May I Have Your Autograph?

Martin Luther’s fame as the author of the 95 Theses, the translator of the Bible, the writer of hymns such as "A Mighty Fortress," and the man who defied popes and an emperor is deeply entrenched in popular imagination. Museum of the Bible has many items associated with Luther in its collections. There are even a few with Luther’s autograph.

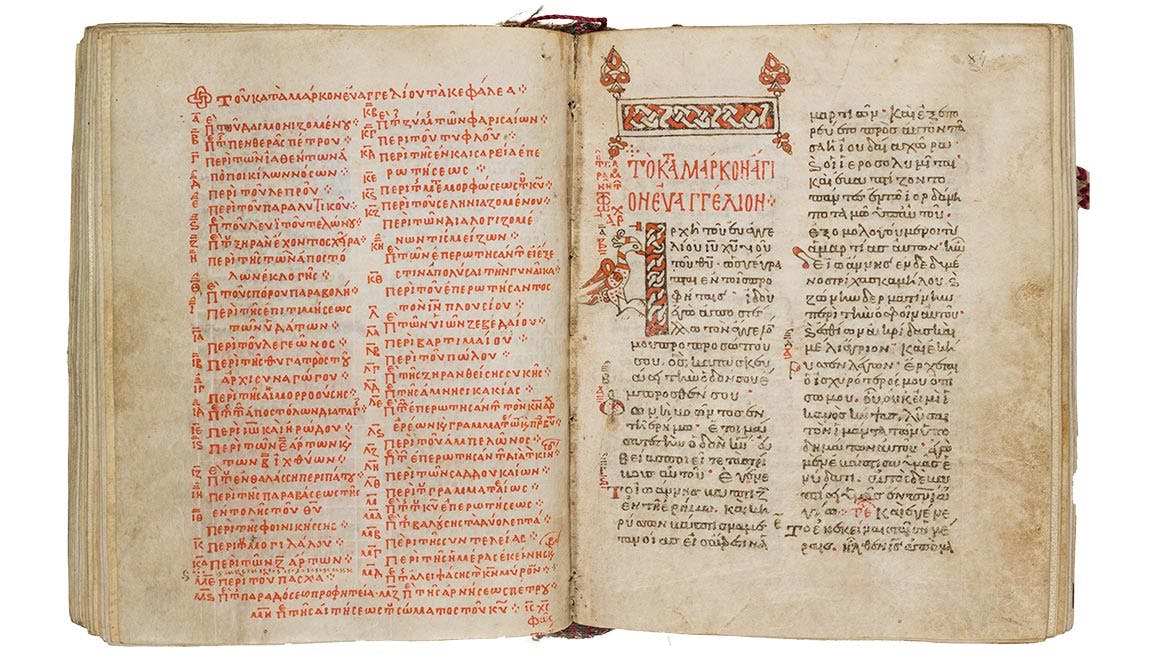

Our collections also contain two small booklets printed in the first quarter of the sixteenth century, each with a lengthy handwritten dedication in brown ink, a date, and the name Martinus Luther. The first of these inscriptions appears in PBK.000186, a 1518 Aldine Press edition of the love poetry and elegies of the Italian humanist Giovanni Gioviano Pontano (1426–1503).

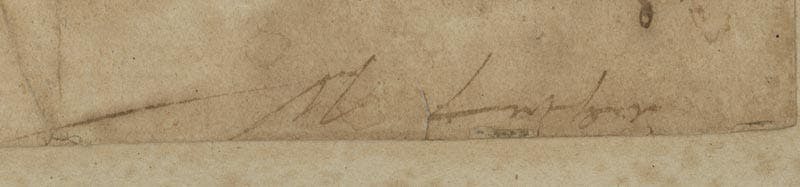

Figure 1: Front pastedown of PBK.000186, showing a forged Luther signature. Click here to see more on the Collections page.

