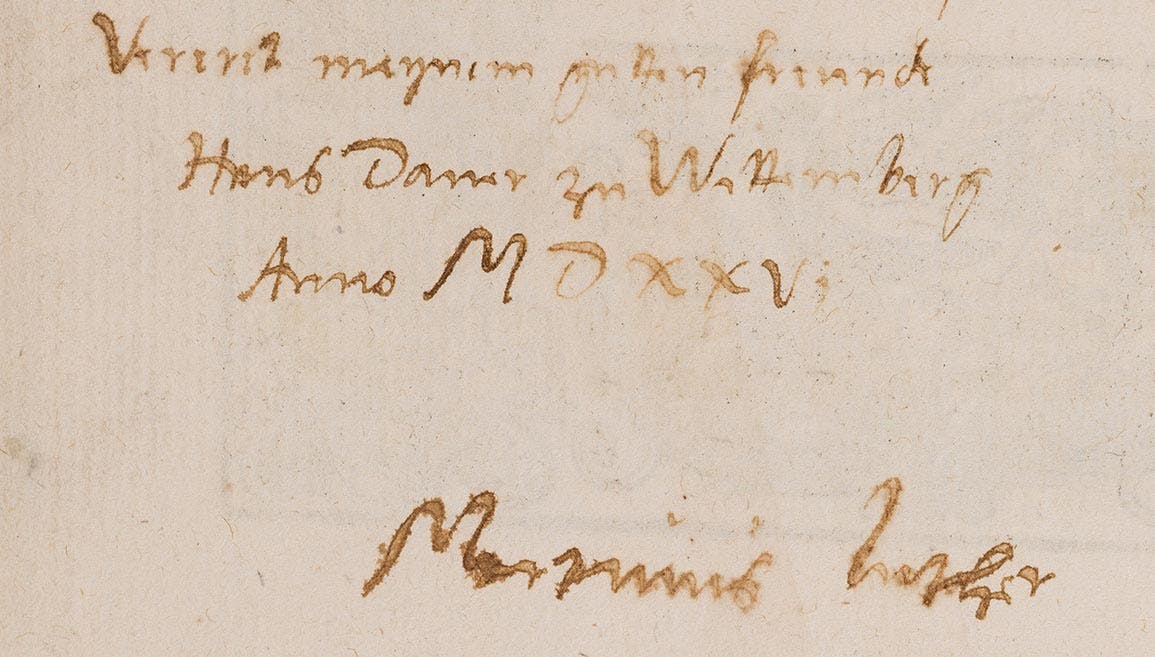

“From Imperfect Men”: A Glimpse into the American Debate over Slavery

Black History Month at Museum of the Bible has been filled with rich stories about the ways Black Americans have engaged with the Bible. These stories have spanned centuries and involved both persecution and perseverance, suffering and joy, oppression, and victory. In all of them, the Bible shined as a beacon of hope. Yet, the struggles were often intense, especially in the period leading up to the Civil War. In the national debate over slavery, church bodies were divided over how to handle the issue and both sides appealed to the Bible for their positions. A manuscript in the Museum of the Bible’s Steinbock Collection written around 1857 helps illustrate this conflict. It is a working document likely composed by a leader of the American Home Missionary Society (AHMS) as the organization moved to sever ties with ministers and churches who sought to “perpetuate & extend the system of slavery.” By reading it, one can sense the tension, suspicion, and confusion these religious leaders felt in a debate that would help shape the course of Black history and the nation as a whole.

The American Home Missionary Society was formed in 1826, one of many voluntary religious organizations that arose in the early part of the nineteenth century to promote a particular cause. Other organizations included the American Bible Society (1816), the American Tract Society (1825), and the American Temperance Society (1826). The AHMS was composed primarily of members of the Presbyterian, Congregational, and Reformed Churches. Based in New York City, it was the outgrowth of a merger between numerous smaller missionary organizations. Its cause was to provide financial support for fledgling churches and to coordinate missionary activity across the United States as the young country’s borders expanded across the North American continent.

