Who Are “the Maccabees”?

For the Jewish community, Hanukkah just ended. It ran from the evening of December 18 until sunset on December 25—eight days.

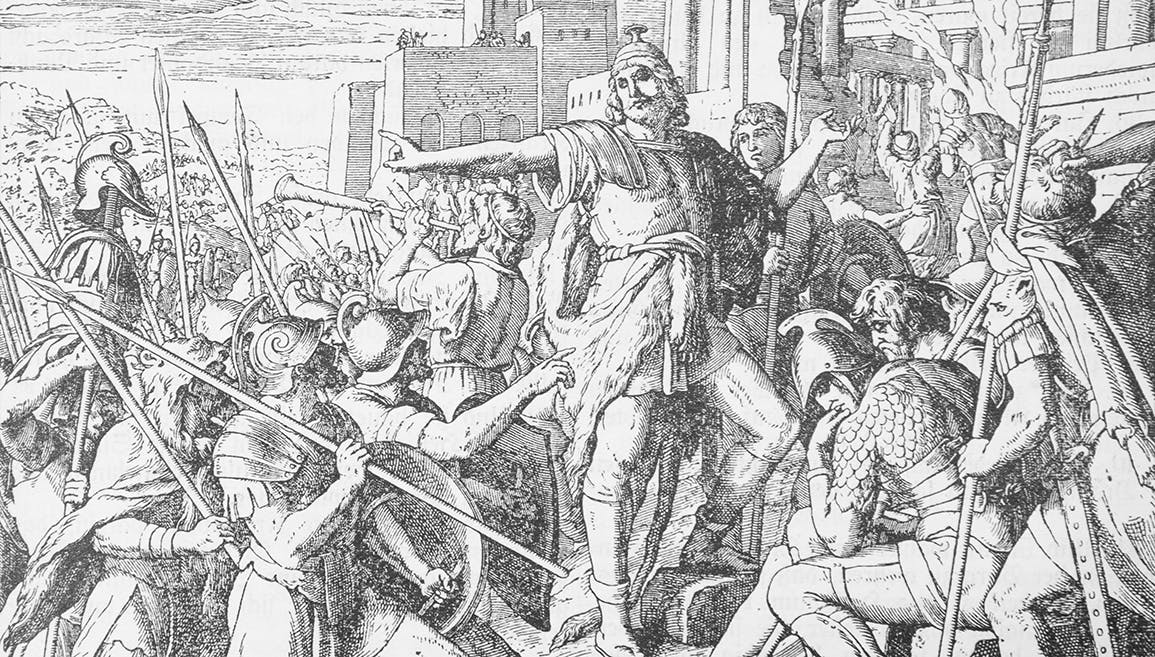

The story of Hanukkah is a complex one, involving internal Judean conflict that eventually resulted in Antiochus IV forbidding many Jewish religious practices and taking over the Jerusalem temple, desecrating it. Hanukkah celebrates the success of the revolt led by the priestly family of Mattathias and his sons, including Judah “Maccabee,” against Antiochus. The etymology of the nickname “Maccabee” is uncertain, though some trace it to the Hebrew word for “hammer.” However, in popular Jewish tradition today, the entire group of rebels is known by Judah’s nickname, “the Maccabees.”

But who exactly are “the Maccabees”? The answer might depend on who you are. In the Jewish tradition, the sobriquet Maccabee always refers to Judah Maccabee and his brothers, the leaders of the rebellion against Antiochus IV. But in a number of Christian traditions, “the Maccabees” frequently refers to a particular woman and her seven sons, whose martyrdom in the face of Antiochus’s persecution appears in 2 Maccabees 7.

The most significant reason for this difference is because the books of Maccabees are not part of the Jewish biblical canon. Originally written by Jews, these books were only transmitted by Christians in Greek as a part of the Old Testament Apocrypha for much of history. The Hebrew originals are lost and were generally not read by Jews. Instead, Jews told the story of the Maccabean revolt through other texts and in different ways, including a rabbinic text called Megilat Ta’anit and the Babylonian Talmud. Though the story of the woman and her seven sons is recounted in the Babylonian Talmud, it has been transposed from the period of Seleucid persecution to a later period of Roman persecution, with the evil king generically named “Caesar” rather than Antiochus. In the Christian tradition, meanwhile, because of the continued reception of the books of Maccabees, the martyrs are always associated with the Maccabean revolt, and they become known as the primary “Maccabees” by the fourth century AD.

