — are one way of commemoration. Another is through the arts. In paintings and passion plays, sculptures and symphonies, icons and altarpieces, Christian artists have strived to capture every moment of Jesus’s life, especially the events of the passion and the power of the resurrection.

Some of these beautiful works of art can be found here in DC, in the stunning cathedrals and churches, as well as in universities and museums. As one would expect, one of the largest collections is found in the National Gallery of Art. For Christmas, we ventured to the Gallery to take in all the artworks depicting Jesus’s birth. As we promised, the team returned to the National Gallery in anticipation of Holy Week and Easter.

Instead of trying to canvass the entire collection of art related to Jesus’s passion and resurrection (a monumental task, as we discovered last time), this time the team focused on a few pieces that most appealed to us.

One piece, from the late fifteenth century, combines the events of Holy Week, leading up to the moment before Easter, and even connects them to other moments in Jesus’s life. The oil painting is simply titled Calvary, and the artist is known only as the Master of the Death of Saint Nicholas of Münster.

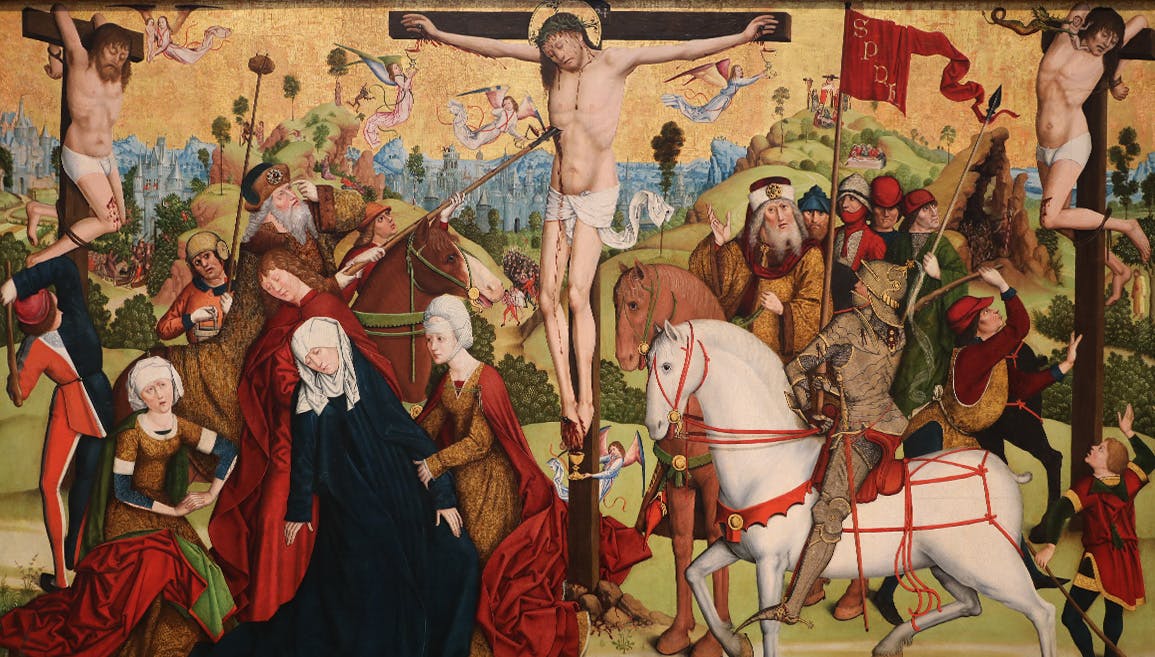

Figure 1: Master of the Death of Saint Nicholas of Münster, Calvary, oil on panel, ca. 1470/1480.

As you can see, the crucifixion dominates the composition. Jesus’s sacrifice is central here; the resurrection is not shown. However, the painting contextualizes the crucifixion with multiple scenes in the background from before, leading up to, and following Jesus’s death. The events of Holy Week proceed from left to right in the painting.

The first is Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. Jesus sits astride a donkey as eager Jerusalemites lay down cloaks and wave what the artist intends to be palm branches. Citizens even populate the trees flanking the road and can be seen in the windows above Jerusalem’s gate welcoming Jesus’s entry.

Figure 2: Detail of the triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem in Calvary by the Master of the Death of Saint Nicholas of Münster.

To the right of this is an interesting combination of two stories: Jesus’s agony in Gethsemane and the temptation of Jesus by the devil during his time in the wilderness. The inspiration for combining these stories seems to be the moment when Jesus, in somber prayer, asks if the cup of his suffering and death can pass from him. While in the biblical text the request is followed immediately by, “yet not what I want but what you want,” this moment gives the artist an opening to imagine what else Jesus might have felt, thought, and said in those agonizing moments. For the artist, this comes in the form of temptation or of remembering when Jesus was tempted in the wilderness to do what he wanted, not what God wanted of him.

