Moses Gaster and the Samaritans: Separated by a Common Language

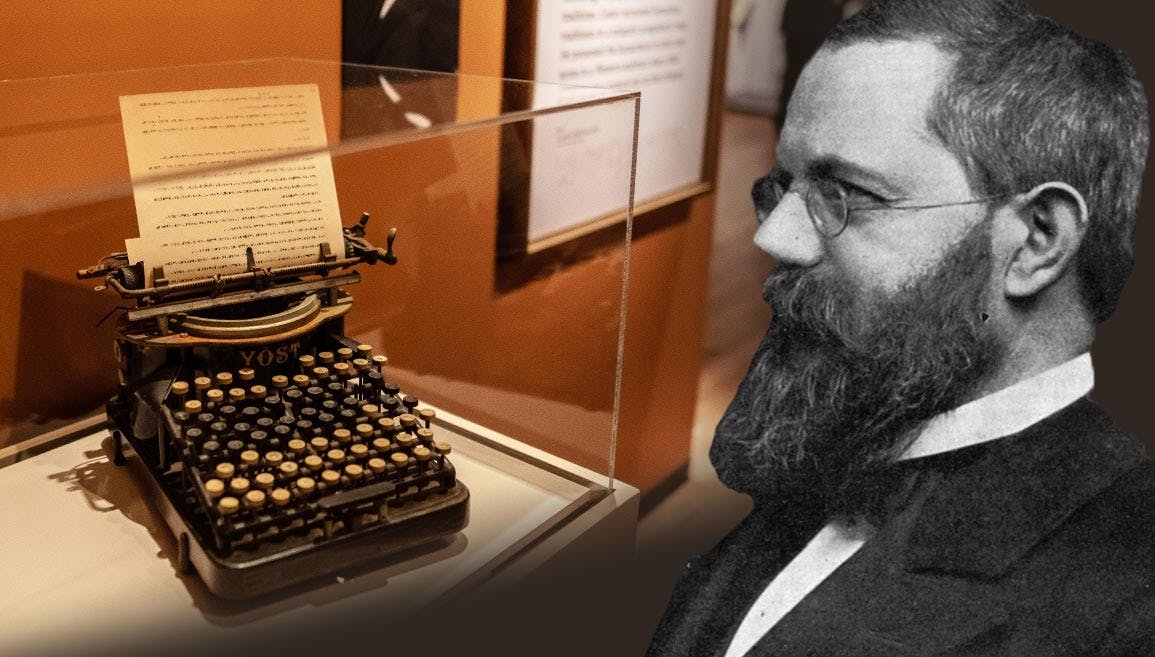

If you walk into Museum of the Bible’s new exhibition, The Samaritans: A Biblical People, and follow the wall on the right, tucked into a corner toward the back of the gallery is a worn Yost typewriter. The carriage bears some rust, and the manufacturer’s name, painted below the carriage in large, stylized letters, is fading, as are the letters on the keys. But if you take a closer look at the keys, you’ll notice — these are not the letters of the English alphabet — but the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. However, the typescript held in the carriage isn’t written in the Hebrew alphabet used by Jews. It is in Samaritan Hebrew, which descended from the ancient paleo-Hebrew script and is distinct from the Aramaic script brought by the Jews from Babylonia after the exile.

Figure 1: The title wall of the exhibit, The Samaritans: A Biblical People. Photo copyright Museum of the Bible 2022.

The typewriter was custom made by Moses Gaster (1856–1939), a scholar and rabbi, so he could correspond with Samaritans in Palestine, to learn about their community and their culture. The Samaritans are a micro-community of around 860 people who see themselves as the last remnant of the Israelite tribes of Ephraim, Manasseh, and Levi, who were never exiled from the land of Israel. Gaster could not write in Samaritan script, and the Samaritans could not read his Jewish script, so he had the typewriter built as a way to reach out to them. This typewriter is emblematic of the way Gaster approached his scholarship, as a means to connect to other humans and understand them on their terms.

At this point you may be interested to learn that I created the first typewriter with Hebrew characters. I then had Samaritan letters cut to my specification and had the Samaritan letters put onto the typewriter in place of the upper case, so that I could have both alphabets together: with the upper case I write to the Samaritans in their script, while with the help of the lower case I transcribe Samaritan letters and writings.[1]

Figure 2: Moses Gaster’s Samaritan Hebrew typewriter, with a letter from Gaster to the High Priest Jacob son of Aaron, ca. 1910. Typewriter: New York University Libraries, Letter: The John Rylands Research Institute and Library, The University of Manchester, Moses Gaster Collection, courtesy of Benyamim Tsedaka. Photo copyright Museum of the Bible 2022.

Moses Gaster was a profoundly humane scholar of the humanities. Born in Romania to a Jewish family, he was well educated both in his faith and secular studies before obtaining a doctorate in Romanian philology and later rabbinic ordination. He became a well-known expert in Romanian folklore and was a vehement Romanian royalist, supporting the monarchy in the face of a pro-democracy movement.

