The Early Years (1725–1735)

With great passion often comes great struggle, and it is for this very reason that Newton’s story resonates with people hundreds of years after his passing. In his autobiography, Newton attributes most of his struggles to his own debauchery and poor choices. Plainly, he believed himself to have been a failure on almost every front. His conversion from a creature sinking into despair to a soul redeemed is recorded everywhere in his voluminous writings, but nowhere more plainly or beautifully than in the words of the hymn, “Amazing Grace.”

While his father was away at sea, young John was cared for by his mother, Elizabeth. She kept him close at home, teaching him biblical principles and religious hymns. But by age eleven, Newton’s mother had died, and he was sent to his father aboard a ship. In the raucous environment among sailors, Newton wavered between his established moral principles and this new lifestyle. He soon set aside ideas from his childhood and embraced life at sea.

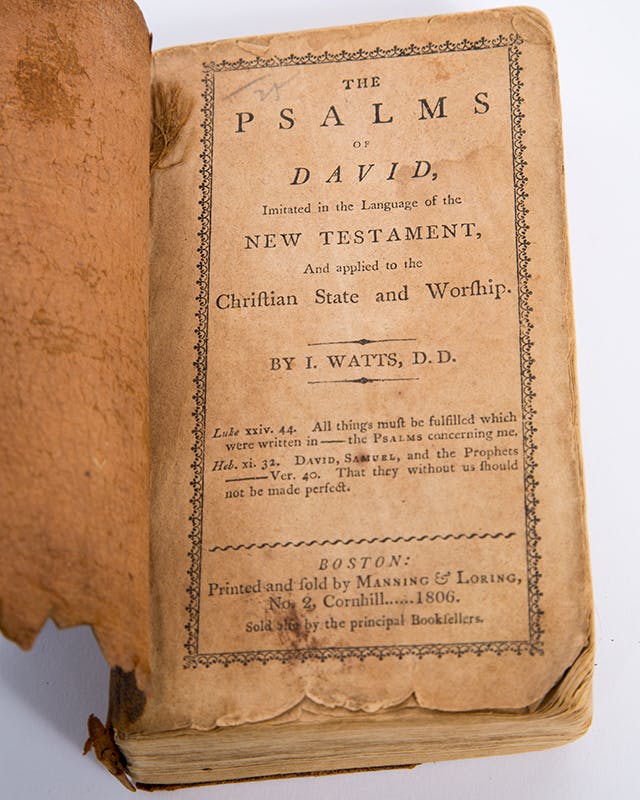

Isaac Watts, The Psalms of David

Printed by Manning and Loring

Boston, MA (US)

1806

PBK.001423

The poems and songs of non-conformist minister and hymn writer Isaac Watts would later influence Newton’s own style of hymn writing.

The Sea Years (1736–1754)

As a young man, Newton was forced into naval service aboard the HMS Harwich, where his poor behavior got him into trouble. To be rid of him, the captain sent Newton to a slave ship bound for Guinea, where his actions led to the eventual punishment of being chained on deck as a captive, with very little provisions.

In 1748, Newton’s father came to his rescue and ordered him to return to England on the Greyhound, but midway through the journey a great storm arose. For days, the crew struggled to keep the ship together, and Newton struggled with himself, reflecting on his poor choices. When the ship, or what was left of it, finally landed in Ireland, Newton made his way to the nearest church and dedicated himself to God.

