In Their Ancestors' Place: The Prague Haggadah in the Museum Collections

At some point toward the end of the nineteenth century, Edward J. Lewith and his family immigrated to the United States and settled in Charleston, South Carolina, where he prospered, becoming a pillar of the city’s large Jewish community. Rabbi Bernard A. Elzas, in his The Jews of South Carolina, from Earliest Days to the Present published in 1905, lists him as one of “the leading Jewish merchants and citizens of Charleston today.” Unfortunately, Edward died that same year. The date of his death was recorded in a book that was precious to their family, their copy of the 1526 Prague Haggadah.

The Haggadah is the central text of the Seder, the ritual meal celebrated on the first night of the Jewish holiday of Passover, and in the diaspora on the second night as well. At this meal, Jews fulfill the biblical commandment “You shall tell [these words] to your children on that day . . .” (Exodus 13:8) by recounting the story of the exodus from Egypt. It is from the Hebrew words for “you shall tell” — “Ve-Higgadeta” — that the liturgical book read at the Seder gets its name: the Haggadah.

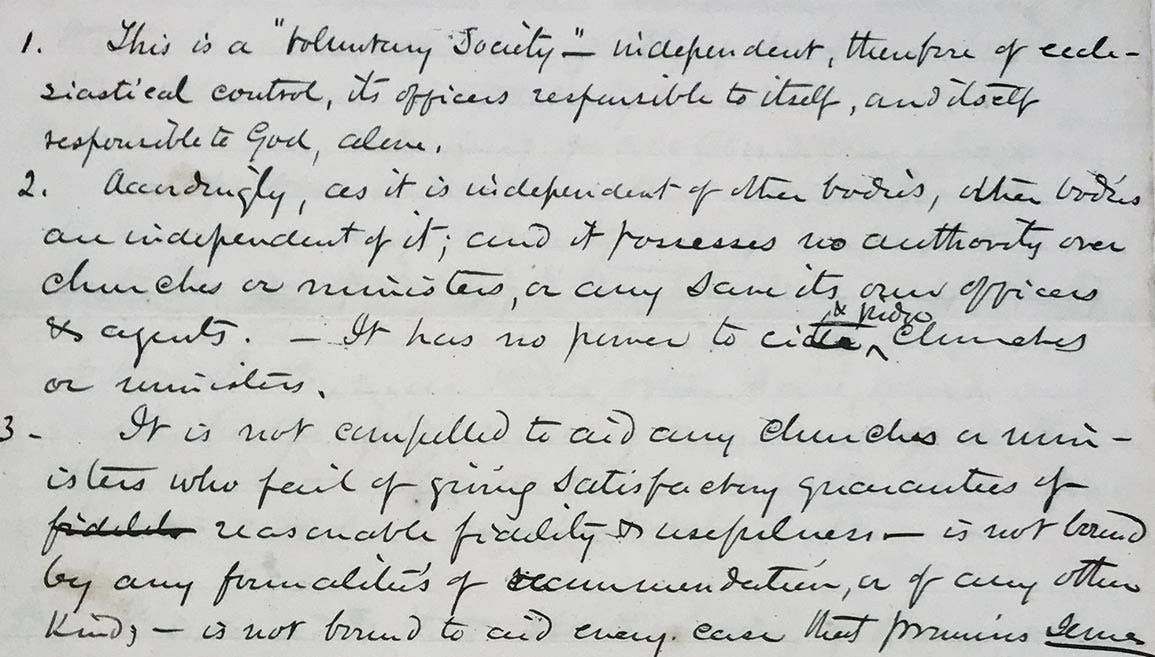

Figure 1: The opening pages of the Prague Haggadah in the Museum Collections. The first word, in large letters just to the left of the image of a man, is 'or, "light.” The text describes the ritual search for leaven on the night preceding the first night of Passover, which is conducted by candlelight, as shown.

With more than 4,000 editions in various languages, it is one of the most printed classical Jewish texts of all time. It combines a retelling of the story of the exodus with songs of praise to God and other observances. The text as it currently exists originated around the tenth century, but at its core is the transformation of a much older biblical ritual: the required gift of the first fruits described in Deuteronomy 26:1–11. The Torah commands the Israelites to bring the first fruit of every tree to the temple as a gift, where they recite a brief summary of the story of the exodus. It is this summary which the authors of the Haggadah used as the basis for retelling the exodus story at the Passover Seder.