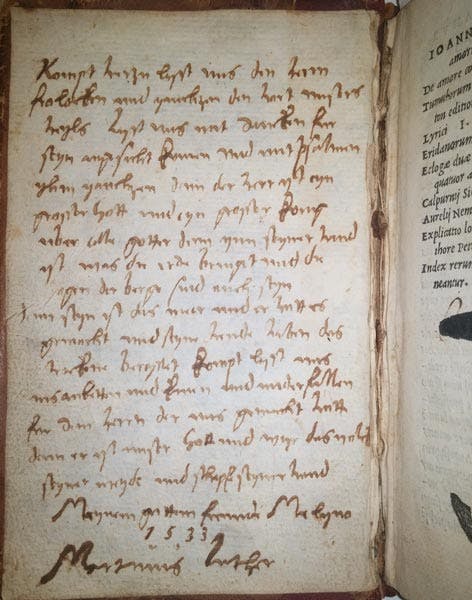

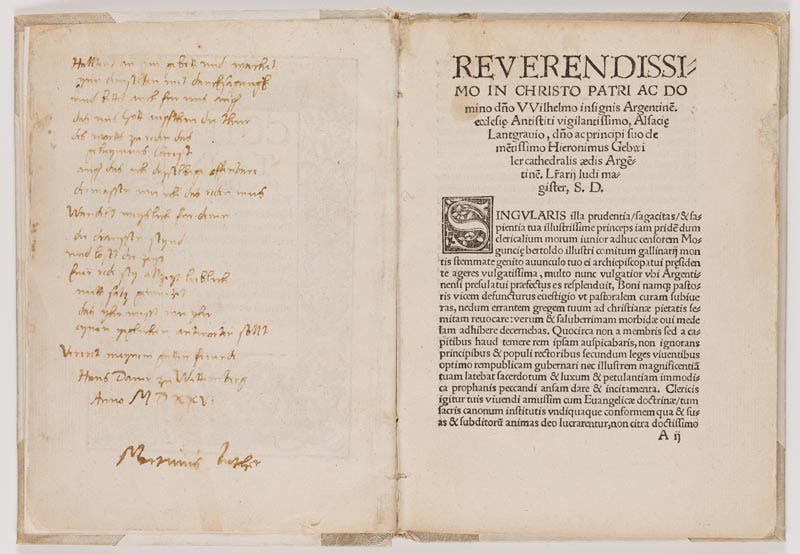

The inscription begins with the first seven verses of the German text of Psalm 95. The last lines say, “To my good friend Malyno, 1533, Martinus Luther.” The second appears in PBK.000190, a 1523 collection of miscellaneous Latin Patristic texts compiled by Hieronymus Gebwiler, the headmaster of the cathedral school in Strasbourg, France.

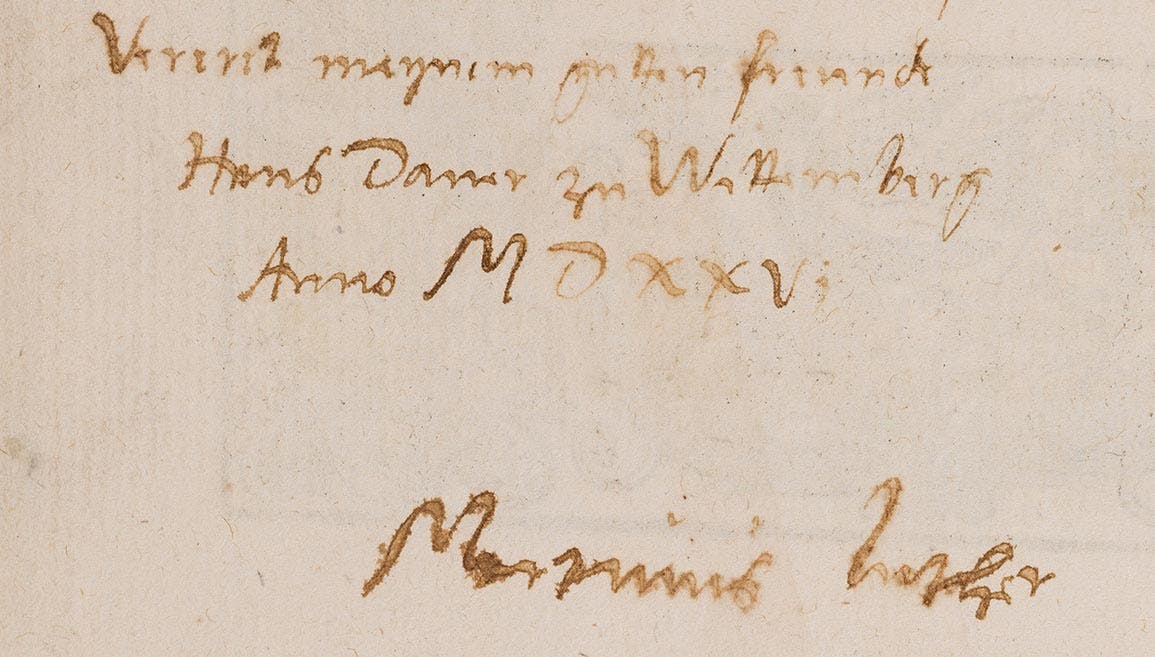

Figure 2: Inscribed page in PBK.000190, showing a forged Luther signatures. Click here to see more on the Collections page.