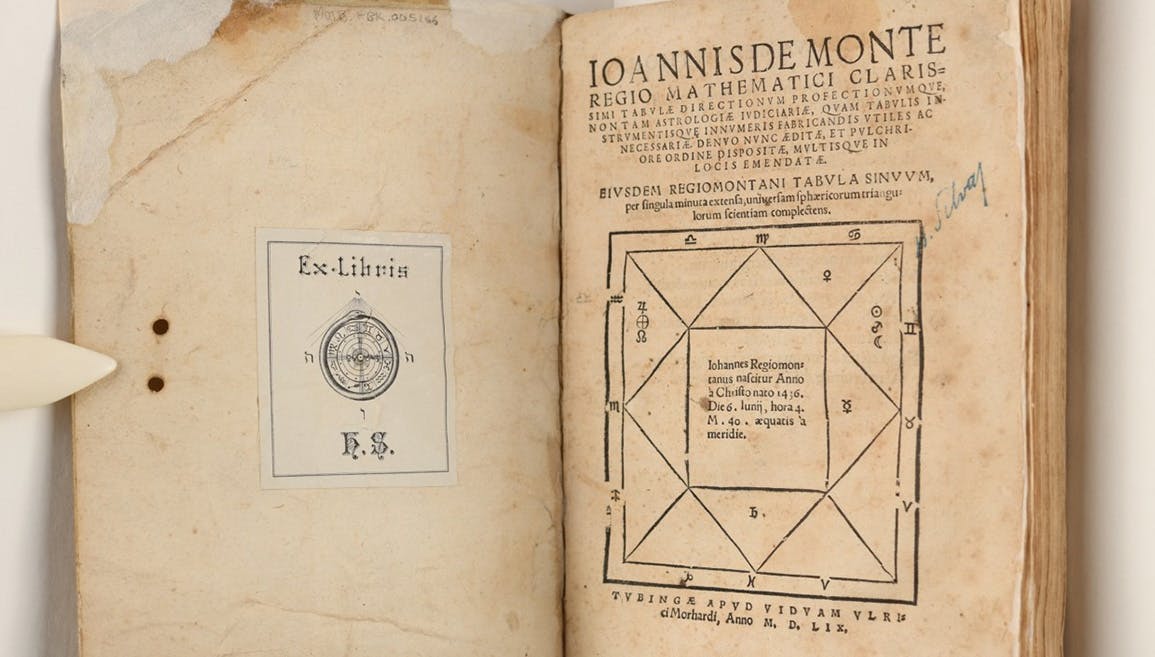

Figure 1: Dick Vellert, Martyrdom of the Seven Maccabee Brothers and Their Mother, ca. 1530–35. Public domain.

For the church fathers, “the Maccabees” became significant as a paradigm for Christian martyrdom. Like much of Christian interpretation of the Old Testament and the Apocrypha, the Maccabean martyrs were read typologically, prefiguring future Christian martyrs. Even when not read in this way, the characters of 2 Maccabees 7 were understood as role models for Christian martyrs. Origen and Cyprian, for example, both understand the story in this way. In Origen’s Exhortation to Martyrs, they are the prime biblical example of proper martyrdom.

Figure 2: Antonio Ciseri's Martyrdom of the Seven Maccabees (1863), depicts the woman with her dead sons. Public domain.

In their retelling of the story of the Maccabees, on the other hand, Jews focused on a completely different story, one first attested in the Babylonian Talmud. This story tells that when the temple was recaptured from Antiochus IV after the Hasmonean victory, it was to be rededicated to the worship of God. However, there was only sufficient pure oil to light the temple candelabrum for one day; it would take eight days to procure more oil. Miraculously, the oil lasted the whole time, allowing the priests to purify more oil. Thus, Hanukkah is celebrated for eight days. In focusing on that miracle, the Talmud centers the holiday neither on the sacrifice of the martyrs nor on the Hasmonean victory, but on the purpose of the revolt: the restoration of the worship of God following the dictates of the Torah and the hand of the divine making it possible.

Figure 3: Image of the Maccabees from the Knesset (Israeli Parliament) Menorah, Jerusalem. Public domain.

Jews continue to celebrate the Hasmoneans’ victory every year on Hanukkah, despite the absence of the books of Maccabees from the Jewish Bible. Meanwhile, some Christian churches, such as the Roman Catholic Church and most Orthodox churches, celebrate the feast day of the Maccabean martyrs on August 1 and read 2 Maccabees 7 as a part of their liturgy. Both communities find things to learn from “the Maccabees.”

By Jesse Abelman, Curator of Judaica and Hebraica