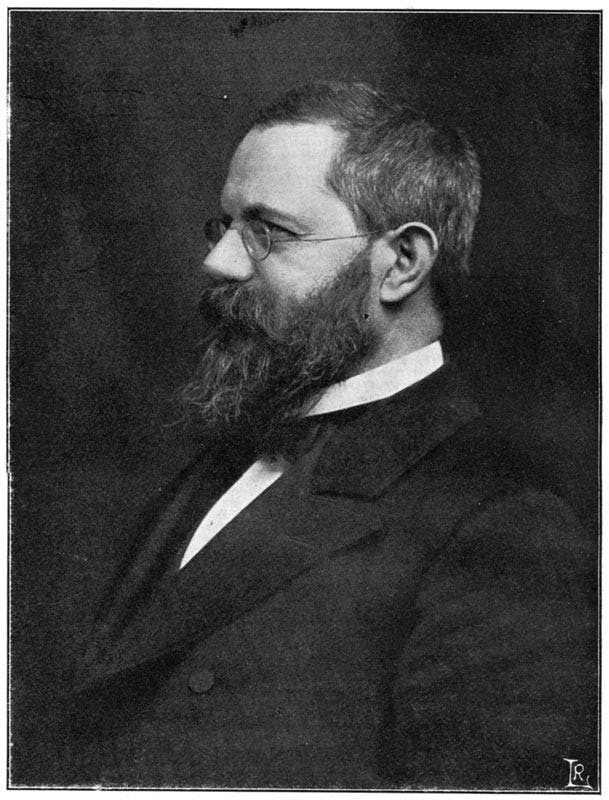

Figure 3: Moses Gaster, from Ost und West, 8–9 (1904): 523–24. Image is in the Public Domain.

It was thus somewhat ironic when he was expelled from Romania in 1885 for his activities on behalf of Zionism, the nascent movement to create a Jewish state in the land of Israel. He quickly re-established himself in London, becoming rabbi of the Sephardic community, teaching at Oxford, and becoming principal of the Lady Judith Montefiore College. It was in England that he began to focus his scholarly career on Judaism, and later the Jews’ Israelite cousins, the Samaritans.

Gaster’s interest in the Samaritans as a scholar went beyond an earlier focus on the text of their Torah, which is different from the Jews’, on their alphabet, and on what ancient Samaritan inscriptions could reveal about the history of the Hebrew language. He was interested in the Samaritans as people. Above all, he wanted to understand how they understood themselves, not just their place in the history of other peoples, especially that of Jews and Christians, writing that he “tried to obtain a sympathetic understanding of the inner life and religious practices of the solitary remnant of the Ancient House of Israel."[2]

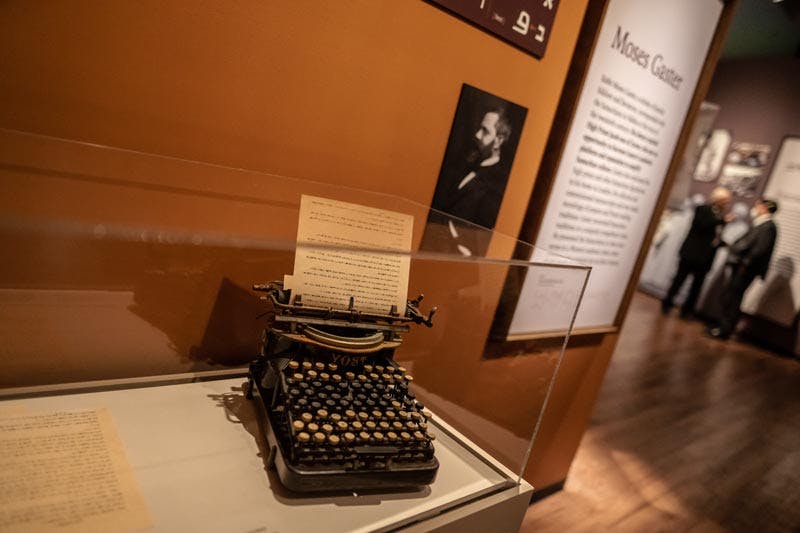

Figure 4: Moses Gaster's typewriter on display in the exhibition. Photo copyright Museum of the Bible 2022.

Museum of the Bible’s new exhibition, curated in partnership with the Yeshiva University Center for Israel Studies, was created in that same spirit. It attempts to present the Samaritans as human beings, in all their complexity, and in their own words. If you have never heard of the Samaritans beyond the good Samaritan and the Samaritan woman at the well mentioned in the New Testament, or if you would like to better understand this ancient people, we invite you to come and experience the Samaritans through their material culture, their stories and beliefs, and their rituals and religious practices. And you can also see Moses Gaster’s Samaritan typewriter, an object that reminds us to meet people as they are.

The Samaritans: A Biblical People is open through December 31, 2022, and is included with general admission. You can learn more here.

By Dr. Jesse Abelman, Curator of Hebraica and Judaica

This article is built on the research done in Katherine E. Keim, “‘Joined at Last’: Moses Gaster and the Samaritans,” in The Samaritans: A Biblical People, ed. Steven Fine (Leiden: Brill, 2022), 159–163.

[1] Moses Gaster, The Samaritans: Their History, Doctrines and Literature (London: The British Academy, 1925), 20.

[2] Gaster, The Samaritans, preface, n.p.