Figure 3: Detail of Jesus’s agony in the garden of Gethsemane and Jesus’s temptation in the wilderness after his baptism in Calvary by the Master of the Death of Saint Nicholas of Münster.

Thus, we see Jesus praying in the garden, the disciples asleep behind him, an angel on the hill before him holding the cup Jesus asks his father to pass from him. Behind the angel are the three scenes of Jesus’s temptation, set in the order found in the Gospel of Luke. On the bend winding up the hill, the devil tempts Jesus to turn stones to bread, at the top, he tempts Jesus with the glory of the “kingdoms of the world,” and a little further to the right, Satan and Jesus stand at the top of what is meant to be the temple, the third and final temptation. In the center of this miniature scene comes Judas Iscariot — clutching his red sack of silver — leading a group of soldiers toward Christ.

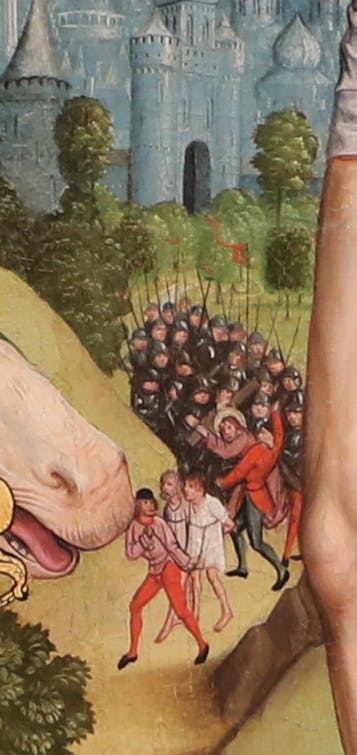

Four more scenes complete Jesus’s story, bringing what is in the background forward to the central scene of the crucifixion before returning to the background and the events that followed Jesus’s death. The first is Jesus carrying his cross, the two thieves are led before him, a man has his arm raised to whip Christ, and a host of soldiers follows behind; there is no sign of Simon the Cyrene. The road leads to the primary focus of the composition, the crucifixion in the foreground, bringing the painting’s two levels together.

Figure 4: Detail of Jesus carrying his cross as he and the two thieves are led to the place of crucifixion in Calvary by the Master of the Death of Saint Nicholas in Münster.

The artist’s depiction of the crucifixion brings together elements from the Gospel accounts, with some additions making visible what in the Bible is expressed only in words. For example, the two thieves hanging to either side of Jesus show the artist used the verse from Luke where one of the thieves defends Jesus’s innocence and asks to be taken to Paradise. Look closely, the thief on Jesus’s right hand has a small angel hovering near his mouth, holding his soul, the smaller human with hands folded in prayer. The soul of the thief on Jesus’s left hand is also visible, but is being snatched by a demonic creature as punishment.

Figure 5: Master of the Death of Saint Nicholas of Münster, Calvary, oil on panel, ca. 1470/1480.

At the base of the cross, in the left foreground, Mary swoons, being held up by the disciple “whom [Jesus] loved,” associated with John the Evangelist, and a woman, likely Mary Magdalene. The woman to Mary’s right proper is likely the other Mary or Salome. The inclusion of the male disciple comes from the Gospel of John, as does the scene of the soldiers breaking the legs of the thieves with clubs — a detail found only in John’s Gospel — even as two soldiers stab Jesus with a spear.

Finally, some elements of church tradition and theology are present. Most noticeable are the four small angels with cups collecting Jesus’s blood as it flows from each of his wounds, an image tied to stories of the Holy Grail as well as showing the purity of Jesus — the blood of the Son of God is too pure for this world.

For the final three scenes, we again retreat to the background. Just behind Jesus, to his left proper, is the deposition of Jesus from the cross and his burial. The six characters present are the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and Salome, and “the disciple [Jesus] loved,” Joseph of Arimathea, and Nicodemus.

Figure 6: Detail of Jesus's deposition from the cross and his burial in Calvary by the Master of the Death of Saint Nicholas in Münster.

This scene flows down the hill into the next, where Jesus now stands triumphant at the Hellmouth, conquering death, the devil, and retrieving the souls of the saints who lived and died before his sacrifice.

Figure 7: Detail of the "Harrowing of Hell," when Jesus saves the saints who died before his sacrificial act, in Calvary by the Master of the Death of Saint Nicholas of Münster.