Many Haggadot (the plural of Haggadah) include images to illustrate the story of the exodus and to help relate it to contemporary times for the edition’s audience. The Prague Haggadah of 1526 is the earliest fully illustrated printed Haggadah, and its woodcuts had an enormous influence on the history of Haggadah illustration. Printed by Gershom Cohen, the profoundly innovative Hebrew printer, the illustrations are novel and beautiful. The work is exceptionally rare today as only nine copies have survived.

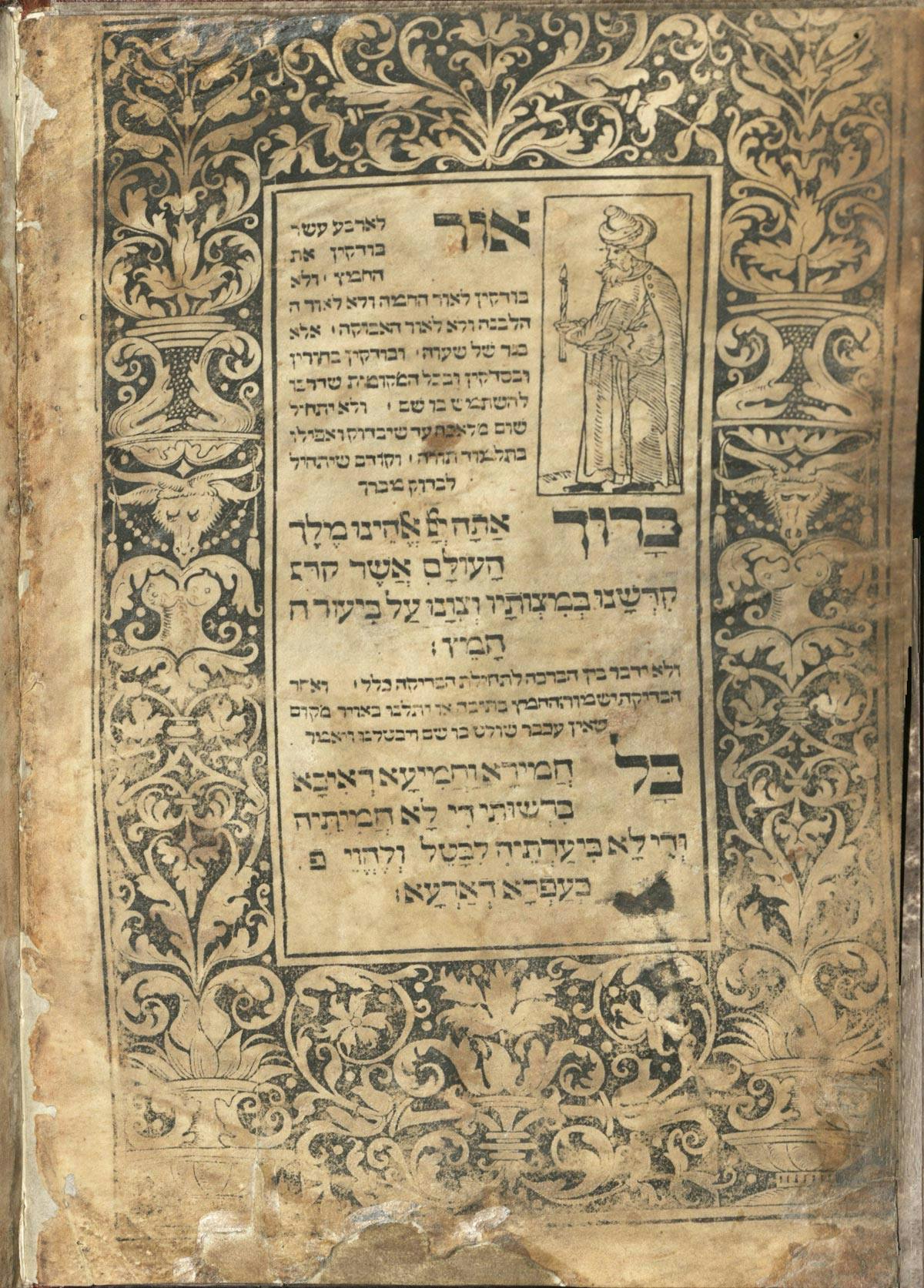

To bring the exodus to life, it depicts the cities the Israelites were forced to build while enslaved to the Egyptians, but it imagines them in sixteenth-century central European architecture so readers could put themselves in their ancestors’ place.

