Visualizing Christmas: The Nativity Cribs of Malta and Gozo

What do a sleeping boy and a climbing shepherd have to do with Christmas? Around the world, one of the ways Christians celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ is by placing a Nativity scene in their homes or front yards. Whether in Germany, Peru, or Spain, Nativity scenes depict the Holy Family, the shepherds and sheep, the wise men and camels, and the angels and the star. The people of Malta, a nation of islands in the Mediterranean Sea, have developed distinct traditions to celebrate Christmas. Among the most beautiful is building Nativity “crib” scenes with all the traditional figures—and a few others to help tell the meaning of the story.

The history of Nativity crib building traces back to the thirteenth century, when St. Francis of Assisi staged a “live” Nativity scene, complete with animals, at Greccio in central Italy. He based this on the manger scene he saw during a pilgrimage to Bethlehem in the Holy Land. Over the next centuries, the building of cribs with movable figures spread to Poland, Spain, Germany, and throughout Europe in homes, churches, and village markets. On the islands of Malta and Gozo, nativities were first introduced in the early 1600s, with the oldest surviving crib dating to 1670. In the centuries since, building Nativity cribs has become not only an art form—it’s become competitive!

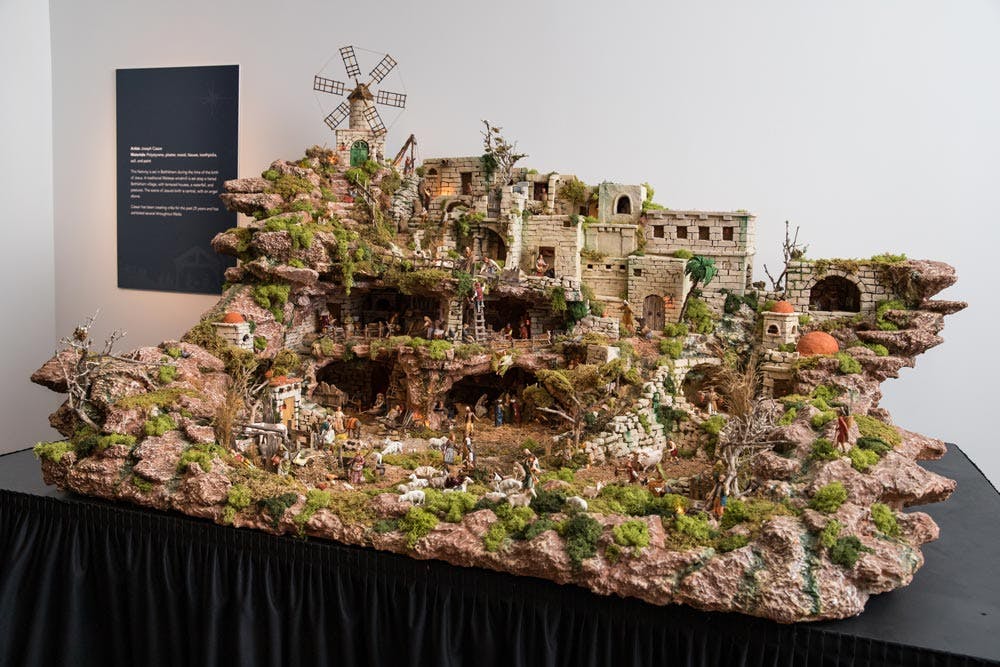

Figure 1: Elaborate crib by Joseph Cassar.

Modern competitive crib-building in Malta began in the 1950s. A Christian organization in Malta (called M.U.S.E.U.M.) first distributed small Nativity kits to every child. As a result, more than 20,000 children would learn the Christmas story and assemble and decorate a Nativity crib or a bambino, a small statue of the infant Jesus on a papier-mâché rock. Just before Christmas, each town would hold a novena, a gathering for singing, prayer, and Scripture reading in the nine days leading up to Christmas. During this festive event, the children’s cribs and bambini would be awarded prizes. Over the years, the interest and skills fostered by these activities led to the formation of local clubs dedicated to building cribs and the organizing of contests to award prizes and recognize the best examples.

Museum of the Bible is hosting an exhibition of the winning cribs from a contest sponsored by the nation’s Ministry for the National Heritage, the Arts, and Local Government. These cribs, each approximately four feet square, are beautiful examples of this tradition. You can view images of these cribs and watch video of the artists explaining their work on the museum’s website—they truly must be seen to be appreciated.

Some are set among traditional buildings and scenery in Malta and Gozo, including stone pillars topped by crosses (which dot Malta and Gozo), plants and fish native to the islands, and depictions of religious statues and sculptures found in the villages.

Figure 2: Note the cross-topped pillar, left, in this crib by Raymond Deguara.

One crib is set in a house that was partially demolished during the horrific, sustained bombing the islands suffered during the Second World War. While it may seem out of place to see the Holy Family, shepherds, and angels among the buildings and scenes of Malta, these cribs are visual reminders of the Bible’s description of Jesus as the Son of God, the “word who became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory” (John 1:14).

The Holy Family, set among Maltese scenes of daily life, a reminder of Jesus dwelling among us.

Figure 3: The Holy Family in the crib by Adrian Gatt.

Figure 4: The Holy Family in the crib by Brian Cachia.

Figure 5: The Holy Family in the crib by Raymond Deguara.

Figure 6: The Holy Family in the crib by Jennings Falzon.

Figure 7: The Holy Family in the crib by Keith Galea.

Figure 8: The Holy Family in the crib by Alexander Powell.

Unique to Maltese cribs are the figurines, called pasturi. Over the centuries, special significance has been attached to individual figures to help tell the Christmas story. For example, a “sleeping boy” symbolizes people who do not understand the significance of the birth of the Savior.

Figure 9: The "sleeping boy" in the crib by Joseph Cassar.

A “kneeling shepherd” symbolizes the worship and devotion that should be given to the Christ.Other figurines depict people whom Jesus came to help. Unique to the Maltese crib tradition, a dove is sometimes present, symbolizing the Holy Spirit. And, camels, which are commonly associated with the magi, are not found in Maltese cribs—but cattle, donkeys, and sheep are always there. Musicians are almost always depicted, too, symbolizing the joy and celebration of Jesus’s birth. The quality of the pasturi is a major element in judging the winning crib in competitions.

Figure 10: Musicians symbolize the celebration of Jesus's birth; in the background a woman walks wearing a traditional għonella. Pasturi by Jesmond Micallef in the crib by Adrian Gatt.

Figure 11: Musicians in the crib by Ramond Deguara.

The winning crib in the Museum of the Bible exhibition was created by Adrian Gatt and Raymond Zammit, with the pasturi by Jesmond Micallef. This Nativity is set in a Maltese house partly demolished during the Second World War. Around the scene, musicians play traditional Maltese instruments, while a woman in traditional dress (għonella) walks with her daughter. You can see this crib and hear Mr. Gatt describe its features in the video below. This crib is now a part of the permanent collection at Museum of the Bible, to be enjoyed by our guests.

The Malta and Gozitan Nativity cribs are on display until February 2.