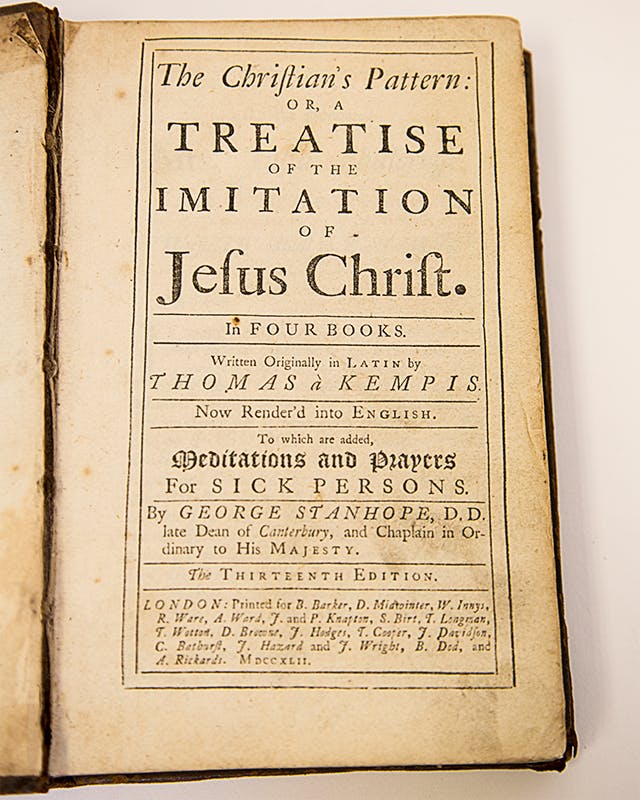

Thomas à Kempis, The Christian's Pattern: Or, a Treatise of the Imitation of Jesus Christ

Edited by George Stanhope

Published by J. Roberts

London (England)

1742

PBK.007446

This edition of The Christian’s Pattern is likely the same as the one Newton would have read while sailing home aboard the Greyhound. Newton describes this book as the one that truly began to “sow the seed of his conversion.”

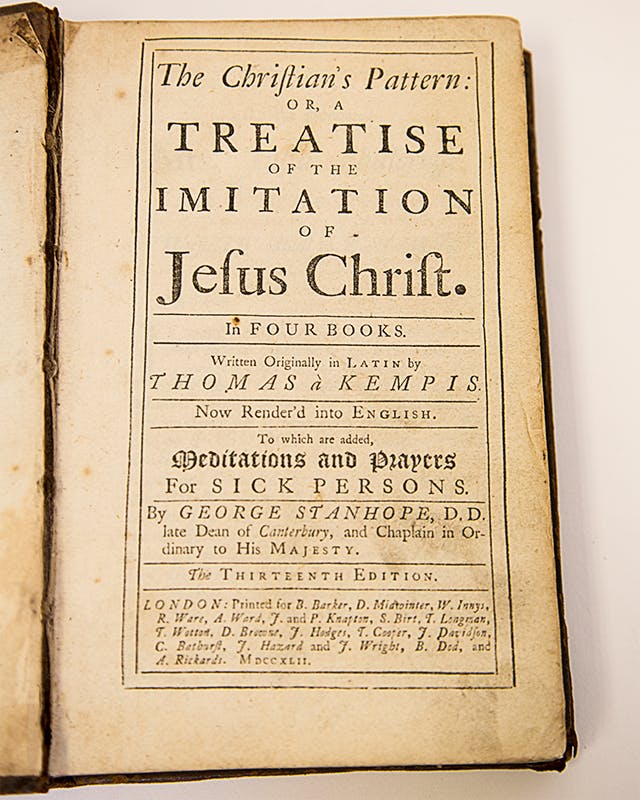

The Slave Trade

Having returned to England, Newton took a job as first mate on the slave ship Brownlow, bound for Charleston, South Carolina. The atrocities of the slave trade had not yet convinced British officials and merchants to stop the business, and Newton, even with his newfound Christian faith, was entangled in the industry. He would later admit he struggled with his occupation and despised it. He believed all people should be treated humanely, having witnessed terrible acts committed against the Africans aboard previous vessels.

He was granted a welcome change in 1754 when a seizure forced his resignation as captain of the African. For Newton, he believed this to be a release from a life in which he felt trapped.