Figure 2: Detail of the two cities. The inscription above the top photo identifies it as (the city of) Pithom. The second inscription identifies the lower image as (the city of) Rameses. These are cities built by the Israelites as Pharaoh’s slaves in the first chapter of Exodus.

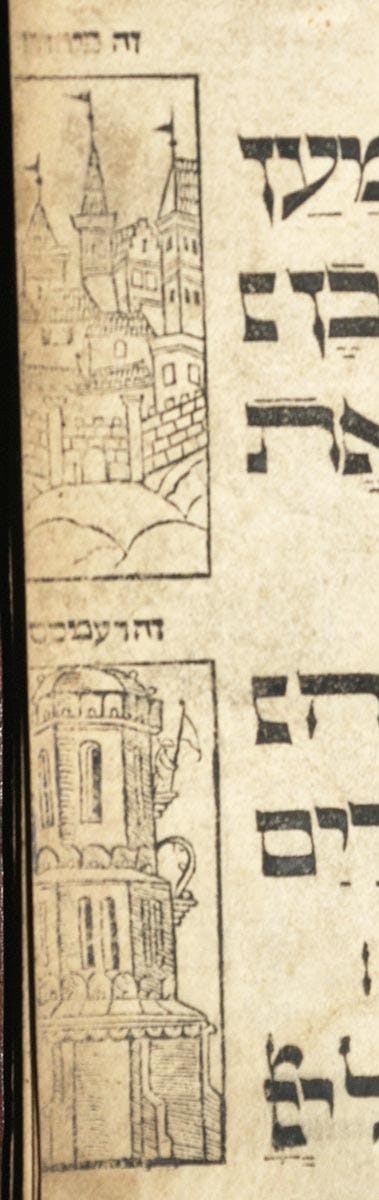

Other aspects of the illustrations place the Haggadah in sixteenth-century Bohemia. For example, the depiction of the four sons, representing four types of children to whom parents might address their telling of the exodus, shows the wicked son as a Bohemian soldier of the period. As the Haggadah says, “In each and every generation a person is obligated to see themself as if they had left Egypt.”

Figure 3: Detail of the "Wicked Son." Though effaced, you can still make out his sixteenth-century attire: short pants, puffy sleeves, wide-brimmed feathered hat.