The AHMS grew rapidly due to the contributions of churches and individual donors from every corner of the country. In the years before the Civil War, the society supported around 1,000 missionaries annually, most of whom worked within states and territories along the Great Lakes and west of the Mississippi River. In its first three decades, it received nearly one million dollars in revenue, which it used to support tens of thousands of churches, Sunday schools, and Bible classes. In its annual report from 1857, the society’s Executive Committee framed the organization’s success in another way. If you added all the months that all its missionaries had worked since 1826, the combined total would equal around 18,076 years of missionary activity.

The AHMS had assumed a neutral, or “noninterference,” stance on the great question of slavery, even though its center of gravity was in the North and some of its most generous supporters were abolitionists. By the 1850s, however, the Executive Committee noted how the rhetoric had grown more intense. Black and white abolitionists had become more vocal. Southern ministers who were neutral or who opposed slavery were forced to leave their positions. What does the Bible say about slavery? How could slavery coexist with the biblical command to love one’s neighbor? Should the society support slaveholding ministers? Should it assist churches with slaveholding members? Today, the answers to such questions might seem obvious, but at that time many Americans were divided on how to read the Bible and apply its teachings. Some churches formally split into Northern and Southern factions, such as the Methodist and Baptist Churches in 1844 and 1845, respectively. While others might not have formally divided, every faith community felt the effects of the debate. Both sides used the Bible to justify their claims and condemn their opponents, which only worsened the sectionalism that led to war.