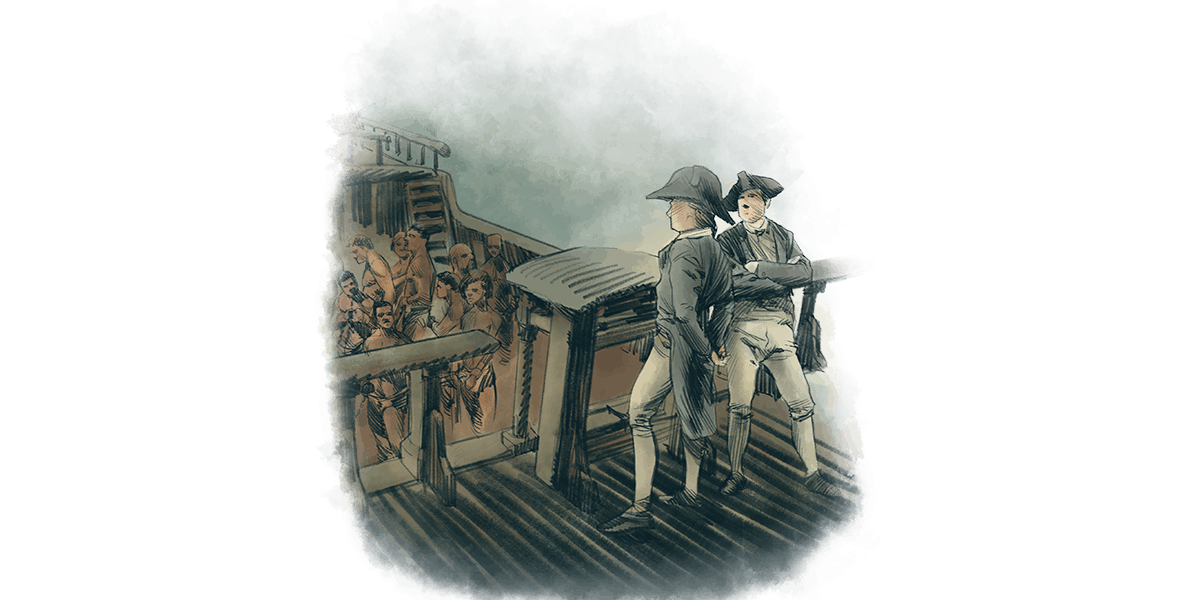

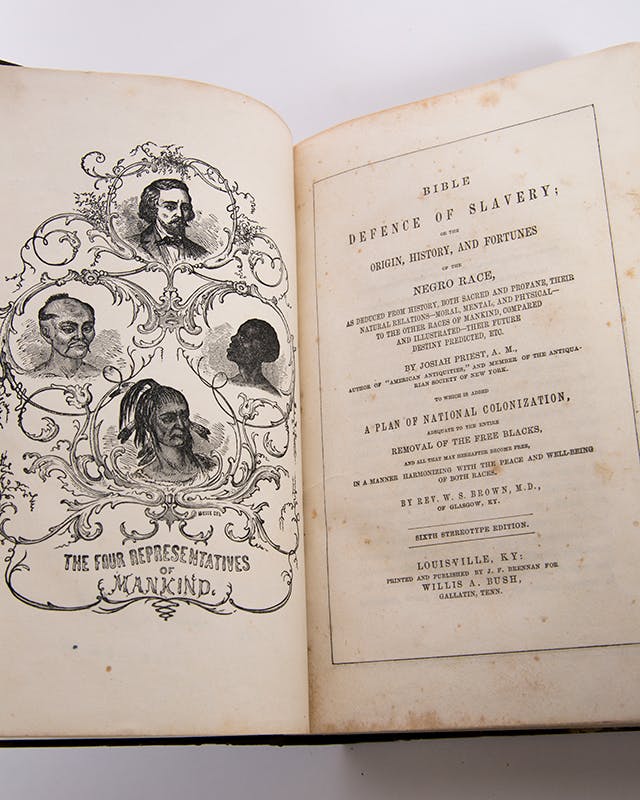

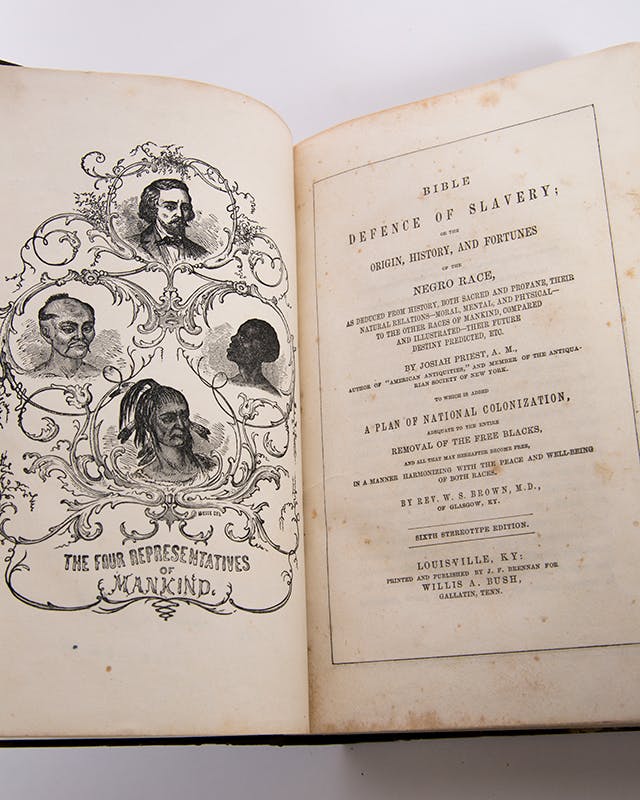

Josiah Priest, A. M., Bible Defence of Slavery

Published by J. F. Brennan

Louisville, KY (US)

1851

PBK.001470

This work sought to justify the removal and enslavement of the African people through arguments from Christian morality and biblical teachings. Those in support of this view believed themselves to be intellectually superior and thus responsible for the well-being of the rest of the world. Colonization, often by force, was unfortunately the result. Therefore, this work was often combined with A Plan of National Colonization.

The Church Years (1755–1807)

After a time, Newton decided to use his interest in Christian writing and teaching to pursue a ministerial position with the Church of England, but without any formal education, he was denied. Over the years, he shared the account of his dramatic past, which caught the attention of John Fawcett and Thomas Haweis. They convinced Newton to finally write his story in a series of letters in 1764, eventually published together as An Authentic Narrative of Some Remarkable Particulars in the Life of Reverend John Newton. Impressed by Newton’s story, Lord Dartmouth recommended him for an appointment within the church, eventually leading to a position at a parish in Olney, England. For the next 43 years, Newton ministered to the parishes at Olney and St. Mary Woolnoth in London, authoring many ecclesiastical books, sermons, letters, and hymns.

