Basilica Sancti Petri—A New Exhibition from the Vatican

Have you ever wondered why church buildings around the world often share a similar architectural plan? The roots of this design date back to the time of Constantine I, the Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337. In AD 313, Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, which decriminalized Christianity and allowed Christians to worship in public. The first buildings used for this purpose were Roman basilicas, which had both civic and public functions. Roman basilicas were gathering places used to conduct business, hold court, and address the needs of the community. Each was designed as a single, long hall divided by rows of columns. Entrances, large windows, and apses could be arranged either on the long or on the short sides.

Under Constantine’s patronage, architects took this design and altered it into what we today recognize as a church. At first, only a few functional adjustments were made. The main difference was to the building’s orientation. A single apse now occupied one of the short sides, while the entrance occupied the other. Thus, upon entering, the visitor was drawn to the apse (which came to hold the altar), which became the focal point of the entire building. As time passed, additional changes were made to the basilica plan, such as extensions on either side of the apse (transept) and the addition of a long courtyard in front (atrium or quadriporticus), transforming it into one of the most recognizable symbols in the world — a cross.

Through a series of prints on loan from the Vatican Library, Museum of the Bible’s latest exhibition presents the most famous example of this transformation, Saint Peter’s Basilica. In addition, this exhibition explores the historical conversion of a secular space into a sacred one, highlighting the importance of architecture in religious tradition.

Figure 1: A view of the title wall of the exhibit.

Saint Peter’s Basilica was originally built by Constantine during the pontificate of Pope Sylvester I (AD 314–335) and is the first Christian church to be built on the burial site of a martyr — the apostle Peter. The building makes literal the verse, “You are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church” (Matthew 16:18).

The original Saint Peter’s Basilica was used for 12 centuries before falling into disrepair. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, it was decided to demolish the basilica and rebuild. The old basilica was slowly torn down to make room for the new Saint Peter’s standing today.

Prints of the original Constantinian structure can be seen in the exhibition alongside plans for the new structure, first put forth by Donato Bramante in 1506. The new building was to be a centrally planned church in the shape of a Greek cross (a cross with four equal arms crossed at the middle) enclosed in a square. Bramante oversaw the project from 1506 until his death in 1514. At that point, much of the old basilica was demolished, and the gigantic pillars and four arches that would support the new central dome were built, as well as portions of the southern arm of the Greek cross.

Figure 2: Design according to Donato Bramante. Engraving by Agostino de'Musi — Antonio Salamanca, 1517.

Building projects as grand as this one took years to complete, which is why cathedrals often sport architectural styles from different centuries. Since it was a church, it needed to remain functional, so there was a period of time when both the old basilica and the new existed together in various states of demolition and completion. Two of the prints on display show this period of transition.

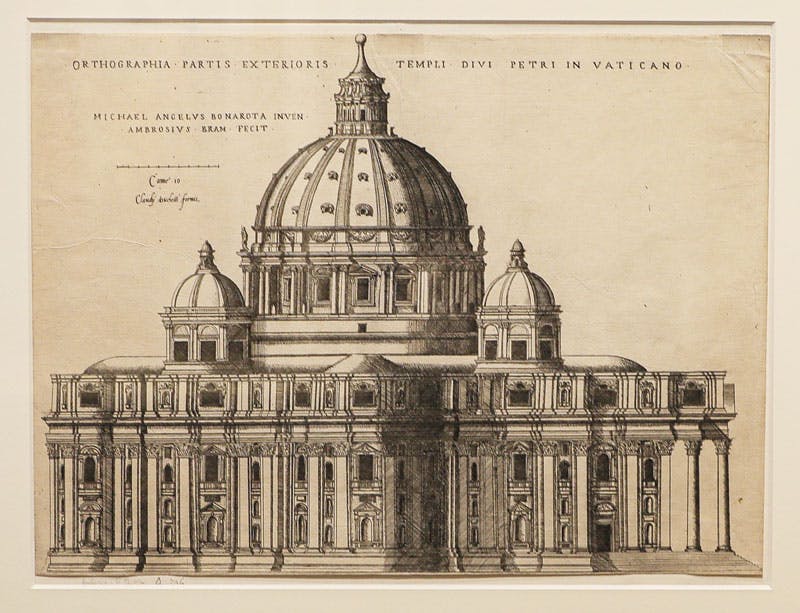

As time passed and styles changed, alterations to the exterior were proposed to make the building grander and more in fashion. The artist Antonio da Sangallo sketched an elaborate, updated façade, but died before the plan was carried out. Michelangelo Buonarroti took up Sangallo’s work, making plans to alter the dome and shorten the bell towers on either side. Eventually, Michelangelo’s façade was built, but Bramante and Michelangelo’s Greek plan church turned out to be too small. So, the main aisle was extended by Carlo Maderno, creating a plan that resembles a more traditional cross rather than the Greek cross.

Figure 3: Design according to Michelangelo Buonarroti. Engraving by Ambrogio Brambilla, ca. 1580.

Further additions to the colonnade in front of the basilica are depicted in the remaining prints on display. Designed by Gianlorenzo Bernini, this circular colonnade was created as a metaphorical embrace of all Christianity.

Christian architecture was a novelty in that it turned a secular building into a sacred one, transforming it into the shape of a cross, a symbol that had also been transformed by Christians from one of rejection and death to one of victory. As one looks down the main aisle, called the via salutis, or “way of salvation,” one looks toward Jesus and his sacrifice. As one looks up into the beautifully decorated dome, one looks toward the heavens and thinks on things above. As one is bathed in light cascading down from rows of clerestory windows, one is surrounded by the light of God.

Come and learn more about Christian architecture in Basilica Sancti Petri: The Transformation of Saint Peter’s Basilica at Museum of the Bible, now through September 25, 2022.

By Amy Van Dyke, Lead Curator of Art and Exhibitions, and Dr. Corinna Ricasoli, Consultant Curator of Fine Arts

To learn more about the exhibition, visit the exhibit landing page.