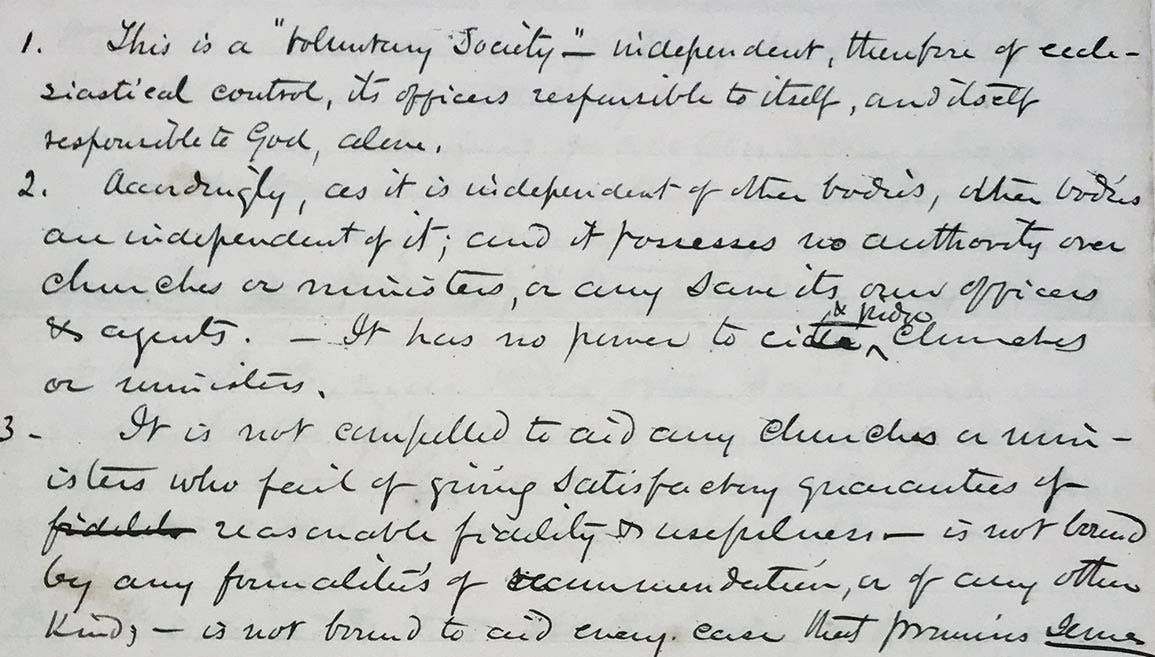

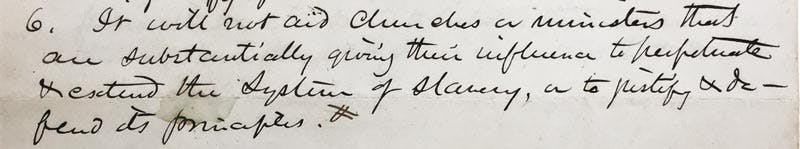

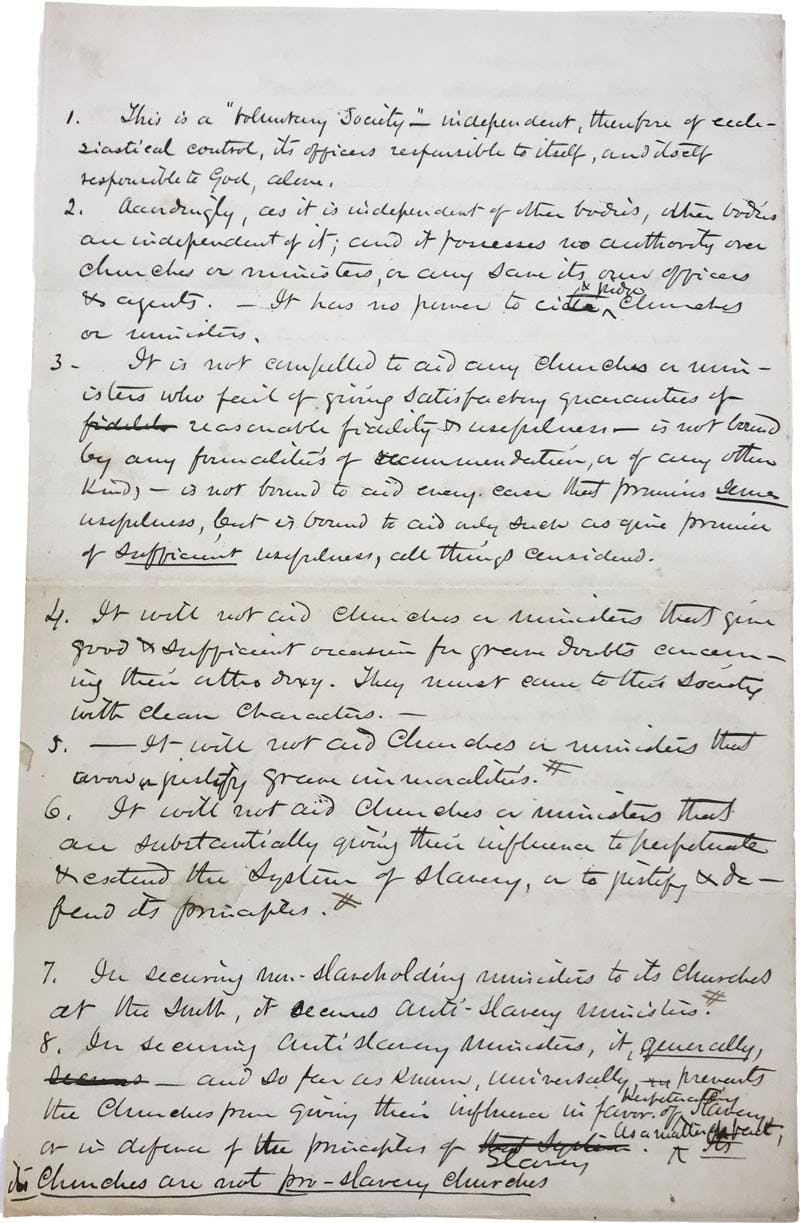

In 1857, facing increasing pressure from donors, the AHMS’s Executive Committee finally adopted a resolution that largely severed connections to slaveholding churches and ministers. The manuscript here was likely created amid this internal debate. It sketches out the society’s position in twelve articles. The first half outlines the society’s purpose and limited authority in denominational affairs. The second half turns to the issue of slavery, with Article 6 stating the society “will not aid churches or ministers that are substantially giving their influence to perpetuate and extend the system of slavery, or to justify and defend its principles.”