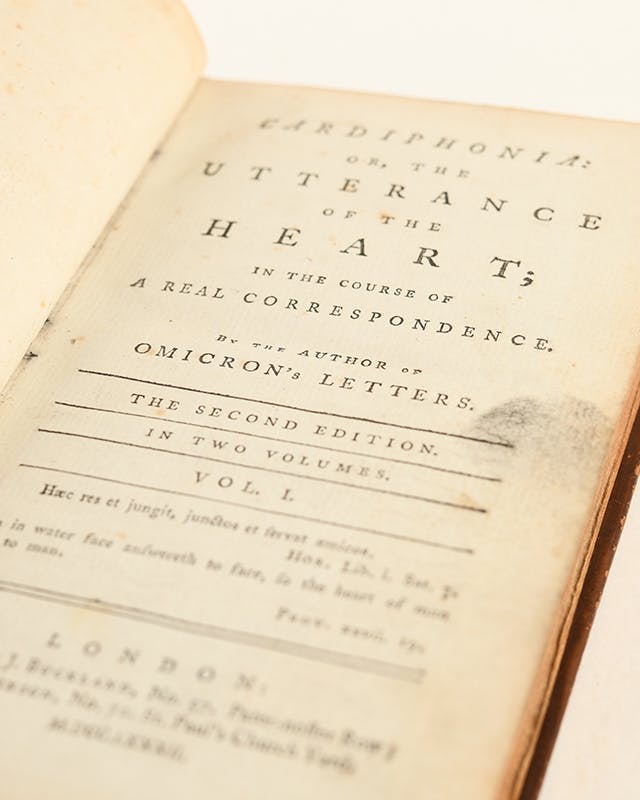

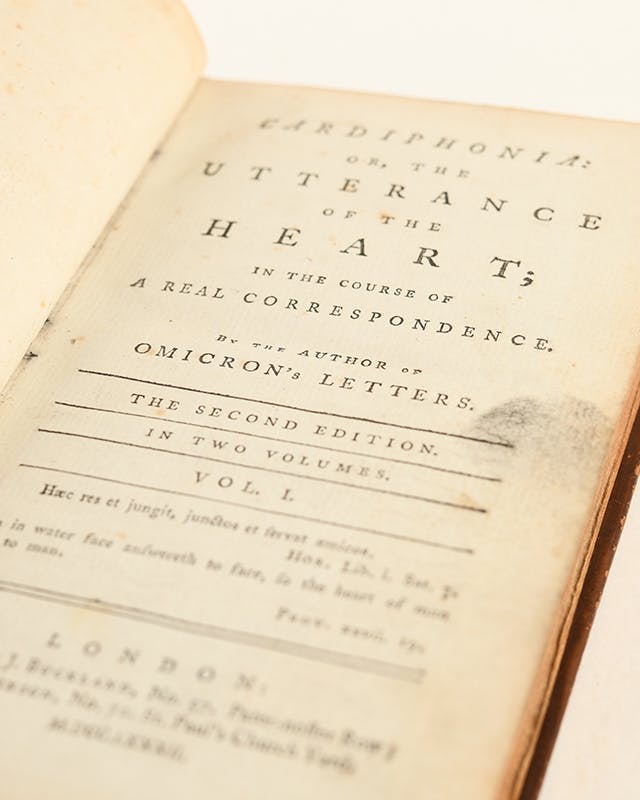

John Newton, Cardiphonia: Or, the Utterance of the Heart; In the course of a real correspondence, Volume 1

Printed for J. Johnson and Co., St. Paul’s Churchyard

London (England)

1782

PBK.006265.1–.2

Originally published in 1781 in two volumes, Cardiphonia is now a standard textbook for many students considering pastoral ministry. The first 26 letters were addressed to Lord Dartmouth, who recommended Newton for the parish at Olney.