A 15-line poem begins with an exhortation to hold on to prayer and the truth, then concludes with these additional lines, “Dedicated to my good friend, Hans Dann at Wittemberg (sic), in the year 1526.”

There is something odd about each of these dedications. Why would Luther give a good friend a book containing Pontano’s poetry about conjugal love and his steamy affair as an old widower with a much younger woman? And why would Luther give another good friend a book containing texts specifically selected to contradict his own teachings? The miscellany contains Isidore of Seville’s work on the sects and names of heretics, Augustine on faith and works, and Jerome on the perpetual virginity of Mary and the veneration of relics of the saints. The answer is quite simple. He didn’t.

Both inscriptions are the work of the notorious nineteenth-century forger, Hermann Kyrieleis, who capitalized on the enduring popularity of Luther and his works in Germany. Between 1893 and 1896, Kyrieleis produced at least 130 Luther forgeries. What is most astounding is he had little formal education beyond elementary school. Using nineteenth-century lithographic facsimiles of Luther’s work, Kyrieleis patiently copied the reformer’s handwriting until he mastered it. He then churned out multiple copies of the Lord’s Prayer, “A Mighty Fortress,” and the 23rd Psalm, all written with astounding precision in Latin books printed in the sixteenth century. Next, his wife and young daughter would go to an antiquarian bookdealer in a city such as Berlin, Vienna, or Milan with a convincing tale of financial woes. To make ends meet, the poor family was forced to sell a precious heirloom handed down for generations. She then produced the book to show the bookdealer Luther’s inscription. Kyrieleis’s work was so convincing it fooled most experts.

Eventually, he flooded the market with forgeries, and when multiple copies of certain texts, such as “A Mighty Fortress,” appeared in different cities, scholars became suspicious. In 1896, the German theologian and Luther scholar Georg Buchwald, published the first article about the forgeries, titled, “An Unheard-of Fraud with Luther Autographs.” Buchwald said that “by their content, the inscriptions represent the peak of insolence of the forgeries. To my knowledge, we don’t possess a single hymn of Luther’s in his own handwriting.” The police finally caught up with Kyrieleis and his wife, and they stood trial in Berlin. Kyrieleis’s statements in the courtroom convinced the judge that he was insane, and so the court sent him to an asylum. Kyrieleis’s wife spent 10 months in prison for her role in the conspiracy. Kyrieleis got out of the asylum before his wife got out of prison, and then the two disappeared.

In 1905, Max Herrmann, a scholar of German literature and founder of German theater studies, presented a lecture about the forgeries in Berlin. Herrmann had access to the court records and the confiscated forgeries used as evidence in the trial. He described the paleographical basis for recognizing these autographs as forgeries. Although the signatures were ostensibly dated from 1522 to 1544, they did not exhibit the evolution in handwriting that genuine Luther texts showed over the same period.

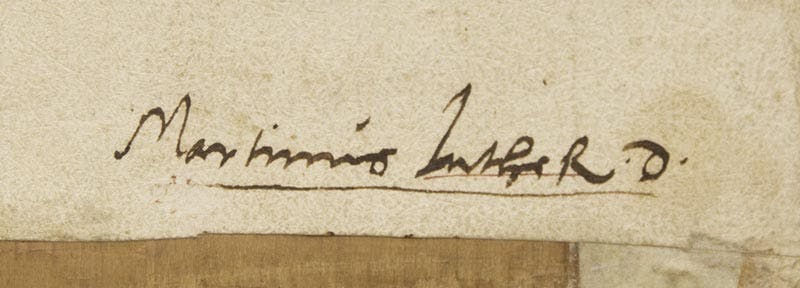

Figure 3: Close up of Martin Luther's signature in 1518.