Figure 1: Detail of Article 6. See below for images of the full document and a transcription.

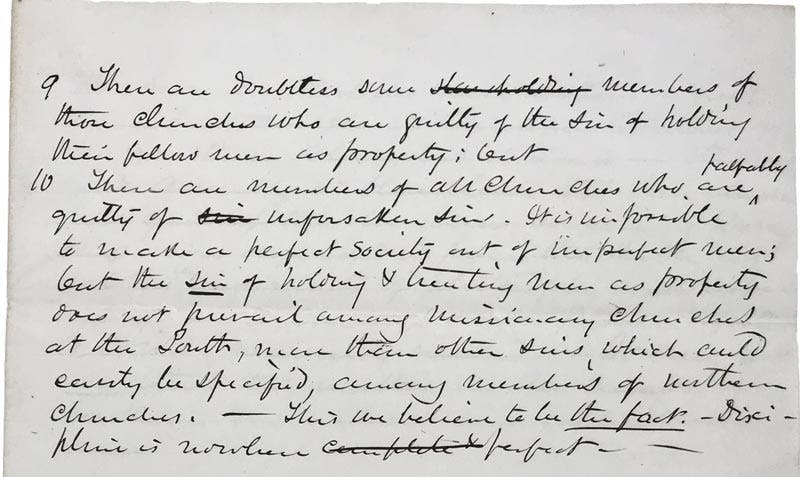

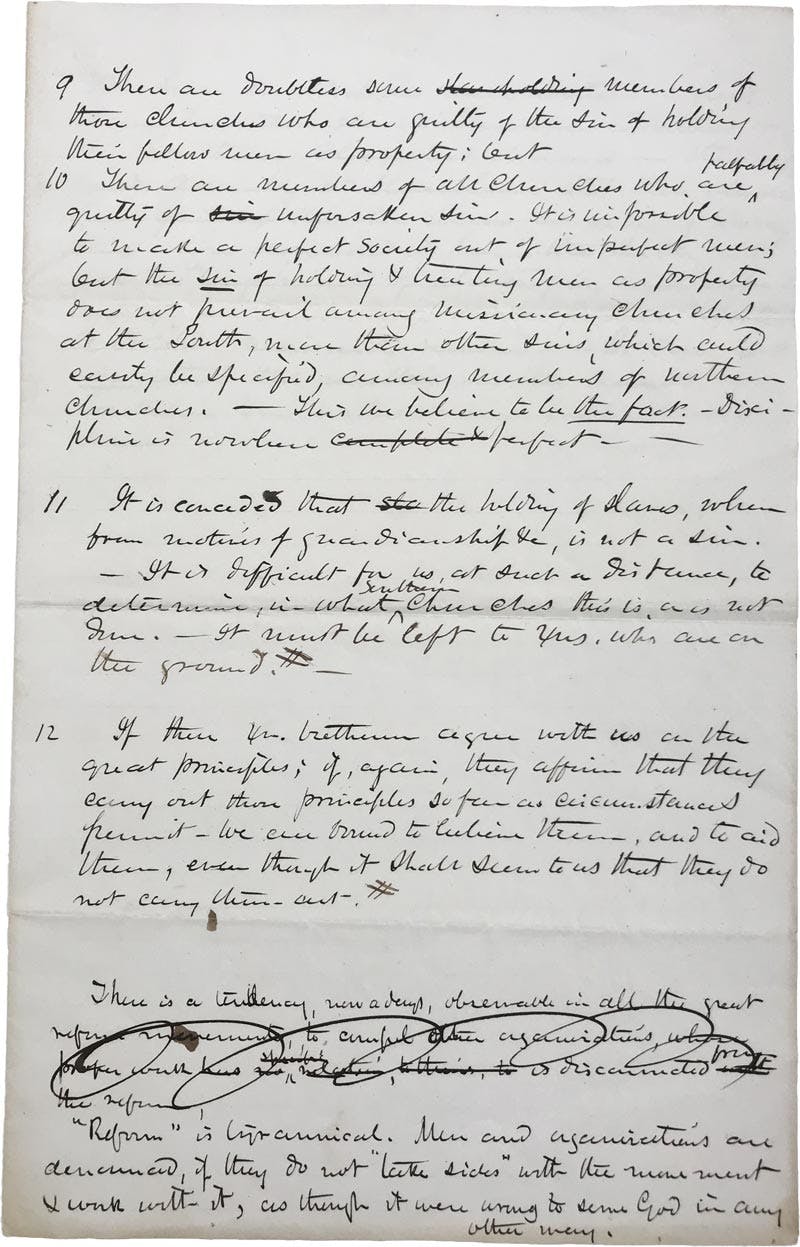

Throughout the document are several corrections and adjustments to language that indicate at least some of the more contentious details of the subsequent articles. Articles 9 and 10, for example, focus on the sin of enslaving people. Why single out this sin when all churches are full of sinners? Some of their ambivalence is captured by two statements, “It is impossible to make a perfect society out of imperfect men” and that “Discipline is nowhere perfect.” According to the author, there are also certain circumstances where “the holding of slaves” might be tolerated for the time being, such as for those who inherited enslaved people and were now bound to keep them through manumission regulations.

Figure 2: Detail of Articles 9 and 10. See below for images of the full document and a transcription.

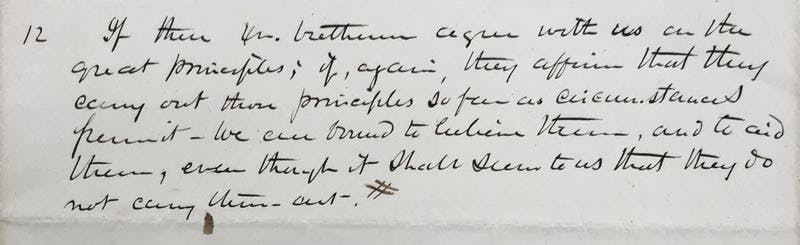

Nevertheless, Article 11 notes that it is “difficult” for the Executive Committee “at such a distance, to determine in what … churches this is, or is not done.” And Article 12 ends with a tinge of despair. It notes that the AHMS is bound to believe the affirmations of those “Christian brethren [who] agree with us on the great principles,” but ends with, “even though it shall seem to us that they do not carry them out.”

Figure 3: Detail of Article 12. See below for images of the full document and a transcription.