Writing Amazing Grace

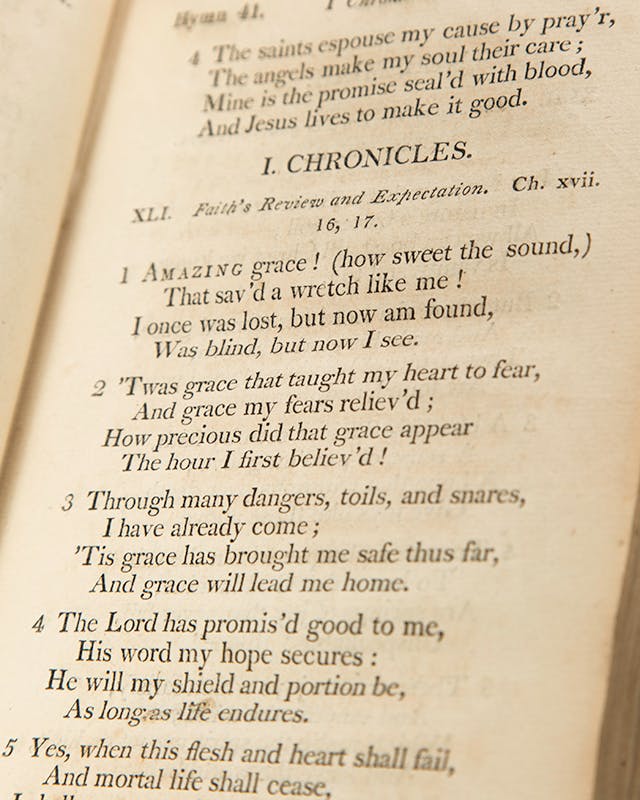

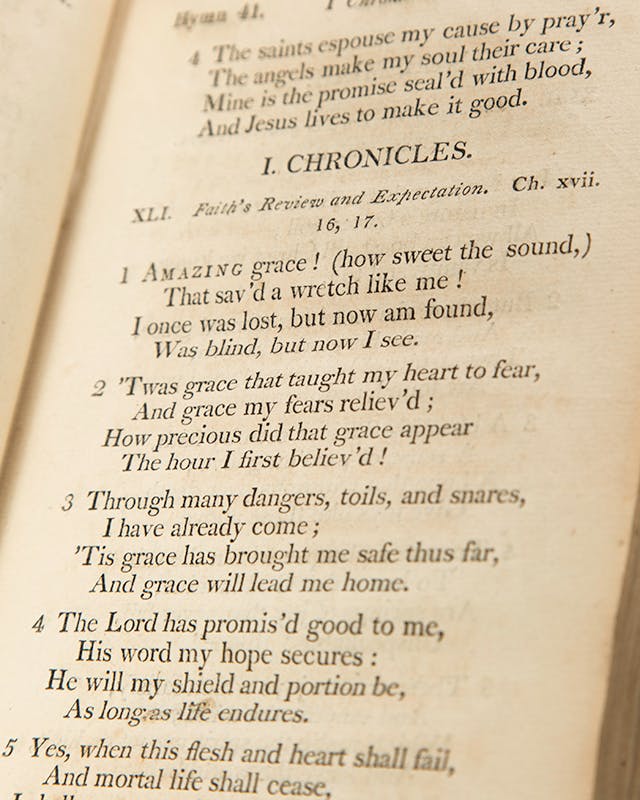

Newton wrote the lyrics for the yet unnamed “Amazing Grace” as a complement to his 1773 New Year’s Day sermon on 1 Chronicles 17:16–17 titled, “Faith’s Review and Expectations.” It was on this day in Lord Dartmouth’s Great Hall that Newton and his congregation first sang “Amazing Grace.”

In 1779, Newton and his friend William Cowper compiled a great number of their hymns together in a book titled, Olney Hymns. It contained 67 hymns written by Cowper and 281 written by Newton. This is where “Amazing Grace” first appears in print, as “Hymn XLI.”

John Newton and William Cowper, Olney Hymns

Printed and sold by W. Oliver, J. Buckland, and J. Johnson

London (England)

1779

PBK.00611.2

This is the first time the song “Amazing Grace” appears in print. No musical notation is present because it is not needed. Each hymn is written in one of several established meters. Tunes are interchangeable and titled independently.

The Later Years (1785–1807)

Toward the end of his life, Newton became increasingly engaged in politics, using his background as a reformed slave trader to make arguments against slavery. He publicly entered the discussion in 1788 with his book, Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade. One year later, William Wilberforce, a mentee of Newton’s, made his first speech to the House of Commons for the abolition of slavery, and in 1807, the year John Newton died, the Slave Trade Act was passed, banning the trade of enslaved people on British ships.

Newton’s legacy lives on in his most famous hymn, “Amazing Grace,” which became an anthem for the enslaved people of African descent as they struggled for reparation and equality in the years to come.