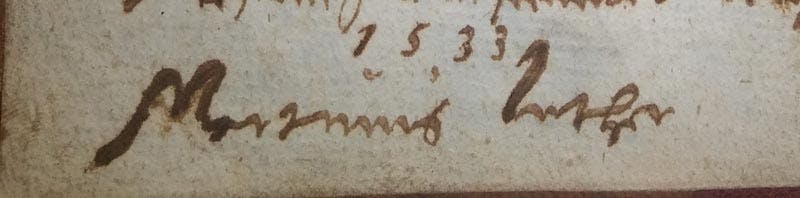

Figure 4: Close up of Martin Luther's signature from 1545, showing the paleographical changes in how he signed his name.

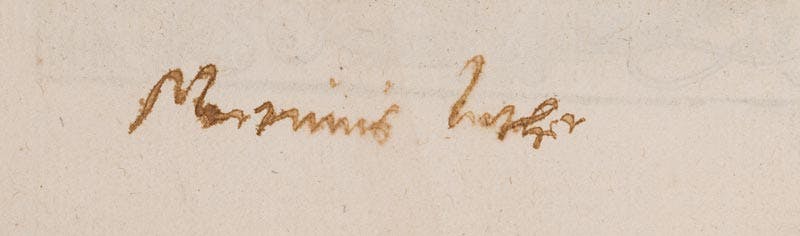

Figure 5: Close up of one of Kyrieleis's forged Martin Luther signature. The differences between the forged and authentic signatures are slight but noticeable when compared directly.

Figure 6: Close up of another of Kyrieleis's forged Martin Luther signatures. The differences between the forged and authentic signatures are slight but noticeable when compared directly.

He also described the forensic studies carried on by Dr. Paul Jeserich in Berlin that showed the forger did not use iron gall ink that was typical in Luther’s time, but a plant-based ink that was easy to make. This ink dripped into tiny wormholes in the paper, showing that it had been added much later than the apparent date of the inscription. When he had his lecture published, Herrmann included a list of the 91 forgeries known at that time; later scholars expanded the list to 130. PBK.000186 is number 75 and PBK.000190 is number 64 on Herrmann’s list.

The transcript of the trial with some supporting evidence—forged copies of “A Mighty Fortress” confiscated from Kyrieleis’s apartment—perished in the bombing of Dresden during World War II. The fate of Kyrieleis and his wife is unknown, but Max Herrmann lamented the fact that Kyrieleis could have been a great philologist with proper training. Herrmann continued to work in academia until the Nazis forced him to retire in 1933. He died in 1942 in the concentration camp at Theresienstadt (Terezin).

Authentic Luther Artifacts in the Collections

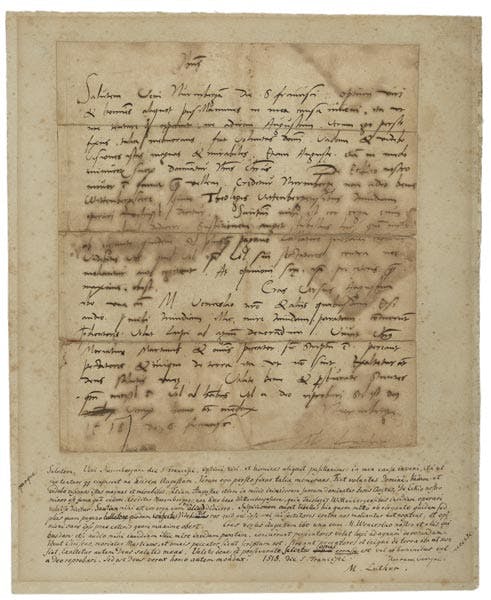

Figure 7: Letter from Martin Luther to his supporters written from Nuremberg, October 4, 1518. Click here to see more on the Collections page.

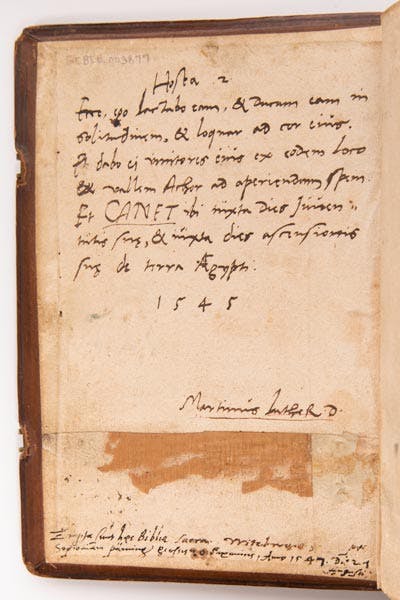

Figure 8: A 1542 Latin Bible signed by Martin Luther in 1545. Click here to see more on the Collections page.