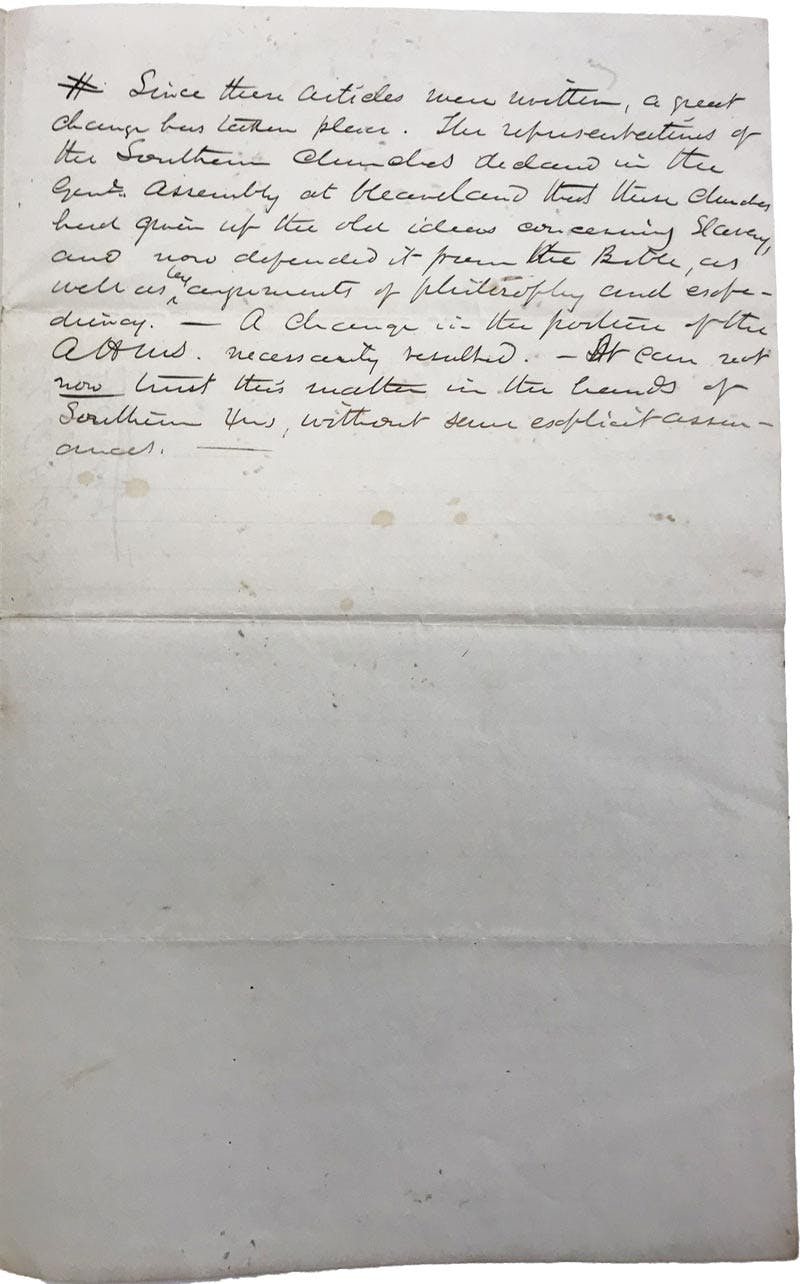

The writer’s fear at the end of Article 12 seems to have become a reality. The document concludes with an addendum that helps illustrate the climate of division and distrust, stating that there had since been changes to certain articles because the Executive Committee “can not now trust this matter in the hands of Southern Christians, without some explicit assurances.” The tense emotions of wrestling with “the great principles,” many of which were connected to the Bible, can be seen in the writing itself. Words are crossed out or scrawled above carets, corrections are hastily made, several dashes set off terse comments and glosses, and a set of hashtags seems to mark the articles dealing directly with antislavery propositions; a final hashtag connects them to the addendum. In this working document, one gains a sense of the climate of antebellum America in the AHMS and the atmosphere that engulfed black and white Americans in the struggle against slavery.

After the Civil War, the AHMS’s success would continue, eventually sponsoring over 2,000 missionaries annually, some of whom worked among newly freed African Americans. Its story is just one example of the much broader debate over the Bible and slavery, which would leave a profound impact on the American religious landscape and the African American experience. You can see more artifacts like this, each telling a story about the abolition movement and the biblical debate over slavery, in the museum’s Bible in America exhibit. Check out future issues of Museum of the Bible Magazine, where we will be showcasing other manuscripts in the Museum Collections related to these and other subjects.