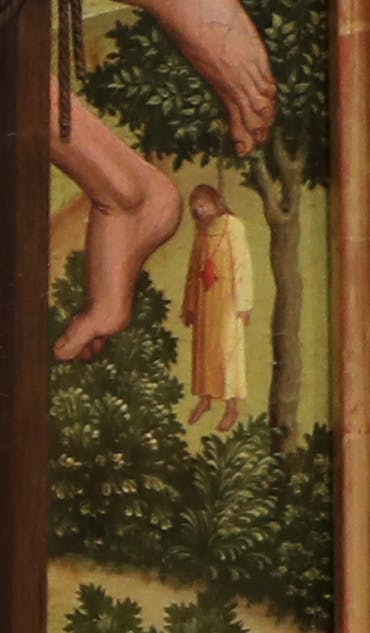

The painting concludes, in the background, on the far right, with Judas Iscariot hanging from a tree. Judas’s scarlet money bag hangs around his neck, contrary to the biblical accounts, but in such a way that both identifies the nature of his crime and perhaps also, due to its color, alludes to the bursting open of Judas’s guts as told in the book of Acts.

Figure 8: Detail of the death of Judas in Calvary by the Master of the Death of Saint Nicholas in Münster.

This painting of Holy Week brings the viewer to the very moment before the resurrection on Easter morning. It contextualizes and enriches the stories in the Gospels, adding details and depicting actions not in the biblical text that, taken together, create a powerful meditation on Jesus’s final week and the sacrifice of the crucifixion.

Several of these same scenes are also captured in a triptych by Andrea di Vanni, created about a century earlier, and a pentaptych (not to be confused with the Pentateuch) from the mid-fifteenth century by Benvenuto di Giovanni. Both series begin with the agony of Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane, both end with Jesus standing triumphant over death, the devil, and the “gates of Hades.”

Figure 9: Andrea di Vanni, Scenes from the Passion of Christ: The Agony in the Garden, the Crucifixion, and the Descent into Limbo, tempera on panel, 1380s. Though the title reads the descent into limbo for the third panel, the inscription held by God the Father above reads, “Destruxit quidam mortes inferni / et subvertit potentias diaboli” (He destroyed the deaths of hell / and overturned the powers of the devil) See the endnote for more on “limbo” and the harrowing of hell.

Figure 10: Benvenuto di Giovanni, The Agony in the Garden, Christ Carrying the Cross, the Crucifixion, Christ in Limbo, the Resurrection, tempera on panel, probably 1491.

These multi-scene, multi-panel paintings allow viewers to gain a glimpse of Jesus’s passion, crucifixion, and triumph over death. As such, they parallel the Bible by telling a story, albeit not always exactly the story told in the different Gospels. Other works of art, conversely, focus on a single scene, even a single moment of the passion. Some of these images can be overwhelming.

Lamentation, painted by Andrea Solario at the beginning of the sixteenth century, shows the immense grief of those who surround Christ’s dead body. The artist has even painted the individual tears shed by the mourners.

Figure 11: Andrea Solario, Lamentation, oil on panel, ca. 1505–1507.

Figure 12: Detail of the Virgin Mary's face, with tears streaming down her cheeks. Each of the characters has tears flowing down their faces.

Jesus’s death is especially powerful when sculpted in the round. Scenes of the pietà — Mary’s pity and grief over the loss of her son — were common. Michelangelo’s Pietà is the most famous today, a facsimile of which you can see at Museum of the Bible, but this piece by Giovanni della Robbia captures the moment more viscerally.

Figure 13: Giovanni della Robbia, Pietà, glazed and painted terra cotta, ca. 1510/1520.

While in Michelangelo’s Pietà, Mary sits composed, even slightly reclined, here she is almost standing, holding the body of her son, her back bent as she looks down on his lifeless form. Mary’s lips, it appears, are slightly opened, her face cast in loss and grief. The use of terra cotta in della Robbia’s Pietà contrasts with the smooth marble used in Michelangelo’s, bringing more grit to the former. In these works, the ultimate sacrifice of Jesus is the only focus. Easter and the resurrection are still far off; the triumphant feeling of their victory is not yet felt. Viewers are left, like Mary, with only grief.

But, as we know from the biblical text, Easter morning arrives and with it the triumph of Christ over the wages of sin. As Easter approaches, we hope some of these works will stir you to come see them yourself — they are more potent in person — as you explore the Bible’s presence throughout DC. While visiting, stop by Museum of the Bible for more experiences focused on Easter. Our new exhibit on the Shroud of Turin lets guests see how the descriptions of Jesus’s suffering in the biblical text match the wounds of the man of the Shroud and encourages reflection on the many acts of pilgrimage Christians have undertaken to visit the sites connected with Jesus’s life, passion, and resurrection. Or contemplate the magnificent stained glass window of Easter morning by famous designer Louis Comfort Tiffany. The serenity of Jesus’s expression and posture stand in stark contrast to the suffering depicted in scenes of the passion and crucifixion. Or take a look at everything we have online to commemorate the Easter season, including a video presentation of the Stations of the Cross with Jeff Cavins. No matter how you celebrate, Museum of the Bible is here to enrich your Easter.

Until our next venture beyond the walls, we wish you a happy Easter.