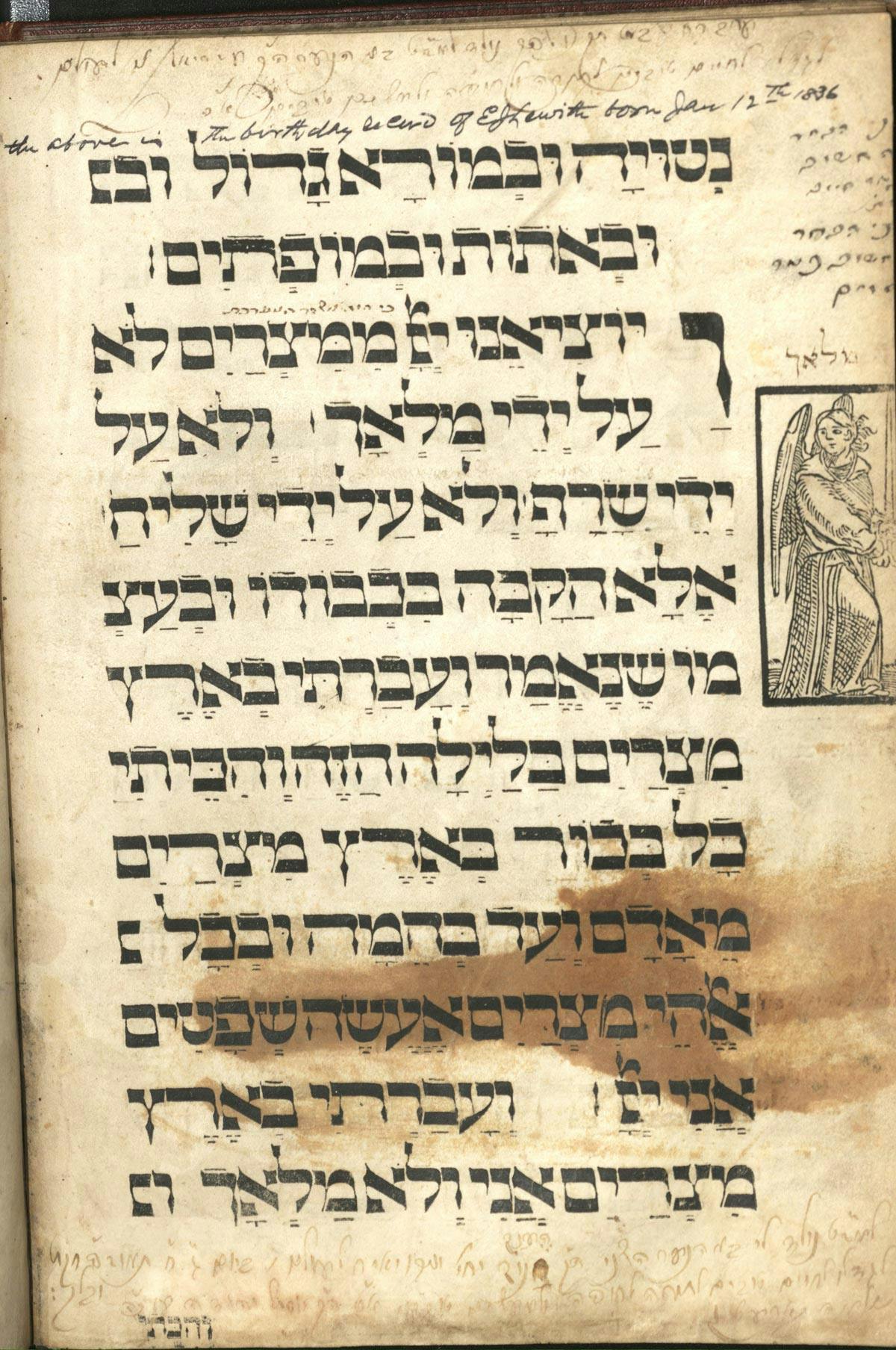

The Lewiths of Charleston, South Carolina, literally put themselves into their Haggadah by recording major family milestones in its pages, much in the way American Christian families record major milestones in family Bibles. Edward’s death is recorded in the margins of their copy of the Haggadah, as well as the births of his children and grandchildren. The dates are recorded in three languages, Hebrew, Yiddish, and English, though not every entry is in every language. In addition to the personal notes written by the family, there are additional notes, written by an unknown author, that discuss the rituals of the Seder.

Figure 4: At the top of the page in Hebrew with an English note is the record for Edward Lewith's birthday on January 12, 1836.

The Lewith family continued to be prominent in Charleston through the twentieth century. They were members of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, one of the oldest synagogues in the United States, founded in 1749. It also has a plausible claim to be the first Reform synagogue in the US, adopting a new charter in 1824 based on ideas being expressed by the liberalizing movement in Europe, and which would become the largest American Jewish denomination for most of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. In 1947, Edward Lewith’s daughter, Josephine Frances Schafer, donated this copy of the Prague Haggadah to the synagogue, where it was kept until 1982, when it was necessary to sell because of financial need.

The Passover Seder is one of the most commonly observed rituals in American Jewish life. Aside from its uplifting narrative of liberation, it represents a connection to tradition and family. In many ways, that may be what the Lewiths’ copy of the Prague Haggadah represented to them, with its recording of their major milestones and evidence of the growth of their family. Reading their Haggadah at every Seder, they recounted the story of the exodus while also encountering the history of their family, connecting their story to the story of national liberation, a story that resonated deeply in their American home.

The Prague Haggadah is on display at the museum in the Bible in America exhibit on our Impact Floor. Or you can check it out online on the Museum Collections page.