“The AHMS and Slavery”

Figure 4: Page 1 of "The AHMS and Slavery." Note how the author has underlined or crossed out words, and used dashes to explain certain ideas, all pointing to the working nature of the document and the writer's efforts to find the right language.

Figure 5: Page 2 of "The AHMS and Slavery." At the bottom is a note that resists full transcription. Nevertheless, it expresses the frustrations of the writer.

Figure 6: Page 3 of "The AHMS and Slavery." The addendum is marked with a hashtag, which may correspond to the system of hashtags in the first two pages. Research into this document is ongoing.

Transcription of “The AHMS and Slavery”

1. This is a “voluntary society” — independent, therefore, of ecclesiastical control, its officers responsible to itself, and itself responsible to God, alone.

2. Accordingly, as it is independent of other bodies, other bodies are independent of it; and it possesses no authority over churches or ministers, or any save its own officers & agents. — It has no power to order [insert: or pi…] churches or ministers.

3. It is not compelled to aid any churches or ministers who fail of giving satisfactory guarantees of [crossed out: fidelity] reasonable fidelity — & usefulness — is not bound by any formalities of accommodation, or of any other kind, — is not bound to aid every case that promises their usefulness, but is bound to aid only such as give promise of [underlined: sufficient] usefulness, all things considered.

4. It will not aid churches or ministers that give good & sufficient occasion for grave doubts concerning their orthodoxy. They must come to this society with clean characters. —

5. — It will not aid churches or ministers that cover or justify grave immoralities.#

6. It will not aid churches or ministers that are substantially giving their influence to perpetuate & extend the system of slavery, or to justify & defend its principles.#

7. In securing no slaveholding ministers to its churches at the South, it secures anti-slavery ministers.#

8. In securing antislavery ministers, it, [underlined: generally], [crossed out: secures] — and so far as known, universally — prevents the churches from giving their influence in favor of [insert: perpetuating] slavery, or in defense of the principles of [crossed out: that system] slavery. As a matter of fact, [insert and underlined: its [sic] its churches are not pro-slavery churches]

9. There are doubtless some [crossed out: slaveholding] members of those churches who are guilty of the sin of holding their fellow men as property; but

10. There are members of all churches who are [insert: palpably] guilty of [crossed out: sin] unforsaken sin. It is impossible to make a perfect society out of imperfect men; but the [underlined: sin] of holding & treating men as property does not prevail among missionary churches at the South, more than other sins, which could easily be specified, among members of northern churches. — This we believe to be [underlined: the fact.] — Discipline is nowhere [crossed out: complete &] perfect. —

11. It is conceded that [crossed out: sla] the holding of slaves, when from motives of guardianship etc., is not a sin. — It is difficult for us, at such a distance, to determine in what [insert: Southern] churches this is, or is not done. — It must be left to Xns. (= Christians) who are on the ground.# —

12. If these Xn. (= Christian) brethren agree with us on the great principles; if, again, they affirm that they carry out those principles so far as circumstances permit — we are bound to believe them, and to aid them, even though it shall seem to us that they do not carry them out.#

[The following paragraph was scribbled out] There is a tendency, now a days, observable in all this great reform movements, to compel other organizations, whose proper work [crossed out: has no] [insert and crossed out: specific] [crossed out: relation to theirs, to] is disconnected from the reforms.

“Reform” is tyrannical. Men and associations are denounced, if they do not “take sides” with the movement & work with it, as though it were wrong to serve God in any other way.

# Since these articles were written, a great change has taken place. The representatives of the Southern churches declared in the Genl. Assembly at Cleaveland [sic] that these churches had given up the old ideas concerning slavery, and now defended it from the Bible, as well as [insert: by] arguments of philosophy and expediency — A change in the portion of the articles necessarily resulted. — It [underlined: can not] now trust this matter in the hands of Southern Xns. (= Christians), without some explicit assurances. —

By Dr. Anthony Schmidt, Director of Collections & Curation