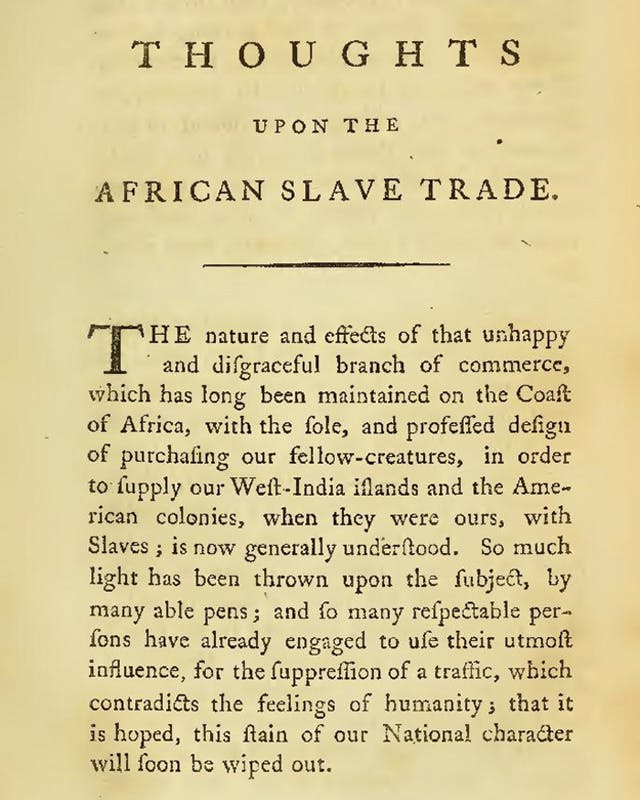

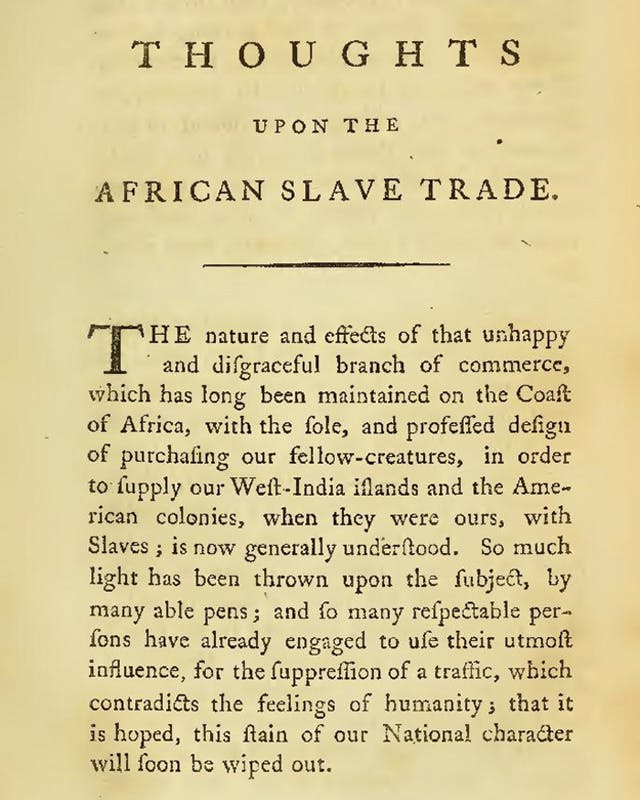

John Newton, Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade

England

1788

PBK.006008

Newton publicly entered the discussion regarding abolition with this published work. In it, he described the Middle Passage as a cramped and dangerous journey that did not allow the passengers enough room to stand, move, or even turn over without difficulty. He states, “They are kept down, by the weather, to breathe a hot and corrupted air, sometimes for a week: this, added to the galling of their irons, and the despondency which seizes their spirits when thus confined, soon becomes fatal.”